WHEN MY PARTNER and I first walked through the door of our prospective home, last October, the air was thick with a musty scent that I preferred not to place. It was clear that the carpet upstairs, which appeared to be the culprit, would have to go. Our feet creaked on the laminate as we descended into the unfinished basement. Previous residents had graffitied the exposed drywall with markers, pen, and chalk: “YOU MAKE A MESS, YOU CLEAN IT.” The faded letters looked like someone had once tried, hopelessly, to erase them.

But, still, there was something charming about the place. It was the type of house I always imagined would be my first: a small semi on a crescent of modest homes, tucked beneath old trees. It was a small-town Ontario home where a young couple could build the kind of life that, for my generation, always seemed tantalizingly out of reach—one with a house, a back yard, space for kids if we someday decide to have them.

Read the rest of this article at: The Walrus

On a damp and cloudy afternoon on February 15, 1894, a man walked through Greenwich Park in East London. His name was Martial Bourdin — French, 26 years of age, with slicked-back dark hair and a mustache. He wandered up the zigzagged path that led to the Royal Observatory, which just 10 years earlier had been established as the symbolic and scientific center of globally standardized clock time — Greenwich Mean Time — as well as the British Empire. In his left hand, Bourdin carried a bomb: a brown paper bag containing a metal case full of explosives. As he got closer to his target, he primed it with a bottle of sulfuric acid. But then, as he stood facing the Observatory, it exploded in his hands.

The detonation was sharp enough to get the attention of two workers inside. Rushing out, they saw a park warden and some schoolboys running towards a crouched figure on the ground. Bourdin was moaning and screaming, his legs were shattered, one arm was blown off and there was a hole in his stomach. He said nothing about his identity or his motives as he was carried to a nearby hospital, where he died 30 minutes later.

Nobody knows for sure what Bourdin was trying to do that day. An investigation showed that he was closely linked to anarchist groups. Numerous theories circulated: that he was testing the bomb in the park for a future attack on a public place or was delivering it to someone else. But because he had primed the device and was walking the zigzagged path, many people — including the Home Office explosives expert, Vivian Dering Majendie, and the novelist Joseph Conrad, who loosely based his book “The Secret Agent” on the event — suspected that Bourdin had wanted to attack the Observatory.

Bourdin, so the story goes, was trying to bomb clock time, as a symbolic revolutionary act or under a naive pretense that it may actually disrupt the global measurement of time. He wasn’t the only one to attack clocks during this period: In Paris, rebels simultaneously destroyed public clocks across the city, and in Bombay, the famous Crawford Market clock was shattered with gunfire by protesters.

Around the world, people were angry about time.

Read the rest of this article at: Noema

In the summer of 2020, Daniel Beunza, a voluble Spanish social scientist who taught at Cass business school in London, organised a stream of video calls with a dozen senior bankers in the US and Europe. Beunza wanted to know how they had run a trading desk while working from home. Did finance require flesh-and-blood humans?

Beunza had studied bank trading floors for two decades, and had noticed a paradox. Digital technologies had entered finance in the late 20th century, pushing markets into cyberspace and enabling most financial work to be done outside the office – in theory. “For $1,400 a month you can have the [Bloomberg] machine at home. You can have the best information, all the data at your disposal,” Beunza was told in 2000 by the head of one Wall Street trading desk, whom he called “Bob”. But the digital revolution had not caused banks’ offices and trading rooms to disappear. “The tendency is the reverse,” Bob said. “Banks are building bigger and bigger trading rooms.”

Why? Beunza had spent years watching financiers like Bob to find the answer. Now, during lockdown, many executives and HR departments found themselves dealing with the same issue: what is gained and what is lost when everyone is working from home? But while most finance companies focused on immediate questions such as whether employees working remotely would have still access to information, feel part of a team and be able to communicate with colleagues, Beunza thought more attention should be paid to different kinds of questions: how do people act as groups? How do they use rituals and symbols to forge a common worldview? To address practical concerns about the costs and benefits of remote working, we first need to understand these deeper issues.

Office workers make decisions not just by using models and manuals or rational, sequential logic – but by pulling in information, as groups, from multiple sources. That is why the rituals, symbols and space matter. “What we do in offices is not usually what people think we do,” Beunza told me. “It is about how we navigate the world.” And these navigation practices are poorly understood by participants like financiers – especially in a digital age.

