Every coherent society has a social ideal—an image of what the superior person looks like. In America, from the late 19th century until sometime in the 1950s, the superior person was the Well-Bred Man. Such a man was born into one of the old WASP families that dominated the elite social circles on Fifth Avenue, in New York City; the Main Line, outside Philadelphia; Beacon Hill, in Boston. He was molded at a prep school like Groton or Choate, and came of age at Harvard, Yale, or Princeton. In those days, you didn’t have to be brilliant or hardworking to get into Harvard, but it really helped if you were “clubbable”—good-looking, athletic, graceful, casually elegant, Episcopalian, and white. It really helped, too, if your dad had gone there.

Once on campus, studying was frowned upon. Those who cared about academics—the “grinds”—were social outcasts. But students competed ferociously to get into the elite social clubs: Ivy at Princeton, Skull and Bones at Yale, the Porcellian at Harvard. These clubs provided the well-placed few with the connections that would help them ascend to white-shoe law firms, to prestigious banks, to the State Department, perhaps even to the White House. (From 1901 to 1921, every American president went to Harvard, Yale, or Princeton.) People living according to this social ideal valued not academic accomplishment but refined manners, prudent judgment, and the habit of command. This was the age of social privilege.

Read the rest of this article at: The Atlantic

Why do rocks fall? Before Isaac Newton introduced his revolutionary law of gravity in 1687, many natural scientists and philosophers thought that rocks fell because falling was an essential part of their nature. For Aristotle, seeking the ground was an intrinsic property of rocks. The same principle, he argued, also explained why things like acorns grew into oak trees. According to this explanation, every physical object in the Universe, from rocks to people, moved and changed because it had an internal purpose or goal.

Modern science has rejected this ‘teleological’ way of thinking. In the 17th and 18th centuries, scientists and philosophers began to chip away at Aristotle’s seemingly ‘spooky’ notion of intrinsic causes – spooky because they suggested that rocks and creatures were guided by something not entirely material. For those who rejected these Aristotelean explanations, such as Thomas Hobbes and René Descartes, organisms were simply complex machines animated by mechanisms. ‘Life is but a motion of limbs,’ wrote Hobbes in his Leviathan (1651). ‘For what is the heart, but a spring; and the nerves, but so many strings; and the joints, but so many wheels, giving motion to the whole body.’ The heart does not have the goal of circulating blood. It’s just a spring like any other. For many thinkers at the time, this view had real explanatory benefits because they knew something about how machines worked, including how to fix them. It was in this intellectual environment that Newton developed a powerful mechanical worldview, based on his discovery of gravitational fields. In a Newtonian universe, internal purpose doesn’t cause rocks to fall. They just fall, following a law of nature.

Mechanistic explanations, however, struggled to explain how life develops. How does a grass seed become a blade of grass, in the face of endless disturbances from its environment? Long after the mechanistic revolution, the philosopher Immanuel Kant confronted the stubborn problem of teleology and despaired. In 1790, he wrote in the Critique of Judgment that – as commonly paraphrased – ‘there will never be a Newton for a blade of grass.’ Less than a century later, with the publication of On the Origin of Species (1859), Charles Darwin seemed to crack the problem of biological teleology. Darwin’s ideas about natural selection appeared to explain how organisms, from grass seeds to bats, were able to pursue goals. The directing process was blind variation and the selective retention of favourable variants. Bats who sought moths and had an ever-improved capacity to track and catch them were favoured over those who were less goal directed and therefore had lesser capabilities. Though natural selection seemed to illuminate what Descartes, Hobbes and Kant could not, Darwin’s theory answered only half the problem of teleology. Selection explained where teleological systems like moth-seeking bats come from but didn’t answer how they find their goals.

Read the rest of this article at: Aeon

It’s a unicorn of a summer’s day in 2020; the kind that demands factor 50 and flip-flops. I’m being driven around my neighbourhood by my husband, Arlo, my hair pulled up off my neck and a cool can of something fizzy in my hand. My daily medication has kicked in: a serotonin reuptake inhibitor that I’ve taken for 15 years to ease my low-level anxiety. Without it, I’m no longer sure I can stay with this man I have loved for 12 years. I am mute and smiling passively.

“There’s another one!” he points to the right. “At least it’s not disguised as a tree.” He shakes his head. “Do they think we’re idiots?”

