A century ago, physics breakthroughs came in rapid sequence. There was quantum mechanics and Einstein’s theories of space and time, lots of new particles, two new nuclear forces, and eventually the standard model of particle physics. This progress and its technological applications commanded respect, if not outright fear.

But today, the foundations of physics are a sleepy place. We’re still chewing on the same problems that we had a century ago—and all that chewing hasn’t made them any more digestible. What is dark matter? What does quantum mechanics really mean? And why does gravity refuse to cooperate with quantum physics? These are problems that, when I can’t sleep, I like to think have already kept Einstein up at night.

Since then, many ideas for solutions have been put forward for each of these problems, but it is rare for a truly new one to see the light of the day. This is why I was very excited to see the recent publications of Jonathan Oppenheim, a professor of quantum theory at University College London.

I have met Oppenheim a few times in the past because we share a similar intellectual history. Oppenheim and I both used to work on black holes, more specifically on the question of whether black holes truly destroy information. It seems that we both came to conclude the problem cannot be solved without first understanding how space, time, and quantum physics work together. But there, our ways parted. While I put the blame for the black hole information paradox on quantum physics, Oppenheim blamed gravity.

Read the rest of this article at: Nautilus

After Zac Brettler died, his parents struggled to decode the mystery of what had happened to him. They thought that they could pinpoint the moment he’d started to change: three years earlier, when, at sixteen, he began boarding at Mill Hill School, in North London. Zac had grown up in Maida Vale, a quietly affluent neighborhood in the city. His father, Matthew, is a director at a small financial-services firm; his mother, Rachelle, is a freelance journalist. As a child, Zac was bright and quirky, with curly red hair and a voice that was husky and surprisingly deep. He was an excellent mimic, and often entertained his parents and his brother, Joe, by putting on accents. Joe was nearly two years older than Zac, and he attended University College School, an élite day school in Hampstead. But when Zac took the University College entrance exam he struggled with the math portion, and wasn’t admitted. He was clearly intelligent and creative, but he was less of a student than Joe, and after applying unsuccessfully to two other schools he enrolled at Mill Hill, as a day student, at the age of thirteen.

Established in 1807 and occupying a rambling hundred-and-fifty-acre campus, Mill Hill has a hefty tuition price, but it has a less academic reputation than its peers. In the bourgeois milieu in which Zac grew up, to mention that you attended Mill Hill could be interpreted to mean that you’d been rejected by more rigorous schools. When Zac arrived, in 2013, he found himself in the company of the cosseted offspring of plutocrats from Russia, Kazakhstan, and China. “It was the children of oligarchs,” Andrei Lejonvarn, a former student who befriended Zac at Mill Hill, recalled. The kids wore designer clothes and partied at swank hotels. On cold days, rather than make the eight-minute walk from the dormitory to class, they summoned Ubers. Because London is a second home to so many rich people from abroad, the city has long been a bastion of gaudy consumerism. To Zac, his classmates’ ostentatiousness seemed exotic; his parents weren’t especially materialistic. Rachelle told me, “This world of Porsches and cosmetic surgery and Ibiza, it’s everything we’re not.” Once, an administrator called the Brettlers’ home to say that Zac had just left school in a chauffeured limousine. Zac confessed to his parents that he’d paid for this extravagance himself. “I wanted to see what it would feel like,” he said.

The commute from Maida Vale to Mill Hill took nearly an hour, so Zac began boarding during the week. To his parents, he seemed relatively well adjusted. He got decent grades and excelled at tennis and cricket. Occasionally, he brought friends home, and they appeared to be nice kids. But Zac was becoming more fixated on wealth. He’d been interested in cars since childhood, and now expressed embarrassment at his family’s humble Mazda. Like many adolescent boys, he developed a fascination with gangsters, watching documentaries about figures from the London underworld, among them the homicidal twins Reginald and Ronald Kray. He loved movies about guys on the make, such as “The Wolf of Wall Street” and “War Dogs,” which tells the true story of two young men in Florida who became international arms dealers.

