A little more than a year ago, Elon Musk began his reign at Twitter with an elaborately staged pun. On Wednesday, October 26, 2022, he posted a tweet with a video that showed him carrying a sink through the lobby of the company’s San Francisco headquarters. “Entering Twitter HQ—let that sink in!” he wrote. At the time, I was a coder for Twitter’s language-infrastructure team. (If you’ve ever used Twitter’s translation feature, or are using Twitter in a language other than English, that was us.) I saw Musk’s tweet when it was shared in a company-wide Slack channel. He looked like a giddy warlord entering an enemy stronghold he’d besieged for months.

There were no more updates until the next day, when a Twitter employee shared a tweet from CNBC: “Elon Musk now in charge of Twitter, CEO and CFO have left, sources say.” The ambiguity of the phrase “have left” was soon clarified by a Times article reporting that Twitter’s C.E.O., C.F.O., and general counsel had been fired, along with its head of legal, policy, and trust. Originally, the acquisition had been slated to close on Friday, but Musk pulled a switcheroo by “fast-closing” the deal on Thursday afternoon. This maneuver allowed him to fire the executives “for cause,” which denied them severance and stock options. The vibe in the office was jokey and un-self-pitying. Everyone seemed in for some grim comedy while it lasted.

Musk filled the vacant leadership suite with his lawyer-fixer Alex Spiro and a few others whom the employees collectively called “the goons.” Some key internal managers kissed the ring and enlisted themselves as Musk’s lieutenants; another reportedly puked into a trash can when asked to fire hundreds of people. Half of the workforce was laid off, but those whose roles turned out to be somewhat critical were then begged to return. Some unlucky engineers were dragooned into launching the new Twitter Blue feature, which would charge users $7.99 per month for a “verified” check mark; the rollout was catastrophic. “We are excited to announce insulin is free now,” a newly verified account impersonating the pharmaceutical giant Eli Lilly tweeted; the pharma’s market valuation went down by billions that day. Twitter Blue was the first in a series of pratfalls that would slash sixty per cent of the company’s advertising revenue and lead to an exodus of users to other platforms.

I wasn’t laid off, but anyone with functioning nerve endings could see that staying would offer no joy. At 12 A.M. on the day before Thanksgiving, Musk sent an e-mail with the subject line “A Fork in the Road.” He wrote, “Going forward, to build a breakthrough Twitter 2.0 and succeed in an increasingly competitive world, we will need to be extremely hardcore.” The e-mail included a link to a Google form that needed to be filled out by 5 P.M., East Coast time, the next day. It had one question—“Would you like to stay at Twitter?”—that had one answer: “Yes.” I am not hard-core. I took the exit.

