What Mongolian Nomads Teach Us About the Digital Future

People who pack up and transport their house twice a year become choosy about their possessions. I recently traveled among the nomads of Mongolia for two weeks and had a chance to inspect their belongings. I was there to photograph their traditional practices, which were more intact than I expected. Along the way I discovered the Mongolians may have a few lessons for the future of digital culture.

The population of Mongolia is 3 million. Half of them live in the capital city of Ulaanbaatar, which may be the least green city in the world. Drab Soviet apartment blocks cram a town without parks, lawns, or trees. The other half of Mongolians live in deeply rural areas. An abrupt boundary at the edge of the city marks the end of the concrete and the beginning of the infinite grasslands that stretch to the horizon.

For the next 600 miles in any direction there is not a single fence on this treeless lawn. The cropped grass wraps the contours like a green rug. This uninterrupted carpet is marred by very few paved roads, and fewer electrical lines. It is perhaps the most primeval landscape on the planet: wide open plains of nothing but grass, rock, and sky.

Read the rest of this article at: Wired

Thinking Like a Mountain

Fantasy answers a lack, however imperfectly. And so much is lacking. Every inhabited continent has been denuded of ecosystems and species. Most North American places have shed wolves, elk, moose, brown bears, panthers, bison, and a variety of fish and wild plants, which were all abundant four hundred years ago. Before those species were driven out, there was the slaughter of the mammoth, the ground sloth, the wild horse. The squirrels, rabbits, and sparrows that surround my North Carolina porch are less signs of burgeoning life than survivors of an apocalypse; so are the revenant coyotes that poach chickens and puppies from the neo-hippie farmsteads outside town. Yet in the restored Arts and Crafts cottages that fill my neighborhood, the children’s bedrooms are as totemic as the Chauvet Cave: covered in animal iconography from the farm, the rain forest, the Cretaceous, and the deep sea. Planet Earth, the BBC series narrated by David Attenborough, makes us invisible participants in lives otherwise as remote as those in the Ramayana. We witness migrations, hunts, nestings, and hatchings. Forty years ago, John Berger called the zoo “an epitaph to a relationship” between people and animals. Today those words could be applied to much of middle-class mass culture: it has become a kind of memorial to the nonhuman world, revived in a thousand representations even as it disappears all at once.

Read the rest of this article at: n+1 Magazine

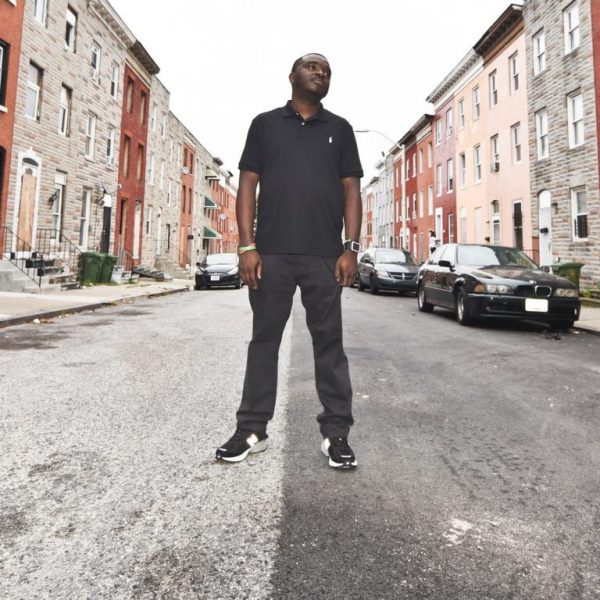

One Drug Dealer, Two Corrupt Cops and a Risky FBI Sting

On a humid summer day in 2004, Davon Mayer stepped out of his house on Bennett Place in the heart of Baltimore. Sixteen years old, Davon was short, plump and baby-faced, still more of a kid than an adolescent. Like many other boys in his neighbourhood, he had long since stopped going to school and was dealing drugs full-time.

On any other day, Davon would have been busy by this hour, trading vials of crack for cash on the pavement, keeping an eye out for the police. But this morning, he was on his way to meet with a narcotics detective named William King. Weeks earlier, the detective had arrested Davon after catching him selling drugs. He had taken Davon to the police station and then let him go, asking that Davon call him. When Davon failed to call, King had paid him a visit to let him know he wasn’t playing around.