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

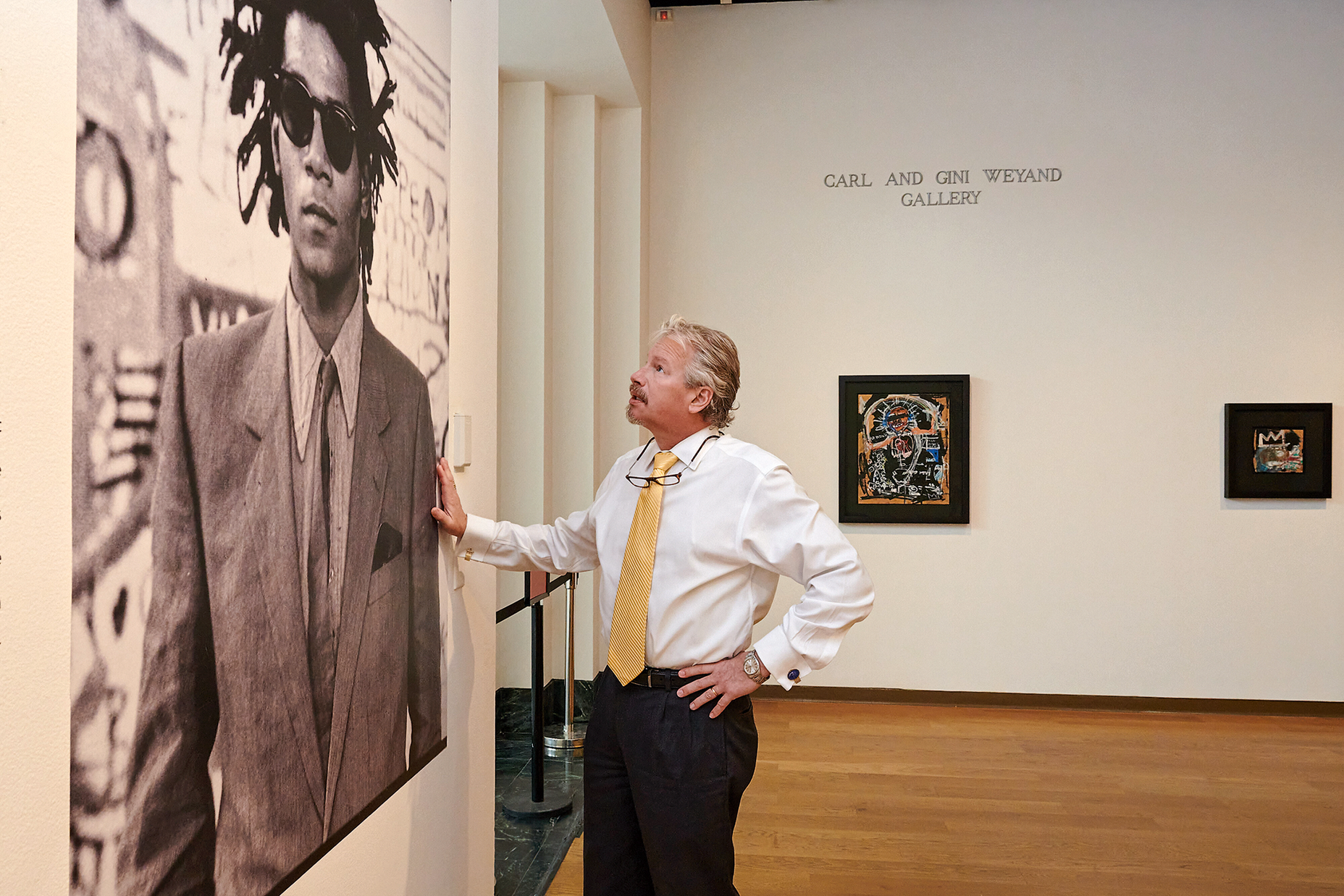

The paintings that appeared on eBay in the fall of 2012 featured skeletal figures with frenzied eyes, blocky crowns, and gnashing rows of teeth. They were done in brilliant blues and electric reds, mostly on scraps of cardboard that ranged from notebook-size to as big as a kitchen table. According to the man who was selling them—a professional auctioneer named Michael Barzman—he’d found them in a storage unit whose contents he’d bought after its renter had fallen behind on his bills. Barzman claimed he’d tossed the art in the trash. Then he’d fished it out and put it online.

