Product placement is over. It’s so lame. Why smuggle an item of merchandise into a movie, like contraband, and have people snicker at the subterfuge, when you can declare your product openly and lay it on the table? Why not make a film about the merch? That was the case with “Steve Jobs” (2015), which unfolded the creation myth of Apple; with “The Founder” (2016), which did the same for McDonald’s; with “Tetris,” now on Apple TV+; with the upcoming “BlackBerry,” which is not, alas, about the harvesting of soft fruits; and with “Joy” (2015), which gave us our first chance—pray God it not be our last—to watch Jennifer Lawrence trying her hardest to sell mops.

The latest example of a ready-branded film is “Air,” the product on this occasion being the Air Jordan. The movie is written by Alex Convery and directed by Ben Affleck, who also appears onscreen as Phil Knight, the co-founder and C.E.O. of Nike. The company, of course, was named for a Greek goddess, which may explain why Affleck is decked out with a beard and a hair style that fell out of fashion in 438 B.C. He also gets to drive a purple Porsche and to wear pink running pants, perilously loose around the crotch. Any looser and he’d risk an NC-17 rating. Whether or not Affleck is atoning for the shame of playing Batman, in the DC franchise, it’s pretty sporting of him, in his own film, to set himself up as a comprehensive jerk.

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

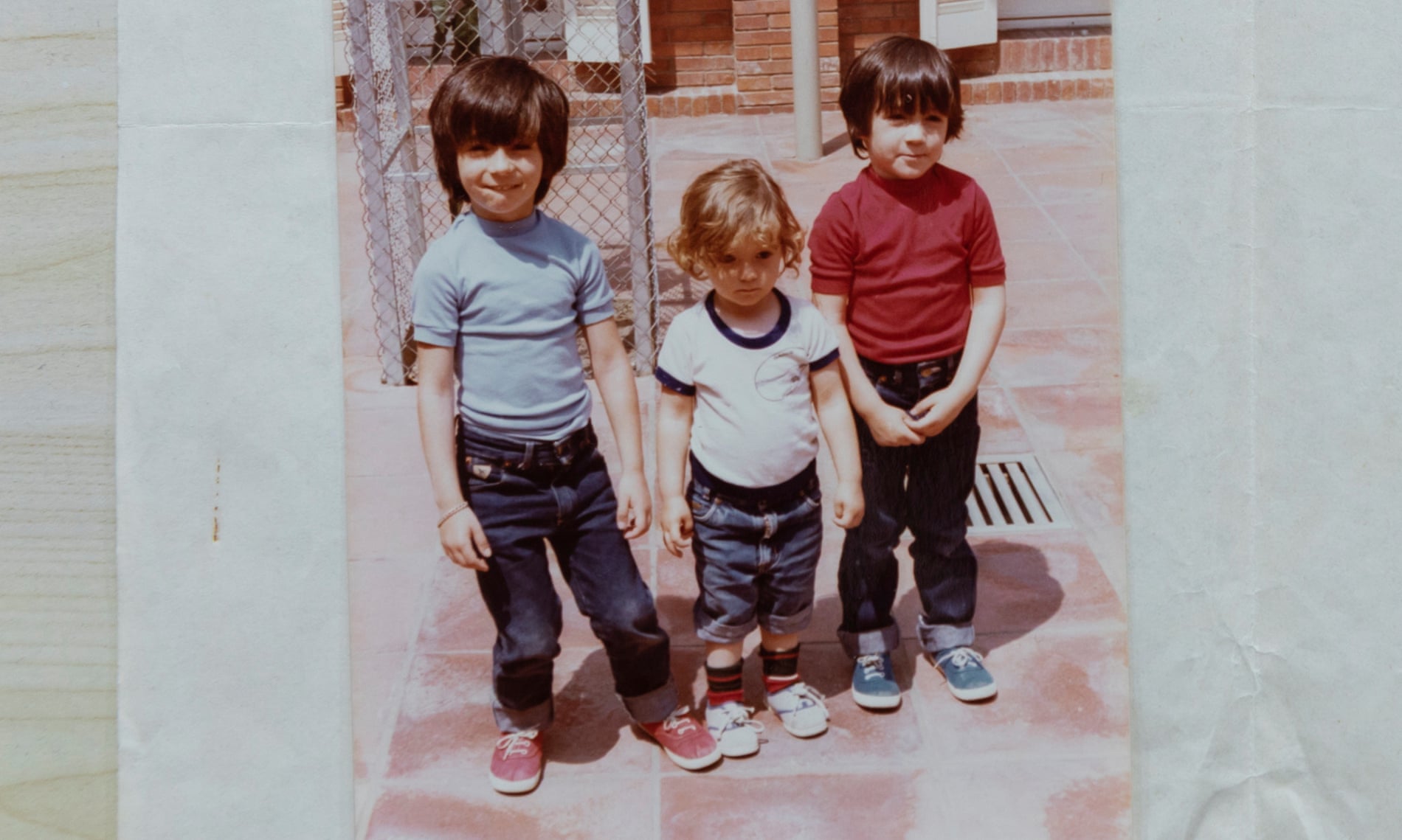

Three Abandoned Children, Two Missing Parents and A 40-year Mystery

On 22 April 1984, a sandy-haired, ringleted two-year-old girl named Elvira was driven with her brothers, Ricard and Ramón, aged four and five, to a grand railway terminus in Barcelona. The children, dressed in designer clothes, rode in a white Mercedes-Benz driven by their father’s French friend Denis. He parked near the modernist Estación de Francia and walked them into the hangar-like hall, which had shiny, patterned marble floors and was topped by two glass domes. Once there, he told the children to wait while he bought sweets.

