Why do living things sleep? “Ask researchers this question, and listen as, like clockwork, a sense of awe and frustration creeps into their voices,” Veronique Greenwood wrote in 2018.

“In a way, it’s startling how universal sleep is,” she continued. “In the midst of the hurried scramble for survival, across eons of bloodshed and death and flight, uncountable millions of living things have laid themselves down for a nice, long bout of unconsciousness. This hardly seems conducive to living to fight another day … That such a risky habit is so common, and so persistent, suggests that whatever is happening is of the utmost importance.”

In other words, Greenwood writes, “whatever sleep gives to the sleeper is worth tempting death over and over again, for a lifetime.” Whatever sleep gives us is also worth the many hours, and large amounts of money, that humans now spend figuring out how to maximize our slumber. Sixty percent of America’s adults report experiencing sleep problems every night or most nights, Amanda Mull noted in 2019, and a variety of industries have sprung up to help us sleep longer and better.

Sleep is a need, but it’s also a ritual: Where we sleep, when we sleep, and who we sleep next to say a lot about who we are and what we want. Today’s reading list explores sleep as a scientific mystery, a physical need, and the most consistent routine of our daily lives.

Read the rest of this article at: The Atlantic

Balmoral Castle, in the Scottish Highlands, was Queen Elizabeth’s preferred resort among her several castles and palaces, and in the opening pages of “Spare” (Random House), the much anticipated, luridly leaked, and compellingly artful autobiography of Prince Harry, the Duke of Sussex, its environs are intimately described. We get the red-coated footman attending the heavy front door; the mackintoshes hanging on hooks; the cream-and-gold wallpaper; and the statue of Queen Victoria, to which Harry and his older brother, William, always bowed when passing. Beyond lay the castle’s fifty bedrooms—including the one known in the brothers’ childhood as the nursery, unequally divided into two. William occupied the larger half, with a double bed and a splendid view; Harry’s portion was more modest, with a bed frame too high for a child to scale, a mattress that sagged in the middle, and crisp bedding that was “pulled tight as a snare drum, so expertly smoothed that you could easily spot the century’s worth of patched holes and tears.”

It was in this bedroom, early in the morning of August 31, 1997, that Harry, aged twelve, was awakened by his father, Charles, then the Prince of Wales, with the terrible news that had already broken across the world: the princes’ mother, Princess Diana, from whom Charles had been divorced a year earlier and estranged long before that, had died in a car crash in Paris. “He was standing at the edge of the bed, looking down,” Harry writes of the moment in which he learned of the loss that would reshape his personality and determine the course of his life. He goes on to describe his father’s appearance with an unusual simile: “His white dressing gown made him seem like a ghost in a play.”

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

Santigold cemented her legacy as an alternative pop hero in the late 2000s thanks to her piercing artistic conviction. This September, following the release of her fourth album, Spirituals, she broke through to people again, but this time through her absence. Announcing the cancellation of her North American tour, Santigold shared a long statement that concluded, “I will not continue to sacrifice myself for an industry that has become unsustainable for, and uninterested in, the welfare of the artists it is built upon.”

Speaking on a video call a week later, she elaborated on the overarching impact of what have become untenable demands in music—anxiety, insomnia, fatigue, vertigo, and more—and the overlapping broken systems at their root. “The math does not ever work,” she said, referring not only to the grueling and increasingly unprofitable nature of touring, but to the broader reality for working musicians in an era where music has been devalued by exploitative streaming and ticketing models.

Within her statement, Santigold voiced what has become a central dilemma of musicians in a dysfunctional industry today: At all levels, from DIY acts to established indie icons and festival headliners, artists are suffering from mental health struggles vastly disproportionate from the general public—even in light of the mounting mental health crisis around the world.

Read the rest of this article at: Pitchfork

On the morning they were arrested for allegedly burning bodies as part of a series of Mafia murders, Marie-Josée Viau and Guy Dion had already finished breakfast and packed their daughter off to elementary school. A hand-drawn Mother’s Day card hung on the fridge next to family photographs. Viau, 44, didn’t have to go to her shift at the roadside poutine restaurant until later that day, so she tried baking something new: blueberry phyllo puffs. The pastries were still on the stove top when police arrived at 9:56 a.m. on October 16, 2019.

“We’re normal people,” Viau swore to the arresting officers, through her tears, after she and her husband were each charged with two counts of first-degree murder. “We didn’t kill anyone.”

Undercover recordings made by investigators told a different tale. The interception division of the Sûreté du Québec had secretly taped Viau and Dion speaking about how they’d disposed of bodies for members of the Calabrian Mafia. By their own admission, they’d incinerated corpses in their yard in a bonfire. “We did what we could with what we had,” she explained, when police questioned her about the cremations.

