There are certain images that slither past good taste and politics and sink their teeth straight into the subconscious. For instance: a man dressed in a tuxedo and a Ronald Reagan mask, using a gasoline pump as a flamethrower. He is torching his getaway vehicle and taking his time; the scene isn’t shot in slow motion, but I always remember it that way. In about thirty seconds, a cop will tackle him, prompting a long foot chase, but for now he waves his weapon like a kid with a sparkler on New Year’s Eve. We can’t see his expression, but Reagan’s face is grinning, and I’d like to imagine that the face underneath is, too. Don’t all bad guys dream of being children again?

The masked man is Patrick Swayze, the cop is Keanu Reeves, the woman who has sicced one on the other is the director Kathryn Bigelow, and the thing that binds them all together is “Point Break.” Those of us who love the film, which is showing in a new restoration, at Metrograph, talk about it in much the same way that others talk about “Showgirls”—i.e., as what used to be called a cult movie, before it became clear that there are only cults of varying sizes. It was released in 1991, the year of “Nevermind” and Desert Storm, though you could also think of it as the era when everyone in Hollywood movies looked slightly wet—appropriate here, since “Point Break” is about surfing. Also law enforcement and skydiving.

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

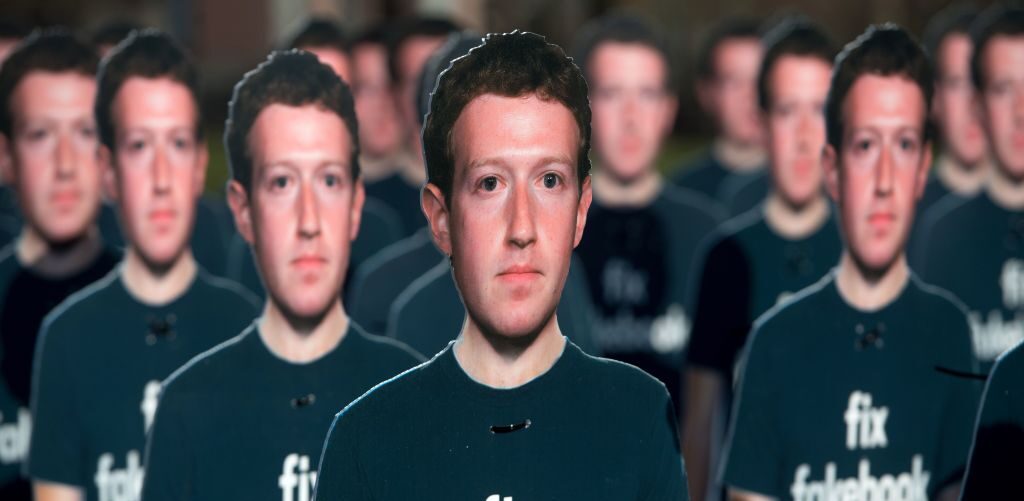

How will Facebook celebrate its 20th birthday? Perhaps it will create one of those cute video montages they like to generate at significant moments. Starting with a tinkling piano soundtrack, a couple of breathless friend requests, and some self-conscious, tentative writing of “hello!” on other users’ walls, it might then pass quickly through moments of chronic oversharing, passive-aggressive, stalking of exes, and horrified untagging of yourself in unflattering photos. Next, it might linger briefly on a few memes, embarrassing jokes, and ice-bucket challenges; and then arrive with a soaring crescendo and a lot of air-punching at Facebook’s supposedly beneficial role in the Arab Spring and the #MeToo movements.

Wholly absent from the narrative, one assumes, would be allegations of data harvesting, electoral manipulation, politicised shadow-banning, hosting of terrorist footage, the exacerbation of ethnic and religious conflicts, and the significant worsening of mental health in adolescent girls. Nor, I suspect, would any celebratory montage feature this week’s congressional hearing on online child exploitation, during which a senator dramatically told founder Mark Zuckerberg “you have blood on your hands”. Last year, a Guardian investigation revealed that, despite historic efforts to stop it, Facebook is still a major site of child sex trafficking. Meanwhile Wall Street Journal investigators have separately revealed that the platform is building “communities devoted to child sexualisation” (surely the final nail in the coffin for misty-eyed uses of the word “community”). Attention-hungry algorithms are apparently identifying users interested in paedophilic content and pointing them towards more of the same; connecting those with an initial interest in pictures of young cheerleaders and gymnasts, and then making suggestions for more hardcore image sites and private groups.

Such an inglorious future could not have been foretold during Facebook’s birth on the Harvard campus in 2004 — and nor even was it evident in 2008, when the platform really started to take off. Controversial algorithmic changes were still in the company’s future, and had yet to unleash their epistemic and moral carnage. But it was at least clear from an early stage that something momentously compulsive was now upon us, and that there would be no going back. Henceforth, the population would be divided into two groups: those of us wandering around the world with immediate access to a real-time digital soap opera, in which we too could perform as characters if we liked; and those few souls who remained blissfully unaware and unaffected.