The three siblings waited, but Denis did not return. Eventually, Elvira started crying. A railway worker asked what was wrong and Ramón, who spoke French and Spanish, explained. The police were called, but when they asked the children their parents’ names, they did not know. Nor could the children give their own surnames, or say where they lived – except that, until recently, it had been Paris.

Five-year-olds usually know such basic things, but the police were not overly concerned. Children are not generally abandoned without explanation, especially in groups of three. Authorities expected that very soon, someone – a relative, friend or schoolteacher – would report them missing and the mystery would be solved. They made no attempt to alert the press or appeal to the public for help.

Read the rest of this article at: The Guardian

On April 20, 1848, Alfred Russel Wallace and Henry Walter Bates set off for the Amazon on a boat named Mischief. The two young men—Bates was twenty-three, Wallace twenty-five—had met a few years earlier, probably at a library in Leicester, in England’s East Midlands. Both were passionate naturalists, and both were strapped for cash. (Neither had been able to afford university.) To finance their adventures, they planned to ship specimens back to London, where they could be sold to wealthy collectors.

For reasons that no one has ever been able to explain—but that many have speculated about—Wallace and Bates separated soon after they reached Brazil. In the decade that followed, Wallace amassed an immense trove of new species; lost most of them in a ship fire; set off again, for Southeast Asia; and, with Charles Darwin, discovered natural selection.

Bates, meanwhile, remained in Brazil. He sailed up the Tapajós, an Amazon tributary, and then up the Cupari, a tributary of the Tapajós. Travel in the region was often agonizingly slow; to get from the town of Óbidos to Manaus, a journey of less than four hundred miles, took him nine weeks. (At some point during the trip, he was robbed of most of the money he was carrying.) Bates would find a congenial town and spend months, even years, there, making daily forays into the surrounding rain forest. He tromped around in a checked shirt and denim pants, an outfit considered outré by the British merchants he encountered in Brazil, who wore their top hats rain or shine.

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

It’s all wrong. The wrongness is pervasive; you could not, if asked, identify the it or the its that went wrong. Wrongness leaches into everything, like the microplastics you read about, which may or may not be reducing sperm count in men, which may or may not be good, in the long run—it’s something to do with the environment. Someone wanted you to feel one way or the other about it, but you can’t remember who or why or whether you agreed with him. Everyone speaks so authoritatively, whether it’s on the evening news or a podcast, in an Internet video or a book, or even in one of those Twitter threads that begins (irksomely, you once felt, but now you don’t notice) with the little picture of a spool. Authority makes them all sound the same; it crosses all their faces and leaves many of the same furrows. Only afterward, trying to add it all up, do you half-remember that none of them agreed with each other. But the wrongness you can be sure of. It is like God, undergirding all things.

One day, you stumble across something—a long video, an article, a conversation (How rare those are! You must make more time for them…) with a learned friend. The same self-righteousness of authority crosses his face, the tinniness of certainty issued from his mouth too, but this time what he says sticks. It seems to explain the wrongness. Or not even explain it, really—just make it stand still. It was this thing that was wrong. The monster disclosed himself. He was something small and definable—a vaccine, a chemical—that spreads until it can’t be isolated, or he was something large and indefinable—“wokeness,” “CRT”—that terminates in many small, sharp wrongnesses. Or maybe it was the second sort of thing, but epitomized in a single image, so that it sounds like the first: The Cathedral. The cabal. But for a second, you could see the wrongness. How clarifying, simply to see it. You felt something like desire.

Read the rest of this article at: The Hedgehog Review

When we lived in England my days had a familiar rhythm. Each morning, my mother flung open the curtains in my room, and I tugged my school jumper over my head and pulled on my skirt before tumbling downstairs to eat cereal with my younger brother Jon. After school, we’d play on the swing in our garden, or crouch at the far end of the stream to watch dragonflies hovering above the gold-green surface.

I was used to this rhythm; I liked it and thought it would never change. Until one morning over breakfast, my father announced that we were going to sail around the world.

I paused, a spoonful of cornflakes halfway to my mouth.

“We’re going to follow Captain Cook,” Dad said. “After all, we share the captain’s surname, so who better to do it?” He picked up his cigarette and leaned back in his seat.

“Are you joking?” I asked.

Next to me, Jon watched Dad, his lips parted.

“Not at all,” said my father, puffing out a cloud of smoke. “I’m deadly serious.”

“But why?”

“Well, someone needs to mark the 200th anniversary of Cook’s third voyage, don’t they?” he said, raising his eyebrows at my mother.

“Of course they do, Gordon,” said Mum, returning his smile.

“I’ve told you kids about the captain,” said Dad, stubbing out his cigarette in the ashtray. “He was an incredible man. The people who were going to recreate his first and second voyages didn’t get their act together in time, so this is the last opportunity.”

“How long will we be gone?” I asked.

“Three years. By the time we get back, you’ll have seen more places than most people will visit in a lifetime. We’ll sail down to South America, then cross the Atlantic Ocean to South Africa and Australia. From there, it’s on to Hawaii and Russia.”

The clock was ticking on the wall. I looked out of the window at the empty swing. Dad had taken us sailing before, but this was different.

Read the rest of this article at: The Guardian