Read the rest of this article at: The Guardian

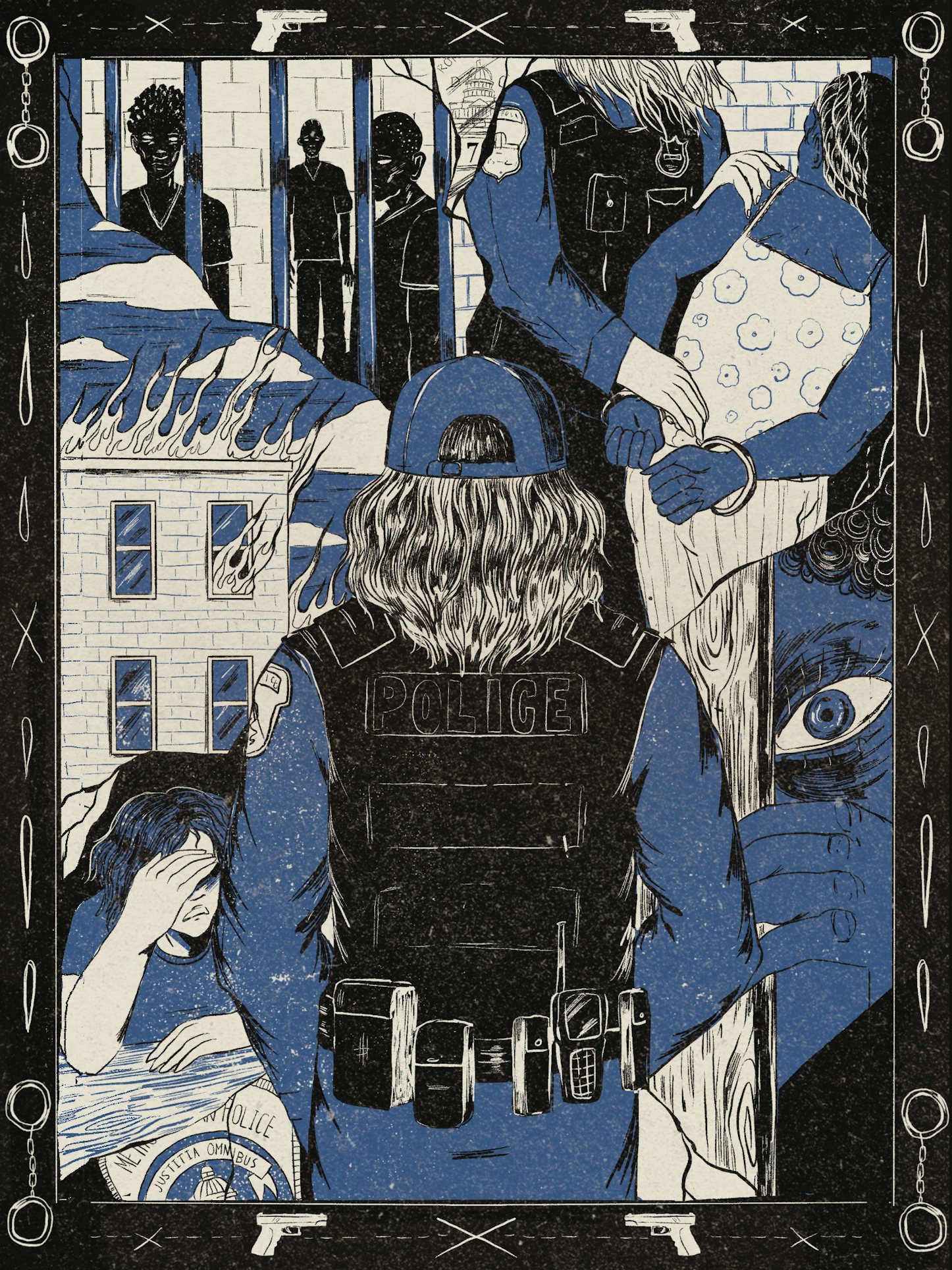

The Professor Who Became a Cop

For as long as there have been police, there have been bestselling police biographies and autobiographies. In nineteenth-century Britain and France, bourgeois readers devoured police “memoirs” that peddled lurid glimpses into high-profile murders and tawdry street crimes alike. In the United States, readers thrilled to dime-novel sheriffs lassoing rustlers on the range and broadside exploits of Allan Pinkerton and his agents, women included, smashing conspiracies of anarchists, communists, and “Molly Maguires.” In the twentieth century, memoirs bylined by everyone from the FBI’s J. Edgar Hoover to the LAPD’s Daryl F. Gates sold widely and netted their authors serious money in the process. (Hoover laundered his royalties through a nonprofit and became rich.)

The reading public looked to these stories for an understanding of their changing world. From the saloons of the lawless frontier, to the warrens of industrializing cities, to the vacant lots and housing projects of contemporary urban ghettos, cop memoirs have promised insight into their eras’ spaces of disorder, as well as vignettes—titillating, tragic, and comic—of the unruly persons who populate them. Cop memoirs also promise character studies of the people who patrol such dangerous zones, learn their ways, and presumably gain some portable wisdom about society and human nature in the process. The question “Who Watches the Watchers?” has an obvious answer insofar as everyone, it seems, wants to know what makes cops tick, and to see the world that they see.

Of course, whether in the first person or otherwise, not all or even most of these police narratives were actually written by police themselves. Many were ghostwritten by journalists, whose symbiotic relationship with the police has always been something of an open secret. Journalists can become “so coppish themselves,” H.L. Mencken remarked in 1931, that they function as “police buffs,” “police enthusiasts,” and “police fans,” largely dependent on information from the authorities for their stories. Today, as in Mencken’s time, a great deal of crime “reporting” merely reproduces police press releases—and many long-form cop memoirs reproduce not only the stories about cops that audiences want to read, but the stories cops want to tell about themselves.

Read the rest of this article at: The New Republic