A person can live in many places but can settle in only one. You may not understand the difference until you’ve found the city or the town or the patch of countryside that sounds a distinct internal chord. For much of my life, I was on the move. I grew up in Texas, in Abilene and Dallas, but as soon as the gate opened I fled the sterile culture, the retrograde politics, the absence of natural beauty. I met my wife, Roberta, in New Orleans. She was also on the run, from the racism and suffocating conformity of Mobile, Alabama. In our married life, we have lived in Cambridge, Massachusetts; Cairo, Egypt; Quitman, Texas; Durham, North Carolina; Nashville; and Atlanta—all desirable places with much to recommend. We travelled the world. I have spent stretches of my professional life in the places you would expect—New York, Los Angeles, and Washington, D.C., all cities that I revere, but not places we chose to settle.

Unconsciously, during those vagabond years, we were on the lookout for home. I nursed a conception of an ideal community, one that combined qualities I loved about other places: the physical beauty, say, of Atlanta; the joyful music-making of New Orleans; an intellectual scene fed by an important university, as in Cambridge or Durham; a place with a healthy energy and ready access to nature, such as Denver or Seattle; a spot where we could comfortably find friends and safely raise children. I’m not saying that we couldn’t have been happy in any of the places I’ve mentioned, but something kept us from profoundly identifying with them.

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

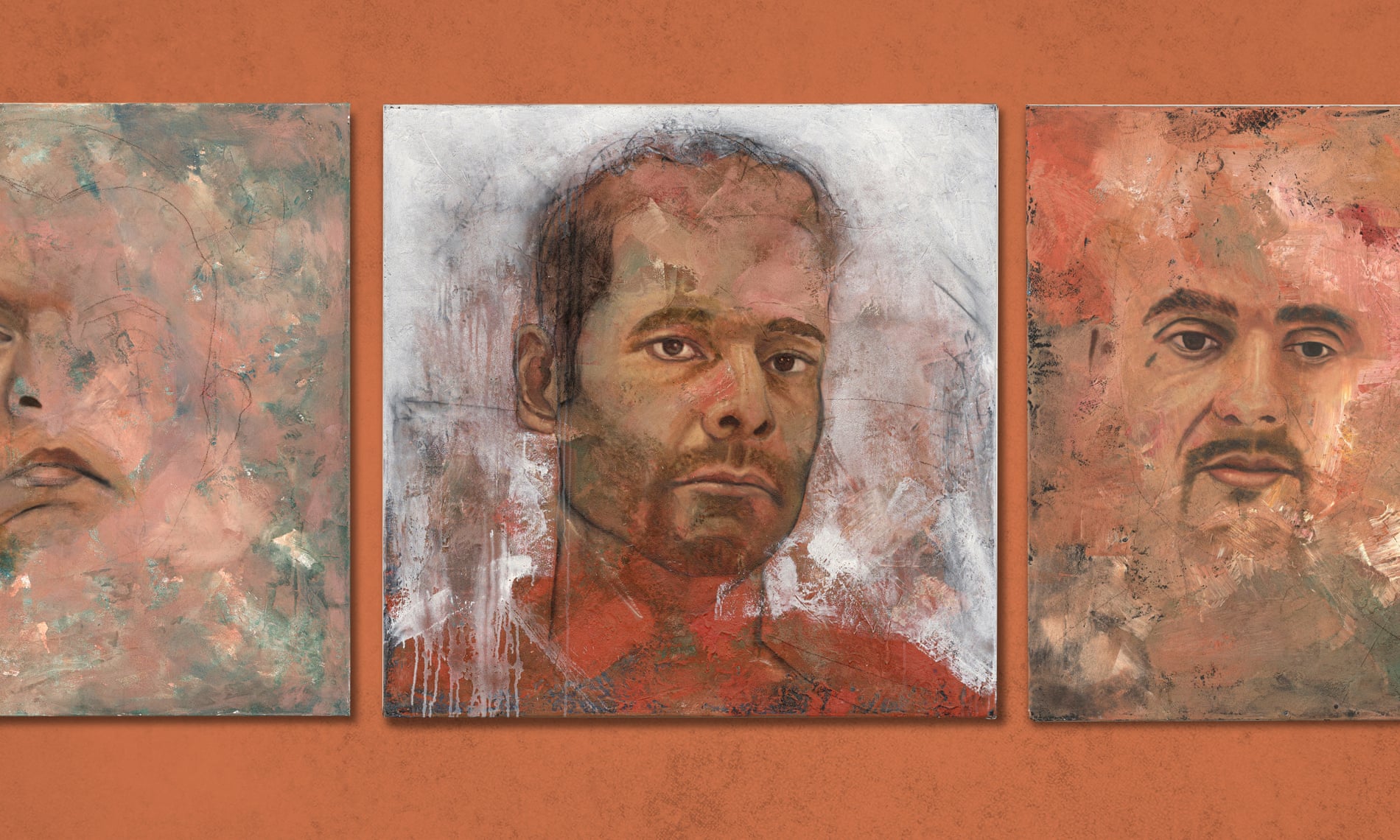

After two decades working in some of Mexico’s toughest prisons, warden Ángeles Zavala thought she had seen it all. Then one morning in 2016, she arrived for work at Puente Grande prison to find a local artist waiting for her. The man had recently completed a few workshops with inmates in another part of the prison, and had a proposal. Speaking in rapid-fire bursts, the artist told Ángeles he wanted to move into the maximum-security prison and live there for six weeks, in order to teach some of the country’s most dangerous inmates how to paint. Through art therapy, he would help them change their lives. And he wanted to start with the veteran narcos of Mexico’s violent drug war.

