Anyone who’s worked for a major book publisher in recent memory knows the energy that crackles through the office at 4:59 P.M. on Wednesday afternoons, right before the preview of next week’s best seller list arrives from The New York Times. After months of pitching reviews, planning marketing campaigns, doing bookseller outreach, and begging for budget, this is the moment when you find out if it was enough to earn your author a spot on the best seller list.

The New York Times best-seller list debuted in October 1931, reporting first on the top-selling titles in New York City before expanding in 1942. Over the years, what’s known in the industry as “the list” has come to comprise eleven weekly and seven monthly lists, covering paperbacks, audiobooks, and e-books (combined with print sales), as well as separate lists for children’s books, business titles, and more.

No one outside The New York Times knows exactly how its best sellers are calculated—and the list of theories is longer than the actual list of best sellers. In The New York Times’ own words, “The weekly book lists are determined by sales numbers.” It adds that this data “reflects the previous week’s Sunday-to-Saturday sales period” and takes into account “numbers on millions of titles each week from tens of thousands of storefronts and online retailers as well as specialty and independent bookstores.” The paper keeps its sources confidential, it argues, “to circumvent potential pressure on the booksellers and prevent people from trying to game their way onto the lists.” Its expressed goal is for “the lists to reflect what individual consumers are buying across the country instead of what is being bought in bulk by individuals or associated groups.” But beyond these disclosures, the Times is not exactly forthcoming about how the sausage gets made.

Laura B. McGrath, an assistant professor of English at Temple University who teaches a course on the history of the best seller, compares The New York Times’ list to the original recipe for Coca-Cola: “We have a pretty good idea of what goes into it, but not the exact amount of each ingredient.”

Read the rest of this article at: Esquire

Squinting through sterile overhead lighting, I scan the emergency room for traces of red and green. I listen closely for the jingling of bells and the croon of Bing Crosby. I’m relieved to detect nothing, just injured people groaning, which by this point in December — the 22nd — is practically soothing. Lying flat on my back in a hospital bed, covered in sap and bleeding out of my forehead, I don’t feel very Christmasy. I feel concussed.

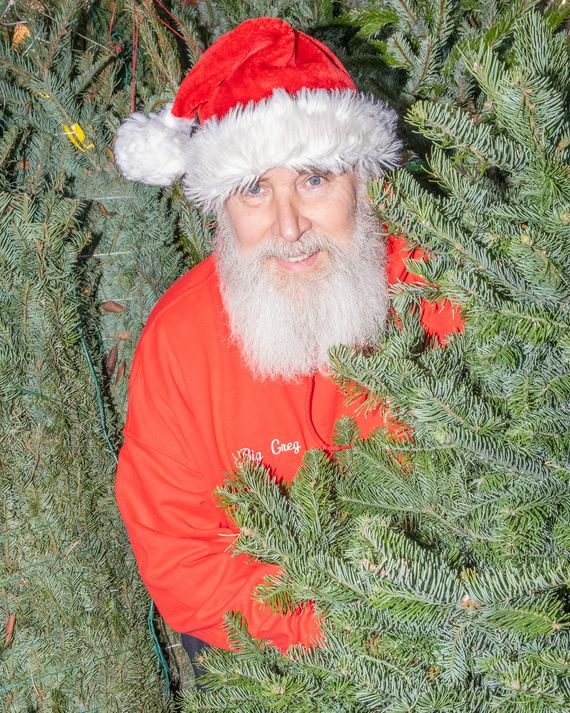

Even still, I can’t help but think about Christmas, the holiday that has been my daily reality for two years. I’ve worked spring, summer, fall, and winter for Santa Claus — or, rather, for a man who looks exactly like Santa Claus, and possibly thinks he is Santa Claus, and is, fittingly, one of the top sellers of Christmas trees in New York City.

Christmas trees are big business in New York. A lot of people see the quaint plywood shacks that appear on sidewalks just before Thanksgiving, each with its own tiny forest of evergreens, and they imagine that every one is independently owned, maybe by jolly families of lumberjacks looking to make a few holiday bucks. That’s what I thought, anyway. In reality, a few eccentric, obsessed, sometimes ruthless tycoons control the sale of almost every single tree in the city. They call themselves “tree men,” and they spend 11 months a year preparing for Christmastime — which, to them, is a blistering 30-day sprint to grab as much cash as they can.

I learned early on that they’ve carved up the city into territories, that the same Christmas tree can sell for four times as much in Soho as in Staten Island and that turf wars aren’t uncommon. These days, lower Manhattan is tentatively shared by three former collaborators: Billy Calvoni and his two embittered ex-protégés, George Smith and Heather Neville. Calvoni is a former fruit peddler and current real-estate investor said to have purchased 400 houses in Arizona. Smith is a part-time carnival operator who once served time for impersonating a police officer during a robbery. Neville is consistently underestimated and intermittently merciless. Smith and Neville cut ties with Calvoni because of problems with his late partner, Scott Lechner, a.k.a. Willie the Hat, a diminutive man known for wearing fedoras and sharkskin gloves because sharkskin is the only material thin enough to count cash with.

