Visions of “lost cities” in the jungle have consumed western imaginations since Europeans first visited the tropics of Asia, Africa and the Americas. From the Lost City of Z to El Dorado, a thirst for finding ancient civilisations and their treasures in perilous tropical forest settings has driven innumerable ill-fated expeditions. This obsession has seeped into western societies’ popular ideas of tropical forest cities, with overgrown ruins acting as the backdrop for fear, discovery and life-threatening challenges in countless films, novels and video games.

Throughout these depictions runs the idea that all ancient cities and states in tropical forests were doomed to fail. That the most resilient occupants of tropical forests are small villages of poison dart-blowing hunter-gatherers. And that vicious vines and towering trees – or, in the case of The Jungle Book, a boisterous army of monkeys – will inevitably claw any significant human achievement back into the suffocating green whence it came. This idea has been boosted by books and films that focus on the collapse of particularly enigmatic societies such as the Classic Maya. The decaying stone walls, the empty grand structures and the deserted streets of these tropical urban leftovers act as a tragic warning that our own way of life is not as secure as we would like to assume.

Read the rest of this article at: The Guardian

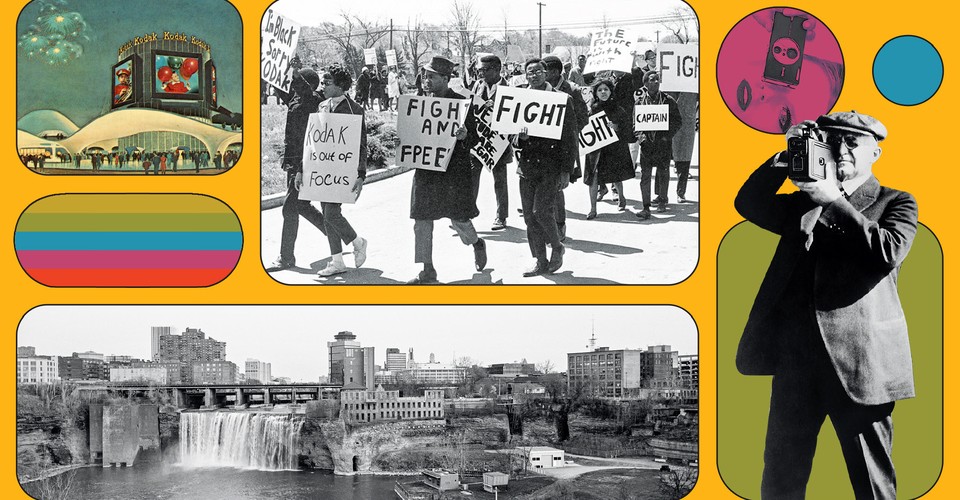

When I was in fifth grade, my class took a field trip to the George Eastman Museum, in Rochester, New York, as the fifth graders at my rural elementary school, 30 minutes south of the city, did every year. Housed in a Colonial Revival mansion built for the founder of the Eastman Kodak Company in 1905, the museum is home to one of the most significant photography and film collections in the world. But our job there was to stare at old cameras the size of our bodies, marvel at the luxury of having a pipe organ in your house, and write down what a daguerreotype is to prove that we’d been paying attention. At the end of the tour—in a second-story sitting room full of personal artifacts—we were presented, matter-of-factly, with a copy of Eastman’s suicide letter, dated March 14, 1932: “My work is done. Why wait?” Eastman shot himself in the heart with a Luger pistol at the age of 77.

Telling this story to a bunch of 10-year-olds was not meant to be morbid. It was meant to be edifying: To work is to live. And nobody could argue that Eastman hadn’t worked. His company, founded in 1880, invented the first easy-to-use consumer camera and thereby amateur photography; it achieved a near-monopoly on the consumer-film business, capturing the imagination of the entire world; it was Hollywood, and it was New York, and it was as grand as history—with a simple search, even a child can find images of Eastman hosting Thomas Edison, nonchalantly, in his backyard. The city where we stood was just another of his accomplishments: Eastman funded Rochester’s colleges and its hospital system, its cultural institutions, its nonprofits, its parks, its suburban housing developments. In 1920, his free pediatric dental clinic removed the tonsils of 1,470 children in seven weeks. Even in 2003, when I made that class trip, we were encouraged to believe we should feel lucky that he had chosen Rochester to lavish his attention upon.

Read the rest of this article at: The Atlantic

Last August, Alex Hernandez found herself in the market for a new piece of furniture.

Holed up in her Miami studio apartment, the 31-year-old executive assistant had grown weary of her “cheap and basic-looking” Ikea couch. She shopped around online and found a new one she liked — but it was a designer brand that was out of her price range.

So she opted for a makeover instead.

She spiced things up with a set of mid-century modern legs ($70) and a new cover ($120) from an Ikea customization website. The project cost Hernandez about one-tenth of the designer version she’d had her eye on and it saved an old piece of furniture from the landfill.

This type of upcycling, called Ikea hacking, has been on the rise during the pandemic.

And for companies that sell custom Ikea-friendly fixtures — legs, couch covers, knobs, and cabinet doors — business is booming.

Read the rest of this article at: the Hustle

In the summer of 1992, a 29-year-old Hungarian with political ambitions made his first visit to the US. For six weeks he toured the country with a coterie of young Europeans, all expenses paid by the German Marshall Fund, a thinktank devoted to transatlantic cooperation.

America had long fascinated Viktor Orbán, but he seemed disengaged and unaffected as the group walked around downtown Los Angeles, which was still reeling from the Rodney King riots two months earlier. One Dutch journalist on the trip recalled that the eastern Europeans in the group preferred to spend their daily stipends on “a Walkman and other electronics” rather than on food or fancy hotels. The free market and cutting-edge technologies certainly appealed more to Orbán than American debates and struggles over equality, justice or the rights of people of colour.

Orbán’s indifference to the plight of western minorities became more apparent during a tour of the Umatilla Indian Reservation in Oregon. Orbán and one of his travel companions, the Polish journalist Małgorzata Bochenek, listened to local complaints about economic injustice. He responded with questions about land distribution. Why didn’t the native tribes draft a strategy to monetise their common lands? After all, this was what Hungarian smallholders like his parents had been doing with local collective farms since the end of communism. Orbán began to sketch a business plan for the reservation, but when his Umatilla interlocutors didn’t respond with enthusiasm, he quickly lost interest.

What fascinated Orbán most during the rest of the trip was high politics. The group tour finished in New York City in July, where he attended the Democratic National Convention at Madison Square Garden and watched Bill Clinton’s nomination to the sounds of Fleetwood Mac’s Don’t Stop. The excitement of the occasion was not lost on Orbán. Visiting the US reaffirmed his own desire to become prime minister of Hungary.

At the time, the nature of the west’s appeal to young eastern Europeans was changing. In 1989, when Orbán studied at Oxford University on a Soros Foundation fellowship, the western consensus of the late cold war – deregulated capitalism, social stability, and national traditions – still held sway. These were the values he wanted to bring back to his home country. Three years later, by the time of his trip to the US, a shift was palpable. While free markets still reigned supreme, European and north American culture had moved into a more introspective mode. Orbán liked Clintonism as an approach to administration and economics, but had little interest in western human rights discourse, discussions of gender and race, or the legacies of colonialism and the Holocaust.

Read the rest of this article at: The Guardian