Read the rest of this article at: Unheard

When Rachael Kay Albers was shopping around her book proposal, the editors at a Big Five publishing house loved the idea. The problem came from the marketing department, which had an issue: She didn’t have a big enough following. With any book, but especially nonfiction ones, publishers want a guarantee that a writer comes with a built-in audience of people who already read and support their work and, crucially, will fork over $27 — a typical price for a new hardcover book — when it debuts.

It was ironic, considering her proposal was about what the age of the “personal brand” is doing to our humanity. Albers, 39, is an expert in what she calls the “online business industrial complex,” the network of hucksters vying for your attention and money by selling you courses and coaching on how to get rich online. She’s talking about the hustle bro “gurus” flaunting rented Lamborghinis and promoting shady “passive income” schemes, yes, but she’s also talking about the bizarre fact that her “65-year-old mom, who’s an accountant, is being encouraged by her company to post on LinkedIn to ‘build [her] brand.’”

Read the rest of this article at: Vox

When Molly Crabapple touched down in Italy last year for the International Journalism Festival, she expected the usual. The annual conference bills itself as Europe’s largest media event, and Crabapple had planned to give a talk about her career as an artist and writer reporting from the front lines of conflict zones. But as she took in some of the panels, she felt herself growing uneasy.

Sprinkled among the journalists discussing topics such as the war in Ukraine and the state of podcasting, some of the speakers were promoting the use of generative AI. She overheard someone say that journalists write too much, that much of their work could be automated. “I was like, this is disgusting,” she told me. “Why isn’t anyone going to challenge this?” When it came time for her own panel, she decided to do just that, saying onstage, “The use of generative AI is not only going to destroy my industry—it is going to destroy all of yours, if you’re anyone who creates anything … If you’re anyone here who creates, it is in your interest to fight these generative-AI platforms.”

Crabapple then released an open letter with the Center for Artistic Inquiry and Reporting, calling on publishers to ban generative AI from replacing human art and writing in their operations. Nearly 4,000 signatories added their name over the course of the year, including the MSNBC host Chris Hayes, the author Naomi Klein, and the actor John Cusack. But though Crabapple has found her supporters, she noted a particular kind of backlash as well: “Anyone who is critical of the tech industry always has someone yell at them ‘Luddite! Luddite!’ and I was no exception,” she told me. It was meant as an insult, but Crabapple embraced the term. Like many others, she came to self-identify as part of a new generation of Luddites. “Tech is not supposed to be a master tool to colonize every aspect of our being. We need to reevaluate how it serves us.”

Read the rest of this article at: The Atlantic

There has never been a worse time to be a UFO skeptic. Last month, Sean Kirkpatrick, the head of the Pentagon office responsible for investigating unexplained aerial events, stepped down. He said he was tired of being harassed and accused of hiding evidence, and he lamented an erosion in “our capacity for rational, evidence-based critical thinking.”

He may have been pushed over the edge by a pair of events from the past summer. In June of last year, Avi Loeb, an astronomer at Harvard, announced that he had found some tiny blobs of metal by dragging a magnetic sled over the bottom of the Pacific near Papua New Guinea. He claimed that these blobs were metallic droplets that had melted off an interstellar object that might have been “a technological gadget with artificial intelligence” — the product of beings from another star system.

In July, David Grusch, a former intelligence officer, stepped out of the shadows to announce that the U.S. military Establishment currently possesses a small fleet of nonhuman pre-owned flying saucers. He didn’t call them saucers; he called them UAPs, or “unidentified anomalous phenomena,” which used to be called UFOs. But basically, we’re talking saucers.

Grusch’s story first reached the public via a journalist named Leslie Kean (pronounced Kane), who had co-written a hugely influential article about UFOs that appeared on the front page of the New York Times in 2017. She and Helene Cooper, a Pentagon correspondent for the paper, along with a writer named Ralph Blumenthal, revealed that Senator Harry Reid had gotten the Pentagon to create a secret, “mysterious” $22 million program to study UFOs. A few years later, Kean was the subject of a long profile in The New Yorker by staff writer Gideon Lewis-Kraus with the web title “How the Pentagon Started Taking U.F.O.s Seriously.”

Thoughtful, sensible-seeming, non-crankish people at Harvard, at The New Yorker, at the New York Times, and at the Pentagon seemed to be drifting ever closer to the conclusion that alien spaceships had visited Earth. Everyone was being appallingly open-minded. Yet even after more than 70 years of claimed sightings, there was simply no good evidence. In an age of ubiquitous cameras and fancy scopes, there was no footage that wasn’t blurry and jumpy and taken from far away. There was just this guy Grusch telling the world that the government had a “crash-retrieval and reverse-engineering program” for flying saucers that was totally supersecret and that only people in the program knew about the program. Grusch said he had learned about it while serving on a UAP task force at the Pentagon. He interviewed more than 40 people, and they told him wild things. He said he couldn’t reveal the names of the people he interviewed. He shared no firsthand information and showed no photos. He said the program went back decades, back to the saucer crash that happened in Roswell, New Mexico.

Read the rest of this article at: New York Magazine

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/73103019/Vox_EleniKalorkoti.0.jpg)