Various deal-hunters who saw Barzman’s pieces were impressed by their resemblance to work by Jean-Michel Basquiat, an artist known for his energetic paintings of skull-like faces and expressionistic figures whose art grew only more celebrated after he died from a drug overdose in 1988, at age 27. Within a few months, the cardboards were snapped up by collectors who, intrigued by what they had, threw themselves into establishing who’d made them.

Read the rest of this article at: The Atlantic

The Combin de Valsorey is a rocky Alpine peak that stands nearly 4,200 metres above sea level near the Swiss-Italian border. Its north-west face rises 670 metres, at a gradient of about 50 degrees, steep enough that you can stand on the slope and touch the higher ground beside you without bending down.

In May 2016, when Jérémie Heitz climbed the Combin for the first time, the north-west face of the mountain looked like a vertical curtain of white, fringed by bands of dark rock. In several places, smears of greyish ice darkened the snow cover. Heitz’s ascent was nothing extraordinary in mountaineering terms: this face was first ascended in 1958, by Egbert Eigher and Erich Vanis. But Heitz was not climbing the Combin because he cared about going up – his plan was to ski down it.

Heitz, who was 26 at the time, is a professional freerider, a skier who spends his time on wild mountain slopes far from groomed pistes and resort boundaries. His speciality lies at the extreme end of freeriding: steep skiing, descending ground with a gradient twice that of some “expert” terrain in ski resorts. This activity combines two of the world’s most perilous sports – alpine mountaineering and backcountry skiing – and regularly kills a handful of its practitioners every year. Heitz had come to the Combin as part of a film project he had devised, called La Liste, which involved descending some of the steepest and tallest faces in the western Alps.

Heitz would not be the first person to ski the north-west face of the Combin; that accomplishment was secured in 1981. But the pioneers of steep skiing, who developed the sport in the 1960s and 70s, had relied on so-called pedal-hop turns, making one staccato leap after another to deal with the impossibly precipitous slopes. Heitz had a different vision.

In its early days, steep skiing’s drama had come from the fact that these slopes could be skied at all. Now Heitz sought to bring speed – up to 75mph (120km/h) – and style to a sport that once impressed through sheer audacity. The result was something remarkable – and even riskier than before. “That style of skiing is incredibly dangerous,” says Dave Searle, a British mountain guide based in Chamonix. “You can keep pushing the limits of it until you either stop pushing the limits, or you die. That’s the two things really.”

Read the rest of this article at: The Guardian

Last week, having tried and failed to kill him with the more traditional lethal injection, the state of Alabama suffocated Kenneth Smith to death for his role in a 1988 murder-for-hire. In this unprecedented method, which the state has called “nitrogen hypoxia”, the victim is forced to inhale pure nitrogen, depriving them of oxygen until they are dead. Though this technique was sold as a more humane form of execution, “nitrogen hypoxia” happens to be a bullshit, made-up term used to lend a veneer of scientific legitimacy to a barbaric style of state-sanctioned murder. Smith shook and spasmed in the 15 minutes before he died, appearing to witnesses to be in considerable pain.

Pragmatically, the case against the death penalty is impregnable. Hundreds of people on death row in the United States have been exonerated in the past 50 years alone, demonstrating the serial incompetence of our criminal justice system. There is no way to evaluate how many innocent people have been put to death, though there are dozens of cases where we now know that someone who was executed was probably innocent. You may dip back into history or stick to contemporary examples. Italian immigrants and anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti were put to death in 1927 for robbery and murder despite another man having confessed to the crime, and were only officially exonerated more than half a century later. One of many more recent cases of likely wrongful execution occurred in 2004, when Cameron Todd Willingham, a Texas man accused of setting a fire that killed his three children, was administered a lethal injection, despite very shaky evidence of his guilt. The testimony of the fire marshal involved was comically unscientific and unreliable, but Texas governor Rick Perry appeared to manoeuvre behind the scenes to make sure Willingham was executed, in need of the political bump that (perversely) accompanies any use of the death penalty in Texas. Then there are those, like Anthony Apanovitch, who essentially everyone admits are innocent, but whom the legal system refuses to free from death row.

Read the rest of this article at: Unheard