“But setting the bodies on fire?” a sergeant detective asked. “Was that [idea] from Guy, as he’s a fireman?”

Guy Dion was the tall, burly, 48-year-old fire chief of their small Quebec township. To make ends meet, he moonlighted for a paving company and refereed minor-league hockey games. His wife, Viau, worked as a cook and cashier at a fast-food chain called La Belle Province. Yearning for a way out of that dead-end job, she’d been taking online courses in business administration and freelancing as a building inspector. She had a hard face with sharp eyes and hair as long, dark, and wild as Dion’s was short, thin, and graying. The two lived in the countryside beyond Montreal, in the farming community of Saint-Jude (population 1,326), a village named after the patron saint of desperate cases. That’s precisely the higher power the couple needed when a dozen law enforcement vehicles converged on the property.

Before being taken away in an unmarked cruiser, a visibly shaking Viau requested a moment to switch outfits. She also wanted to know what would happen to their daughter when she got home from school. Officers informed her that childcare procedures were already under way. Outside the front window, the fall foliage had started changing color. The couple’s lawn, shrouded in dead leaves, was cordoned off with police tape. One maple tree stood out from the others, so red and orange that it seemed covered in flames.

Read the rest of this article at: Vanity Fair

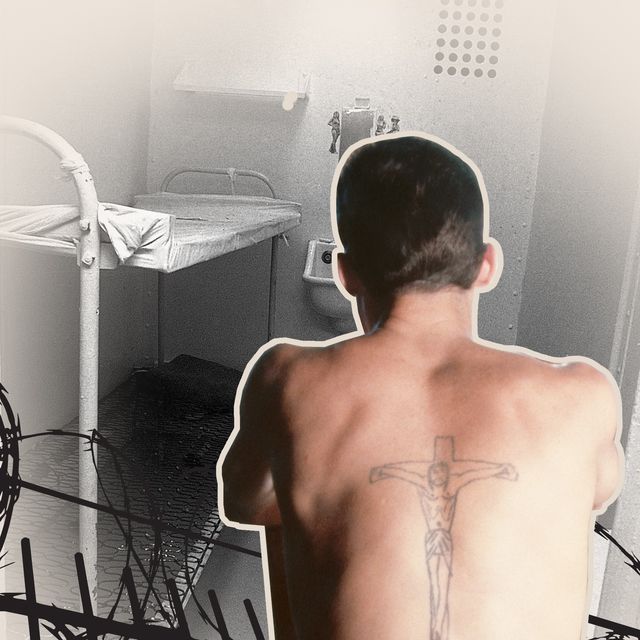

People who work, visit, and serve time at the notorious “House of Dead Men” never forget the horrors of their first day. Here, they tell Esquire about fighting for their lives behind bars.

There’s only one way to get on Rikers Island and one way to get off—a narrow, forty-two-hundred-foot-long bridge spanning a part of the East River. At the ribbon cutting in 1966, Mayor John Lindsay called it the “Bridge of Hope.” Forty years later, in 2006, the rapper Flavor Flav dubbed it the “Bridge of Pain.”

Purchased from the Rikers family in 1884 for $180,000 (about $5.1 million today), it began life in the nineteenth century as a motley assortment of jails and “workhouses,” or debtors’ prisons. Using fill from the construction of the Manhattan street grid, the city expanded the island from 87 acres to roughly 415 acres.

It was also a massive garbage dump. Residents of Hunts Point in the Bronx could smell it from their homes a mile away, and Upper East Siders could easily see the flames from the burning of mountains of trash. Enormous clouds of rats populated the dump to the point where they challenged dogs, and humans, for control of the island.

Even today, Rikers remains landfill to a depth of roughly ten feet, based on borings conducted in 2009. “They drilled a bunch of holes and all ten feet were garbage, mixed sand with pieces of glass and brick, pieces of wood—everything you can imagine that would be thrown away as materials from a construction site was in there,” explained Dr. Byron Stone, research geologist with the U.S. Geological Survey.

The first jail at Rikers, in the modern understanding of the place, was born in the spirit of reform. In July 1928, seven years after Vincent Gilroy’s broadside, the city fathers unveiled their plan for the Rikers Island Penitentiary. The New York Times described it as a model prison that would correct the evils of the past.

The inscription, placed in 1933, read, “Those who are laying this cornerstone today . . . hope that the treatment which these unfortunates will receive in this institution will be the means of salvaging some lives which would otherwise have been wasted.”

As the decades passed, this purported icon of penology became a forbidding place indeed. Detainees were thrown or jumped from the upper tiers to their deaths, so those floors had to be closed.

Violence ruled.

Read the rest of this article at: Esquire