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

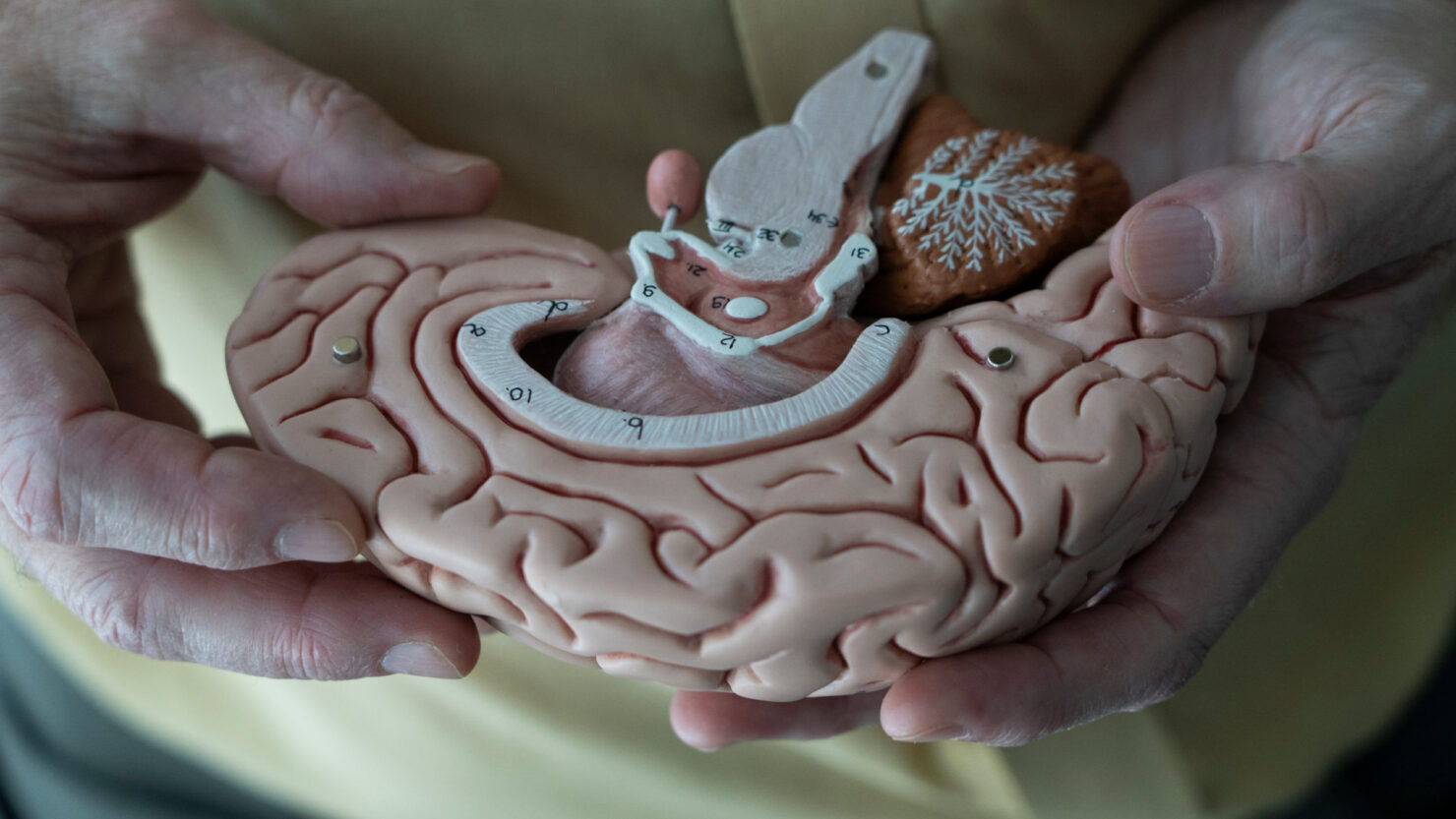

One afternoon in May 2020, Jerry Tang, a Ph.D. student in computer science at the University of Texas at Austin, sat staring at a cryptic string of words scrawled across his computer screen:

“I am not finished yet to start my career at twenty without having gotten my license I never have to pull out and run back to my parents to take me home.”

The sentence was jumbled and agrammatical. But to Tang, it represented a remarkable feat: A computer pulling a thought, however disjointed, from a person’s mind.

For weeks, ever since the pandemic had shuttered his university and forced his lab work online, Tang had been at home tweaking a semantic decoder — a brain-computer interface, or BCI, that generates text from brain scans. Prior to the university’s closure, study participants had been providing data to train the decoder for months, listening to hours of storytelling podcasts while a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) machine logged their brain responses. Then, the participants had listened to a new story — one that had not been used to train the algorithm — and those fMRI scans were fed into the decoder, which used GPT1, a predecessor to the ubiquitous AI chatbot ChatGPT, to spit out a text prediction of what it thought the participant had heard. For this snippet, Tang compared it to the original story:

“Although I’m twenty-three years old I don’t have my driver’s license yet and I just jumped out right when I needed to and she says well why don’t you come back to my house and I’ll give you a ride.”

The decoder was not only capturing the gist of the original, but also producing exact matches of specific words — twenty, license. When Tang shared the results with his adviser, a UT Austin neuroscientist named Alexander Huth who had been working towards building such a decoder for nearly a decade, Huth was floored. “Holy shit,” Huth recalled saying. “This is actually working.” By the fall of 2021, the scientists were testing the device with no external stimuli at all — participants simply imagined a story and the decoder spat out a recognizable, albeit somewhat hazy, description of it. “What both of those experiments kind of point to,” said Huth, “is the fact that what we’re able to read out here was really like the thoughts, like the idea.”

Read the rest of this article at: Undark

On January 1, Future Perfect published its predictions for 2024. The forecasts range from the number of poultry that will be culled because of bird flu this year to which film will win the Oscar for Best Picture. (Oppenheimer — take it to the bank.) But no single subject was covered by more predictions than who will win some of the most important elections around the world this year.

That’s because 2024 will be the biggest election year in history. More than 60 countries representing half the world’s population will go to the polls in 2024, with an estimated 4 billion people voting in presidential, legislative, and local elections. Those elections will range from the massive — India’s multi-day legislative elections (the largest in the world) and Indonesia’s presidential poll, the world’s biggest single-day vote — to tiny North Macedonia’s presidential election.