As Davon walked to a nearby strip mall where King had arranged to meet, his mind was weighed down by anxiety. What could a city detective possibly want from a small-time drug dealer such as himself? The only answer Davon could think of was that King wanted him to become an informant. The more Davon dwelled on that possibility, the more panicked he got. Where he came from, there was nothing worse than helping the police. To snitch on fellow drug dealers was to invite death.

He got to the mall’s parking lot and saw King’s pickup truck. King was sitting behind the wheel, dressed in sweatpants and a T-shirt. He asked Davon to get in the back seat and turned on the engine. “I have been watching you,” King said, as they drove around. “I like the way you do business.”

Read the rest of this article at: The Guardian

Why Race Is Not a Thing, According to Genetics

Today, scientists routinely map the genomes of the long dead, from Neanderthals to medieval kings. What they’re finding out, says British geneticist Adam Rutherford in A Brief History of Everyone Who Ever Lived, rewrites the story of human life on Earth—with some unexpected twists.

Speaking from the BBC studio in London where he hosts the weekly radio program Inside Science, Rutherford explains how the development of farming changed human biology; why the most important story our genes tell is that we are all family, despite race or tribe; and why it’s not genes that turn people into mass shooters.

If you think of DNA simply as a data storage device, the data it stores is biological information. In us, it’s three billion letters of individual code, or 20,000 genes. Paleogenetics is the study of our DNA from things that have been dead for a long time—paleo simply means old. It’s new because we’ve only invented the technology to do it in the last 10 years and, in a serious way, in the last five years.

What’s interesting is that DNA is far more stable than a digital disk or tape. Under the right conditions, DNA will last for thousands or even hundreds of thousands of years trapped inside the bones of a person or organism. With the advent of our ability to get it out, we can do genome studies on creatures that have been dead for thousands of centuries.

Read the rest of this article at: National Geographic

Walter Isaacson Goes Inside the Most Creative

Mind in History: Leonardo da Vinci

Midway through Walter Isaacson’s luminous new biography, Leonardo Da Vinci, the artist of rising reputation moves from Milan to Florence, and in 1502 agrees to meet the warlord Cesare Borgia. Leonardo at this point is fifty-three, handsome, a success, with a keen eye for elegant form, and happily coupled with a younger man.

Milan had given Leonardo his launch, stability and continuing work. He went back to Florence, where he was from, for new opportunities and commissions. Meanwhile, leaders of Florence, an artistic and commercial power, paid Borgia 36,000 florins in protection money, bribing him not to attack the city.

“Name any odious activity and Borgia was the master of it: murder, treachery, incest, debauchery, wanton cruelty, and corruption. He had a brutal tyrant’s hunger for power combined with a sociopath’s thirst for blood,” writes Isaacson. After some seasoning of gory proof, the author adds: “His only sliver of historical redemption, which is undeserved, came when Machiavelli used him as a model of cunning in The Prince and taught that his ruthlessness was a tool for power.”

Machiavelli has a brief role in the build-up to Leonardo’s encounter with Borgia. The Florentine diplomat-writer, “well-educated but poor,” goes with an influential priest to see Borgia, who had been made a cardinal at eighteen but stepped down after showing “less than zero predilection for piety.”

Simon and Schuster in the book’s press release has disclosed that Leonardo DiCaprio optioned the film rights. Picture Leo as Leonardo, nervous over Machiavelli’s negotiations. Cut to Andy Garcia as Machiavelli, fearful in his approach with the priest inside the ducal palace at Urbino, east of Florence, where the evil Borgia (Al Pacino? Robert De Niro?) sits wizened and coiled. The book continues:

“Borgia knew how to put on a power show. He was seated in a dark room, his bearded and pockmarked face lit by a single candle. He insisted that Florence show him respect and support. Once again a vague accommodation seems to have been reached, and Borgia did not attack. A few days later, probably as part of his arrangement with Florence that Machiavelli had helped to negotiate, Borgia secured the services of the city’s most famous artist and engineer, Leonardo da Vinci.”

Read the rest of this article at: Daily Beast