Arlo is updating me on the new 5G masts that have been covertly installed through the Trojan horse of the pandemic. It’s not the day out I’d anticipated for our Saturday, but this is our life now. What began as a polite request to turn off the microwave after use and switch off the router before bed is now the dictum that if one of these emitters of radioactive deathrays pops up on our street “we need to move”.

Read the rest of this article at: The Guardian

On the afternoon of Election Day, Elon Musk stopped by his polling place in South Texas, then headed to one of his private planes, bound for what he hoped would be a victory party for Donald Trump at the Mar-a-Lago Club in Palm Beach, Florida. On the way, Musk held an impromptu political rally. He posted the link to a livestream on his social network, X. “There’s only a few hours left,” Musk said, as the engine hummed and 100,000 or so people listened in. “So just make sure everyone is hounding friends and family to vote, vote, vote.”

Prior to this year, Musk ran six companies: Tesla (electric cars), SpaceX (rockets), Neuralink (brain implants), Boring Co. (tunnels), xAI (artificial intelligence chatbots) and X (Twitter). But in May, he added a seventh operation—America PAC, a political action committee that somehow managed to spend more than $170 million between then and the election.

Even more surprising was the way Musk threw himself personally into the effort. He temporarily relocated to Pennsylvania, where he traveled the state, held marathon Q&A sessions in suburban auditoriums and transformed his personal X presence into a right-wing rapid-response operation. Lots of the jokes he circulated were sexist or racist—or sexist and racist. A huge number of his posts in the final days of the campaign expressed outrage over the euthanization of a porn performer’s pet squirrel.

Musk’s signature blend of transgressive humor and brazen behavior paid off, perhaps because, in Trump, he’d found a candidate who matched those traits perfectly. On Election Day the twice-impeached, 34-times-convicted felon ex-president turned out his usual base of older, White voters—and added a new cohort that was younger, more diverse and largely male. The type of guy who likes Elon Musk, in other words. “What he did is lower the barrier to being a Trump supporter,” says Josiah Gaiter, a vice president at political marketing agency Harris Media. Among younger men, “now it’s OK to like Trump.”

Read the rest of this article at: Bloomberg

Twenty-seven degrees in a Port-A-Jon, the seat freezing my ass. I’m in the dark with a little flashlight. Chemically treated feces and urine splash up onto my anus. The wind howls, shaking the plastic structure. My hands go numb.

3:00 a.m., parked in a public lot across the street from the town beach in Westerly, Rhode Island. Just woke up, sleep evasive. It’s my first week out here. I pour an iced coffee from my cooler. I’m walking around the front of the Toyota I’m now living in when a car pulls into the lot, comes toward me. I see only headlights illuminating my fatigue and the red plastic party cup in my hand. Must be a cop. Someone gets out and approaches. It is a cop, young. I’m not afraid, exactly, but I’m also not yet used to being homeless.

“How you doing?” he says.

“Good.”

“Just hanging out?”

“Yes.”

“Are you okay?”

“Yes.”

“Do you need anything?”

“No.”

“Okay. Just checking. Have a good night.”

In the morning, I awake with back pain. Sleeping in the driver’s seat will be an acquired skill.