“I was thinking: ‘What is wrong with him?’” Ángeles said later. “‘Everyone is trying to get out and César wants to live here?’”

César Aréchiga, then 36, had achieved a mild degree of regional renown for his realist paintings the size of barn doors. He was a bear of a man, but with his artistic verve, clear-framed glasses and pack-a-day smoking habit, he seemed more at home in Guadalajara’s trendy coffee shops than in a prison full of gang members. Ángeles was intrigued. There are almost no art programmes for Mexican prisoners; few people are brave enough to teach inside the prisons. If César was crazy enough to try, why not see what might happen?

Read the rest of this article at: The Guardian

You can probably think of at least one building you have visited that felt as though it reached inside you, affected you deeply, and perhaps changed the way that you thought about the world. For me, my first visit to St Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City when I was in my 30s had this impact. The sheer size of its interior knocked the wind out of me, though the details were just as significant. Every surface seemed covered with exquisitely detailed art – material evidence of the immense human effort over many centuries that had produced this setting. As I surveyed my surroundings with tottering knees, I realised how far the effects of architecture could go beyond utilitarian functions like keeping us out of the rain.

But it doesn’t take a massive cathedral to ignite interest in the human response to buildings. You might have experienced similar feelings in many different kinds of settings. Small churches, college courtyards, commercial headquarters (think of the main office of a major bank) can all evoke a response. Even everyday architectural spaces can connect with our feelings. Think of when you last walked into someone’s home for the first time and experienced an ephemeral sense of its atmosphere. Architects have written entire books about these feelings.

Read the rest of this article at: Psyche

The classroom is quiet. It’s a Friday afternoon in the first week of a new quarter. The threat of a midterm exam is far off, and all we really want to do is go home and enjoy the weekend.

Dr. Miller stands at the bottom of the classroom. (Names in this piece have been changed.) He’s waiting for the clock to strike the hour. I say bottom because third-year veterinary medicine students have lectures in a classroom designed like the nosebleed section of a stadium. Someone once told me it’s the steepest classroom in North America. I’m not sure if that’s true, but it always gets a laugh at vet conferences.

Miller is tall and balding, with ears that jut out from his head. He dresses in the classic uniform of Midwestern academia: khakis, dock shoes, plaid short-sleeved button-down, thick leather belt. We know the look well: My classmates and I have been through a grinder of a program, literally hundreds of hours spent studying or in class together. But despite our obvious comfort with one another, the room is dead quiet. Why?

It might have something to do with the title slide that Miller has just projected: Euthanasia and its many forms: on farm and at home.

We all know that this lecture will be grim—Miller is a pig vet, after all. That might mean nothing to you, but in the vet world, it says everything. Swine vets work on swine systems and whole populations. They treat groups of animals, not individuals the way general-practice vets do. Doing so requires an incredible amount of data, and the ability to interpret it dispassionately.

Read the rest of this article at: Slate

The ways we socialize and date, commute and work are nearly unrecognizable from what they were three years ago. We’ve enjoyed a global pandemic, open employer-employee warfare, a multifront culture war, and social upheavals both great and small. The old conventions are out (we don’t whisper the word cancer or let women off the elevator first anymore, for starters). The venues in which we can make fools of ourselves (group chats, Grindr messages, Slack rooms public and private) are multiplying, and each has its own rules of conduct. And everyone’s just kind of rusty. Our social graces have atrophied.

We wanted to help. So we started with the problems — not the obvious stuff, like whether it’s okay to wear a backpack on the subway or talk loudly on speakerphone in a restaurant (you know the answers there). We asked people instead what specific kinds of interactions or situations really made them anxious, afraid, uncertain, ashamed. From there, we created rigid, but not entirely inflexible, rules.

Then we took our own medicine — we implemented these rules in our professional and personal lives. Some really didn’t work. (“It’s been great to chat” didn’t quite land when we used it as a way to exit a boring conversation at a holiday party.) Others felt like instant canon (we agreed, for example, that text-message amnesty is granted after 72 hours). We fine-tuned and eliminated. We talked to friends, entertaining experts, and service workers. We sparked office arguments and made messes and ended up with a guide that we hope will stand the test of at least a bit of time — until the next great exciting social upheaval.

Read the rest of this article at: The Cut