“Do you remember what kind of beer it was?”

Andy Hunter pauses for so long before answering my question, it’s awkward. He’s racking his brain. I’ve asked him to tell me about the night he came up with the idea that led to his improbably successful bookselling startup, Bookshop.org. As a former magazine editor, he wants to get the details right.

He remembers the easy stuff: It was 2018. He was on the road for work. At the time, Hunter ran the midsize literary publishing house Catapult, a job that required schmoozing at industry events. The night of his big brainstorm, he was away from his two young daughters and his usual evening obligations—dishes, bedtime rituals—and had a rare moment to think, and drink a beer.

But what kind of beer? “It was, uh, a Dogfish Head IPA,” Hunter finally answers. OK, so, picture this: There he is, alone in a tidy Airbnb, a light-blue bungalow on a quiet road in Berkeley, California. His brown hair is a little mussed, and he’s nursing a pale ale. He’s grooving to music. (“You can say I was listening to Silver Jews,” Hunter says.)

He couldn’t stop thinking about something a board member of the American Booksellers Association, the industry’s largest trade group, had said to him during a recent work dinner. What if ecommerce was a boon for independent bookstores, instead of being their existential threat? The Booksellers Association ran IndieBound, a program that gives bloggers and journalists a way to link to indies instead of Amazon when they cite or review a book. But it hadn’t gained much traction.

Read the rest of this article at: Wired

Lou Lou Ann Dagen died in April 2020 in a Grand Rapids, Michigan, hospital, without her family. She had lived in a nursing home for 10 years, and communicated with her sister, and the world, through Alexa. Two days after Lou Ann died of complications from coronavirus, her sister found recordings of Lou Ann’s voice asking Alexa, “How do I get help?”

One day last summer, I woke up and reached for my phone, as I do every morning, as you do every morning. Maybe you are reading this in your bed on your phone wherever you are this morning. I was having what I thought of as a weak stretch in my life, when I didn’t have a regular job, and when just deciding what I would do to avoid writing, or having a single thought about my email, was enough to short-circuit me and I would find myself still in pajamas at 5 p.m., pacing and crying, Googling What’s wrong with me and waiting until it was OK to go to bed again.

In such weak stretches, among the many indulgences I permit myself is the minor suboptimal habit of actually sleeping with my phone. Under the other pillow next to me, where no one sleeps. In other, more robust stretches, my phone spends the night plugged in about a foot away on the nightstand, and I can still reach it if I wake up and want to look at it, but it’s tethered. When I let it sleep freely with me, I can turn over while I look at it. I can look at it while I’m lying on my left side, and then I can turn over and look at it while I’m lying on my right side. I just charge it the next day, because it doesn’t matter if either of us is ready to go in the morning.

Read the rest of this article at: Slate

If you’re curious to know what it was like to work at BuzzFeed News in the salad days of the mid-2010s, here is a representative anecdote: I was sitting at my desk one morning, dreadfully hungover and editing a story titled “The Definitive Oral History of the Wikipedia Photo for ‘Grinding,’” when the sounds of a screaming man broke my trance. I looked up to see Tracy Morgan three feet away, surrounded by a small entourage of handlers.

Morgan was barreling through the office, lifting his shirt up, smacking his belly, and cracking jokes about how pale all of us internet writers looked. I remember our lone investigative reporter, Alex Campbell, scurrying away from his desk, a row away from mine, to continue his reporting call in silence. A few months later, the story he’d been working on would help free an innocent woman from prison. Morgan’s chattering faded, and the newsroom returned to its ambient humming of frenetic keyboard clacking—the sound of the internet being made. Hardly anyone had batted an eye.