Uptown is split two ways between George Nash and Kevin Hammer, former partners, recent enemies, and currently cautious friends. Nash, who sells to much of Harlem, is a smooth-talking old hippie from Vermont. Hammer is a Brooklyn-born Scientologist and the éminence grise of Christmas trees, by far the most powerful force in the business. He is largely responsible for shaping the market into the oligopoly it is today, and at the peak of his powers, Hammer was rumored to own nearly half the tree stands in Manhattan, bringing in more than $1 million each December. According to lore, Hammer lives on a yacht somewhere in the Atlantic, visiting New York only at Christmastime, when he holes up in a midtown hotel room, a pile of cash on the bed and one pit bull squatting on either side of him.

Read the rest of this article at: Curbed

When you and I look at the same object we assume that we’ll both see the same color. Whatever our identities or ideologies, we believe our realities meet at the most basic level of perception. But in 2015, a viral internet phenomenon tore this assumption asunder. The incident was known simply as “The Dress.”

For the uninitiated: a photograph of a dress appeared on the internet, and people disagreed about its color. Some saw it as white and gold; others saw it as blue and black. For a time, it was all anyone online could talk about.

Eventually, vision scientists figured out what was happening. It wasn’t our computer screens or our eyes. It was the mental calculations that brains make when we see. Some people unconsciously inferred that the dress was in direct light and mentally subtracted yellow from the image, so they saw blue and black stripes. Others saw it as being in shadow, where bluish light dominates. Their brains mentally subtracted blue from the image, and came up with a white and gold dress.

Not only does thinking filter reality; it constructs it, inferring an outside world from ambiguous input. In Being You, Anil Seth, a neuroscientist at the University of Sussex, relates his explanation for how the “inner universe of subjective experience relates to, and can be explained in terms of, biological and physical processes unfolding in brains and bodies.” He contends that “experiences of being you, or of being me, emerge from the way the brain predicts and controls the internal state of the body.”

Prediction has come into vogue in academic circles in recent years. Seth and the philosopher Andy Clark, a colleague at Sussex, refer to predictions made by the brain as “controlled hallucinations.” The idea is that the brain is always constructing models of the world to explain and predict incoming information; it updates these models when prediction and the experience we get from our sensory inputs diverge.

Read the rest of this article at: MIT Technology Review

ZÜRICH — In the aftermath of World War II, the leaders of Switzerland decided that the country needed to urgently modernize, and concluded that a remote and picturesque valley high in the Alps could be developed for hydropower. Nearly 350 square miles of snow and ice covered the mountains there, and much of it turned to liquid in the spring and summer, a force of water that, if harnessed correctly, could turn turbines and create electricity. And so a plan was hatched to conquer this “white coal” by building the tallest concrete gravity dam the world had ever seen: the Grande Dixence. At nearly 1,000 feet high, it’d surpass the Hoover Dam and be only slightly shorter than the Empire State Building, then the tallest building in the world.

From 1951 onwards, around 3,000 geologists, hydrologists, surveyors, guides and laborers, outfitted with an assemblage of trucks, diggers, dumpsters and drills, advanced like an army into a mostly untouched area of the Alps. To paraphrase Leo Marx: The machines had entered the garden.

Up there, the workers were met with freezing temperatures that seared the chest and burst the lips, a blazing sun that burned the skin, and a constant threat of avalanches. They lacked waterproof clothing and lived in makeshift shacks, at least until social services forced the construction of an accommodation block that they nicknamed “the Ritz.” The fine dust of pulverized rock coated their lungs, developing, for some, into a slow and deadly disease called silicosis. The site had its own chaplain, Pastor Pache, who was available to counsel the men about their confrontations with nature and death.

Ultimately, the job these men performed, more than anything else, was pouring concrete, and at a nearly unimaginable scale: more than 200 million cubic feet of it, just about enough to build a wall five feet high and four inches wide around the equator. Cableways carried an endless procession of 880-pound buckets of cement (a primary ingredient in concrete alongside sand, gravel and water) up and down the mountains at a pace of 220 tons each hour.

For more than a decade, through snow and rain and fog, the workers poured that thick grey mixture day after day after day, and gradually a monolith began to rise between the mountains.

One of the workers was 23-year-old Jean-Luc Godard, who would go on to become one of the most influential filmmakers in the modern era. After sweet-talking his way into a cushy job as a telephone operator, he borrowed a camera and began capturing images of the never-ending flow of concrete. In the film he eventually made (not one of his finest), workers were portrayed like little ants alongside grand machines, and a triumphant soundtrack of classical music played beneath a cheerful voiceover that celebrated the national importance of this monumental construction. Opération Béton, he named it — Operation Concrete — and the construction company bought it off him and rolled it out as an advertisement in cinemas across the nation.

“The modernist utopian dream that the speed and malleability of concrete might solve housing crises, revolutionize cities and birth new ways of living and being was already being shattered by a spiraling capitalist cycle of speculation, construction, deterioration and demolition.”

Read the rest of this article at: Noema