This wasn’t Supposed to happen. In 2020, in a house surrounded by fields in the Irish countryside, Liam, 19, sat at his laptop, an energy drink fizzing at his elbow. He leaned in for a better look at the profile photo and, sure enough, saw the face of an old rugby friend looking back at him.

Just weeks earlier, Liam, whose name has been changed to protect his privacy, had been living in Waterford, in Southeast Ireland, about to start his second year at university. Then Covid-19 shut down the city and his university’s campus. On any Saturday on the main street, there were now more pigeons than people. Pubs and cafés shut their doors, and job opportunities dried up. “Money-wise it was worrying,” he says.

Increasingly concerned, Liam responded to a Facebook ad for a “freelance customer support representative,” working remotely for vDesk, a company based in Cyprus. He was invited to an online interview. At the end of the call, the interviewer asked how he would feel about moderating dating websites.

“I thought I might be moderating hateful content on Tinder, something like that,” he says, “they weren’t clear about the kind of work it would really be.”

Read the rest of this article at: Wired

AT FIRST, the only indication that there was anything out of the ordinary was a large piece of cardboard that read RIP JORDAN NEELY. A BLACK MAN WAS KILLED BY A WHITE MAN HERE. NYPD HAS NOT ARRESTED THE MURDERER. WE WANT JUSTICE. NYC, LOVE AND PROTECT YOUR FELLOW MAN. DON’T MOVE HERE IF YOU’RE SCARED OF YOUR NEIGHBORS. The block letters bobbed over the heads of two dozen people gathered on the uptown Broadway-Lafayette platform to mourn Neely, a homeless man who had been murdered on the F train by a white civilian, at that point still unnamed, two days earlier. More details as I approached: WHO KILLED JORDAN NEELY? scrawled in sharpie against the dirty white tile of a support beam, a group of reporters, slightly more cops than usual, and, on the ground, a bouquet of purple flowers and a few of those tall white candles encased in glass cylinders, unlit. People and cameras gathered around the person holding the sign, who took advantage of lulls in the ambient MTA din to address the crowd: They want to clear this city of people who actually live here and are from here for rich gentrifiers who call the fucking cops on their neighbors for playing music too loud. Don’t call the fucking cops on your neighbors, she pleaded. If you see someone who needs help on the subway, fucking help them. Help them. Shouts and nods and hums of support.

It was Wednesday afternoon. Jordan Neely was murdered around 2:30 PM on Monday. Like everyone else, I had found out about the murder through a forty-one-second-long video of Neely being choked and restrained by three men that was circulating on Twitter. I saw the thumbnail, but didn’t watch it, didn’t need to—I knew the video would only show me that same static scene stretched out obscenely over time; I knew that the ex-Marine’s arm would not move from Neely’s neck, that the two other men would not let Neely move, and that nobody was going to interrupt the lynching that was occurring in front of them, in the middle of their commute. On Friday we would learn the name of the murderer—Daniel Penny—but on Wednesday there was still no name, just a killer, two accomplices, a carful of witnesses, and a man who was killed for being homeless.

Read the rest of this article at: n+1

Nearly 200 years ago, the slave ship Guerrero sunk, killing forty-one Africans. The wreck vanished. Until now. A group of divers led by Ken Stewart, a Black man in his seventies, believe they found it in the Florida Keys. But in a state that banned critical race theory, telling this story is suddenly complicated.

Thirty feet under the choppy blue waves of the Florida Keys, Kramer Wimberley points to the broken, bleached white coral scattered beneath us like bones. Then he slices his hand across his throat, dead. Marine life here at Molasses Reef, located five miles southeast of Key Largo, is dying from rising temperatures, pollution, and disease. Without action, the once pristine reef, like the others along the Keys, is in danger of being lost and forgotten.