Read the rest of this article at: The Atlantic

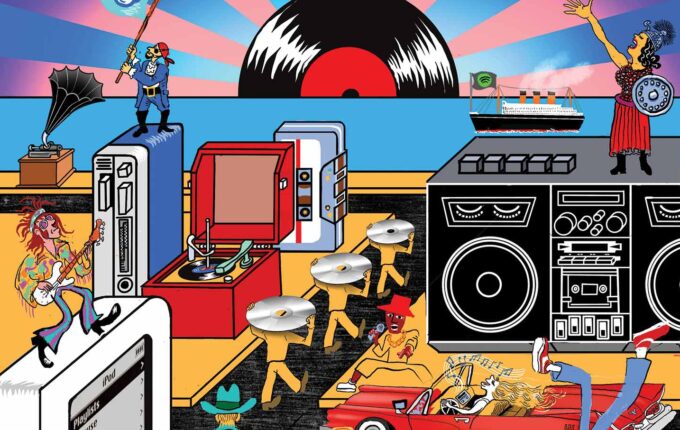

In 1902, Thomas Edison’s wax cylinder was finally sturdy enough to be sold in bulk, and Americans started buying recordings of music for the home phonograph. There was money to be made from this novel idea: Enrico Caruso’s rendition of “Vesti la giubba” from Pagliacci would sell a million copies by the end of 1903. Soon enough, the 78-rpm record, a brittle disc of lacquer with grooves on each side, became the standard. The technology seems primitive—a needle riding a groove without even a basic electric current—but it could be very loud. Ma Rainey recorded a string of important hits in the 1920s, and the Mother of the Blues still has the power to make a weak man change his cheating ways—especially if you hear her sermon blaring out of the old Victrola, its bent bell horn projecting ominously into the room.

Those early 78s are short (just three minutes a side), compressed in sonic range (the bass register is notably weak), and garnished by a constant low sizzle like that of a frying steak. The race for improved technology was on. Engineers started using electricity in the late ’20s and magnetic tape in the ’30s, but one postwar development proved to be definitive: the long-playing microgroove vinyl disc, 10 inches in diameter, later expanded to 12 inches, rotating smoothly at 33⅓ revolutions per minute. The key was duration: Up to 45 minutes of music could now stand as a unified statement.

“It’s really from the international level all the way down that we have this problem of ‘cybercrime’ as an overbroad or even meaningless concept,” says Andrew Crocker, a senior staff attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a nonprofit that focuses on civil liberties in the digital era.

Read the rest of this article at: The Nation

A T THE EDGE of the Okavango Delta in northern Namibia, the land is so flat that I could see the top of ReconAfrica’s drill rig when we were about a mile away. ReconAfrica is a small Canadian oil-and-gas-exploration company that claimed to have discovered an oil-and-gas basin rivaling anything in Texas near one of the most pristine ecosystems in Africa, a remote, wide-open landscape where herds of wild elephants roam and endangered wild dogs hunt in packs. News of ReconAfrica’s alleged discovery had caused its stock price to shoot up, giving the company a value of nearly $2 billion before it ever pumped a drop of oil out of the ground. The discovery is also poised to kick off an oil-and-gas boom in Africa just when it has become clear to most scientists and political leaders that, to maintain a hospitable climate, fossil fuels need to stay in the ground. As we drove closer to the rig, I noticed a Namibian flag and a Canadian flag flying side by side on top, as if to suggest this rig were a symbol of international cooperation rather than one of planetary destruction.

I had driven up to the drill site from Rundu, a Namibian town about two hours away, in a beat-to-shit Land Cruiser with Steve Stockhall, a Botswana-based wildlife guide and photographer, and Stefan Kudumo, a Namibian activist and translator. We were all a little nervous as we approached the site — oil companies in Africa don’t have a reputation for playing nice with inquisitive journalists.

At the turnoff to the dirt road that leads to the rig, a pickup truck was parked, with three guys in sunglasses leaning against it. They wore black boots with khaki pants and military-style shirts. They eyed us as we drove by. We pulled ahead a few hundred feet, then parked and stepped out. The rig was about 200 feet away, surrounded by a chain-link fence. In the distance, I could hear the grinding and pounding of the drill bit as it pushed through 3,000 feet of rock.

Read the rest of this article at: Rollingstone