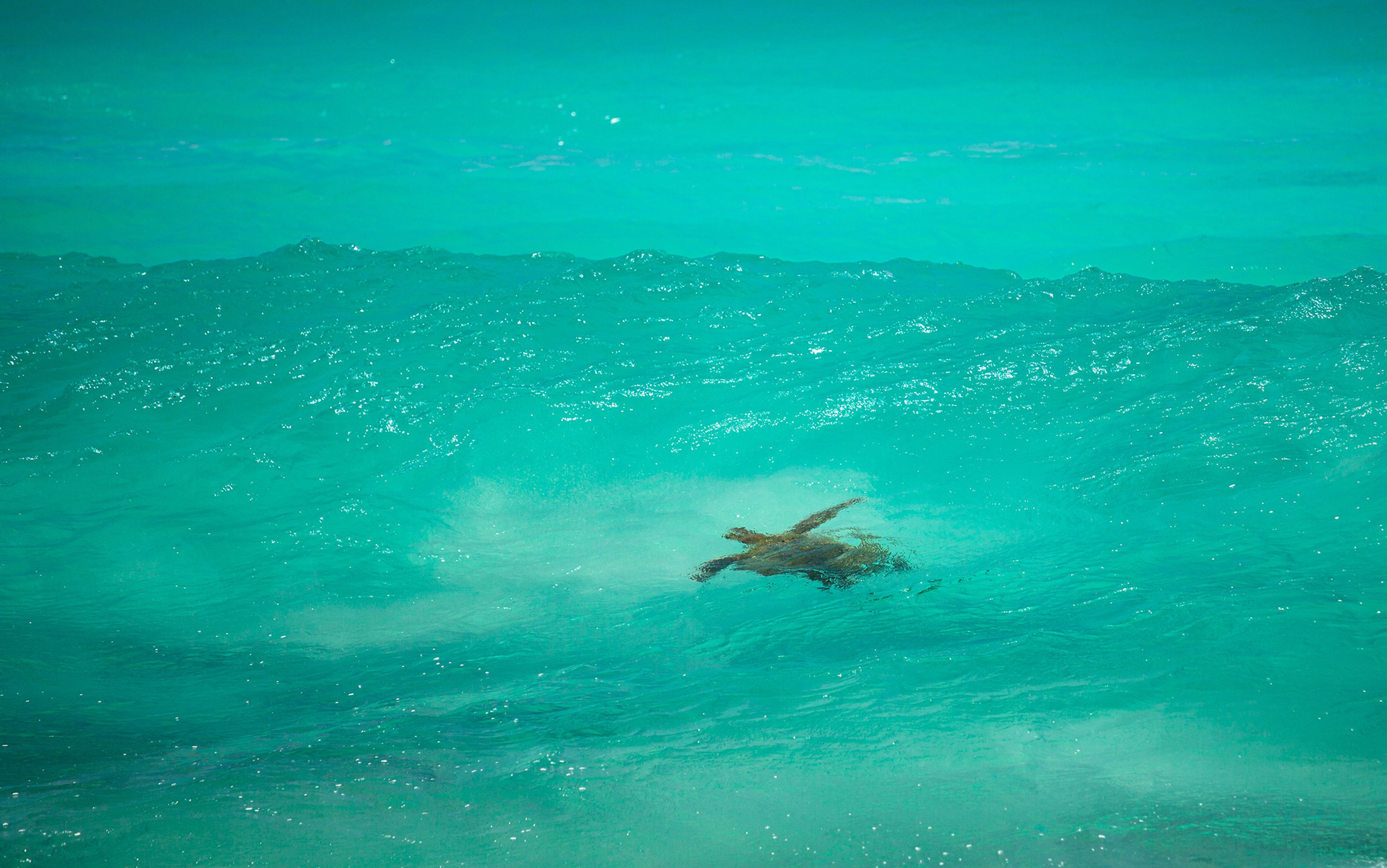

Sun-bleached fences wrap the perimeter of the dunes, blown over by the unrelenting winds off the cold Atlantic. I park at the beach most days and have spent all but one night here. Lovely Lady Lily, the sweet and wild angel with fur, is with me. The entire backseat is hers and she is adjusting to the car well, because I’m here and we are close. Her daily routine has improved in some ways. When we lived in the house, she snoozed on the couch, walked in the yard, and got to the beach, her favorite place, a couple times a week. Now she runs on the beach several times a day, hunting the tide line for shellfish. She crunches down crabs and tears the meat out of quahogs. And if there’s a fish? She found a single minnow on a beach two miles long.

The author was a reporter and arts critic for outlets including The Boston Globe and Reuters. Today he fills notebooks with novels, poetry, and stories. His guitar is sometimes a desk. (He props it upside down on his lap.)

My morning routine is taking gabapentin (an anti-seizure medication that also alleviates psychic and neuropathic pain and brightens my perception), lamotrigine (another anti-seizure medicine, but for me it helps my mental energy and cuts through fog, because gabapentin creates fog), fluoxetine (Prozac, an antidepressant), and Adderall (for focus and energy, because after the manic depression struck in 1997, my brain was a flat tire), walking the beach with Lily, getting coffee at the Mobil station up the road, and writing on an HP laptop I got two months ago that has already had one power-input jack fail. It sits on an upside-down acoustic guitar resting on my lap, a 12V/120V converter plugged into the lighter with the car running. I play the guitar first thing every morning, songs I’ve written. The rest of the day, I flip it over and it’s my desk.

When we’re on the beach early, we usually see John. Lily used to jump on his legs, and he didn’t like it. He’s about seventy and has the bearing and haircut of a military person. He walks the beach looking for sea glass.

Read the rest of this article at: Esquire