Read the rest of this article at: Esquire

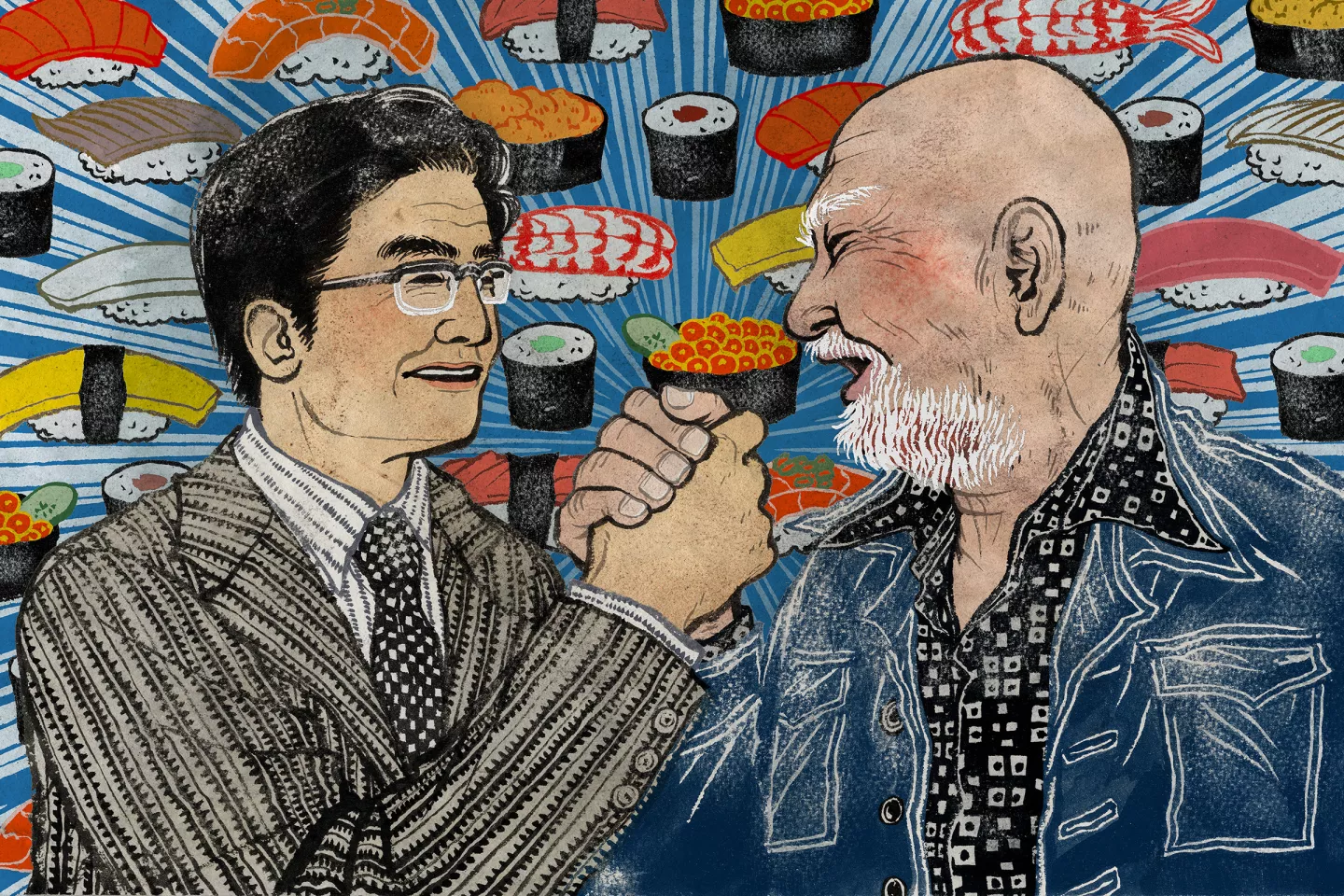

It was the meal that changed how Angelenos eat.

And it happened more than 5,000 miles from Los Angeles.

When Noritoshi Kanai and Harry Wolff Jr. sat down for dinner in Tokyo one night in 1965, they had no way of knowing they were about to stumble onto an idea that would upend American dining — and their own lives.

On this evening, the colleagues had more urgent concerns on their minds: how to salvage a foundering trip in Asia that was launched to find a novel food product to import to the U.S.

That item, it turns out, was actually on the menu.

Sushi.

Kanai, who managed Mutual Trading Co., an L.A. wholesaler of Japanese food products, had suggested the restaurant, a family-run spot in the Ginza district called Shinnosuke. Wolff had never eaten sushi, but Kanai figured he’d be game.

“He’d try anything,” Kanai recalled, laughing.

Before long, Shinnosuke’s sushi chef was turning out a cascade of nigiri.

Tuna. Octopus. Cuttlefish. Scallop. Sea bream.

Wolff ate with enthusiasm. But the significance of the meal wouldn’t become apparent until five days later.

Read the rest of this article at: Los Angeles Times

The street I grew up on in Moore County, North Carolina, is unrecognizable now. What was once a mix of modest, low-slung ranch-style houses interspersed with pockets of turkey oak scrub has been invaded by gargantuan homes with equally oversized trucks parked in the driveway. They tower over their older neighbors at a tragicomical scale difficult to convey, each identically crafted for maximum cheapness and interchangeability. Behold the McMansion in all its readymade, disposable grandeur.

Unlike the McMansions that predominated prior to the financial crisis—over-inflated, fake-stuccoed colonials festooned with some tacky approximation of European finery—the new iterations are whitewashed and modern, their windows undifferentiated voids. The compound hip roofs of the aughts have been replaced with peaky clusters of clumsy gables, a nod to the faux-folksy “modern farmhouse” trend ushered in ten years ago by HGTV. Moore County, meanwhile, is a prototypical American sprawl scenario: boundless, monotonous growth laying waste to what was once a network of stolid retirement communities orbiting the quiet resort town of Pinehurst. Who the hell are all these new interlopers? When I ask, my mother simply says, “They’re military.” Indeed, Moore County has become a de facto upscale exurb for high-level military personnel and civil servants working in nearby Fort Bragg. But it isn’t only happening in North Carolina: like something out of Invasion of the Body Snatchers, the McMansion has replicated, reduplicated, and overtaken the country overnight.

Read the rest of this article at: The Baffler