Read the rest of this article at: Vox

As the 14th season of Bravo’s Real Housewives of New York City came to a close this fall, I found myself on Reddit, reading rumors about the marriage and divorce timeline of one of the show’s stars. Redditors wanted more clues about a fishy relationship history to see if they could uncover a cheating scandal.

Were divorce papers public record in New York? I wondered. I did a quick Google search to find out.

The search results page was filled with my question’s exact words, repeated across site after site — websites for law firms, posts on forums, ads for creepy lookup tools — but the answer to my actual question was harder to find. At the top of the results page on my phone, Google offered two featured snippets of information quoting different websites. The first one: “Divorce records are not public in New York due to the sensitive nature of many divorce proceedings.” The second: “Due to the state’s underlying legislation regarding family law cases, each divorce is a matter of public record.”

Google bolded both snippets, but it wasn’t clear to me how they squared. I clicked on both.

The two law firm websites were part of an ecosystem I didn’t know existed until I accidentally went looking for it. Law firms across different fields — family law, personal injury, employment lawyers — have blogs full of keyword-addled articles being churned out at a surprisingly fast clip. The goal for firms is simple: be the top result to pop up on Google when someone is looking for legal help. The searcher might just end up hiring them.

Many of these blog posts are written by people like E., a self-employed content writer who juggles law firm clients that want Google-friendly content. E. does not have a legal background; they’re just a competent writer who can turn in clean copy. They trawl health department records, looking for nursing homes that get citations for neglect or other infractions. Then E. writes a blog post about it for a firm, making sure to include the name of the offender and the wrongdoing — keywords for which concerned patients or families will likely be searching. (E. requested anonymity so as to not jeopardize their employment.)

“My bosses, they all don’t want anyone else to know that they use me or that we have the specific process that we have,” E. says. Their name is nowhere to be found, but their writing is often the first thing a searcher will see. The pages were made to be found by people like me.

Read the rest of this article at: The Verge

The Cough That Doesn’t End

I was at a long-awaited panel discussion at my friends’ private home, listening to Senator Kristen Gillibrand speak about paid leave and reproductive rights with women’s-health entrepreneurs Priyanka Jain and Alessandra Henderson, when I first heard it: the Cough.

Henderson, the founder of a women’s-health company called Elektra Health, coughed discreetly from the makeshift stage. Then she coughed again. It was dry and quick and frequent. Every so often, she would turn her head, raise her hands, and, behind the swishy curtain of her chic blonde bob, cough. A woman stole over and slipped her a cough drop. Gillibrand had warmed up and was on a tear about TikTok. (Not a fan, by the way.) And still, discreetly but certainly not imperceptibly, coughing. Henderson did not otherwise seem sick. She was a power woman on a panel with a senator, in peak form, but what can I say? These days, you notice the cough.

Who among us has not walked the streets of New York beset by the scourge of the season, the persistent hacking cough? Maybe you currently have one yourself, or the person in the subway seat next to you is coughing, or you’ve narrowly escaped catching a cold from your throat-clearing cubicle neighbor. Even if you’re been personally spared, you’ve likely noticed that the entire city is hacking away right now, or maybe in this endless COVID era, it’s all just harder to ignore. Respiratory-virus season is in full swing, COVID is still here, and the CDC sent an alert out last week that vaccinations are low. The cough-industrial complex is booming, but despite the fact that we now have CRISPR gene editing and a postpartum-depression pill, it’s a crapshoot as to what cough medicine actually works. In September, an FDA advisory panel ruled that phenylephrine, the main ingredient in many decongestants, doesn’t actually do anything. Phenylephrine is for stuffy noses, but it’s bundled in a bunch of the top cough medicines to treat a cross-section of cold symptoms.

After the talk, I asked Henderson about her cough. “I’m not contagious. I would never be here. I tested myself again this morning,” she said immediately. “I get this many times a year, and so no matter how I’m sick, or what I’m sick with, it always manifests in my chest. I just have very weak lungs.” It turned out that Henderson had fluid in her lungs as a newborn. I also have very weak lungs, so I get it. Mine trace back to a bout of asthmatic bronchitis that sent me to the hospital for a week in third grade and again in my teens after finding out the hard way that I had a cat allergy. I have an inhaler, but when I get sick, I, too, feel it in my chest. And when it gets bad, there is the cough.

Read the rest of this article at: The Cut

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/73018893/1871751876.0.jpg)