If you’re an overthinker, you’ll know exactly how it goes. A problem keeps popping up in your mind – for instance, a health worry or a dilemma at work – and you just can’t stop dwelling on it, as you desperately try to find some meaning or solution. Round and round the thoughts go but, unfortunately, the solutions rarely arrive.

In my daily work as a metacognitive clinical psychologist, I encounter many people who, in trying to find answers or meaning, or in attempting to make the right decision, spend most of their waking hours scrutinising their minds for solutions. Ironically, in this process of trying to figure out how to proceed in life, they come to a standstill.

When we spend too much time analysing our problems and dilemmas, we often end up more at a loss than we were to begin with. On top of that, persistent overthinking can result in a wide range of symptoms such as insomnia, trouble concentrating and loss of energy which, in turn, often leads to further worries regarding one’s symptoms, thereby creating a vicious cycle of overthinking. In some cases, this eventually leads to chronic anxiety or depression.

Read the rest of this article at: Psyche

Few things are more American than drinking heavily. But worrying about how heavily other Americans are drinking is one of them.

The Mayflower landed at Plymouth Rock because, the crew feared, the Pilgrims were going through the beer too quickly. The ship had been headed for the mouth of the Hudson River, until its sailors (who, like most Europeans of that time, preferred beer to water) panicked at the possibility of running out before they got home, and threatened mutiny. And so the Pilgrims were kicked ashore, short of their intended destination and beerless. William Bradford complained bitterly about the latter in his diary that winter, which is really saying something when you consider what trouble the group was in. (Barely half would survive until spring.) Before long, they were not only making their own beer but also importing wine and liquor. Still, within a couple of generations, Puritans like Cotton Mather were warning that a “flood of RUM” could “overwhelm all good Order among us.”

George Washington first won elected office, in 1758, by getting voters soused. (He is said to have given them 144 gallons of alcohol, enough to win him 307 votes and a seat in Virginia’s House of Burgesses.) During the Revolutionary War, he used the same tactic to keep troops happy, and he later became one of the country’s leading whiskey distillers. But he nonetheless took to moralizing when it came to other people’s drinking, which in 1789 he called “the ruin of half the workmen in this Country.”

Hypocritical though he was, Washington had a point. The new country was on a bender, and its drinking would only increase in the years that followed. By 1830, the average American adult was consuming about three times the amount we drink today. An obsession with alcohol’s harms understandably followed, starting the country on the long road to Prohibition.

Read the rest of this article at: The Atlantic

When trying to explain what motivates me as a physicist, the film A Passage to India (1984) comes to mind. Based on the play by Santha Rama Rau, adapted from the novel by E M Forster, it describes the fallout from a rape case in the fictional city of Chandrapore, during the British Raj in India in the 1920s. What keeps the viewer’s attention is the subtlety of the relationships between the characters – particularly the fragile friendship between the man accused of the rape, Dr Aziz, and an Englishman, Mr Fielding. Data about identity alone, such as race, class, gender or educational status, can never reveal these dynamics nor capture why they fascinate us. When the case arrives in court, ostensibly similar people behave very differently in relation to the defendant. The dynamics of individual behaviour trump any immutable labels we might apply; yet these static labels also impose constraints on just how far any individual can go. We watch, we theorise, and we update our knowledge of the characters and the forces at work. By the end, we find that Fielding and Aziz are more alike than we’d thought, having created a new bond on the basis of a more complete understanding of one another.

Read the rest of this article at: aeon

Follow us on Instagram @thisisglamorous

[instagram-feed]

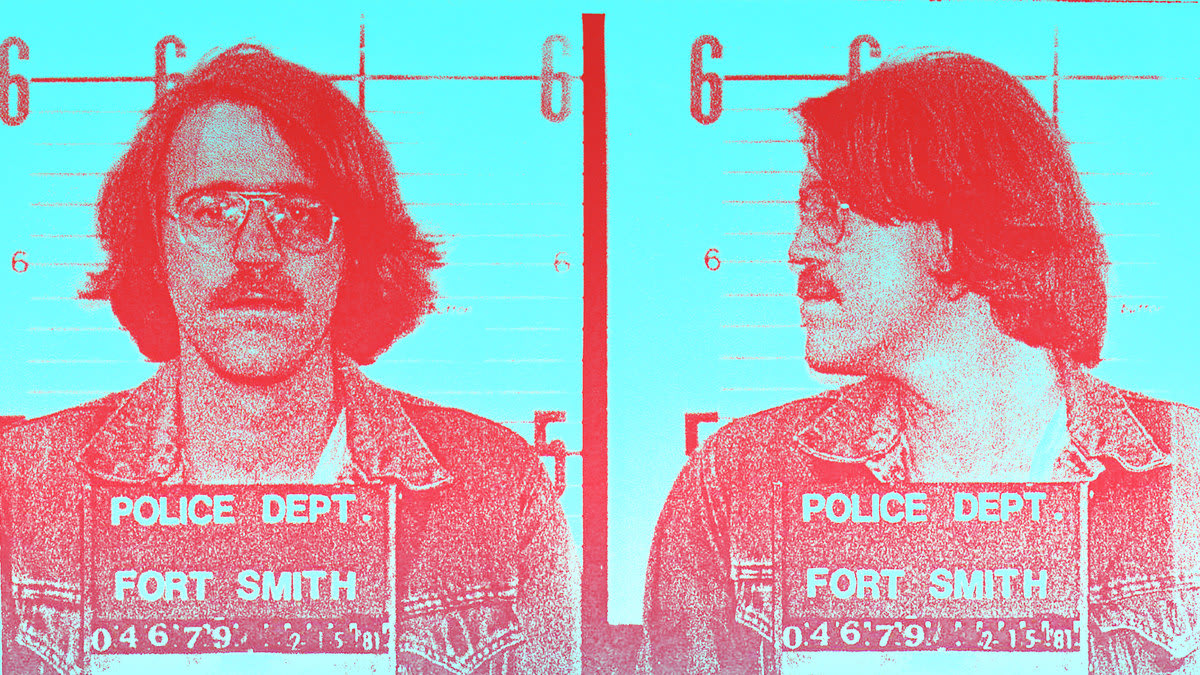

On a Sunday night in February 1981, Rolf Kaestel robbed an Arkansas taco restaurant using a toy water gun. No one was injured in the stickup. He stole $264—and was sentenced to life in prison.

Forty years later, Kaestel is still behind bars for aggravated robbery. His penalty is unusually severe, supporters say, for a crime without injuries or even a physical altercation.

This year could be the 70-year-old inmate’s final shot at redemption, a taste of freedom for however many good years he has left. Kaestel’s fate now rests in the hands of Republican Gov. Asa Hutchinson, who denied him clemency in 2015 and is expected to decide on his latest application any day now. Should Kaestel be rejected again, he must wait four more years to reapply to the Arkansas Parole Board, which will again send its recommendation to the governor. Under state law, inmates with life sentences aren’t eligible for parole unless the governor commutes their sentence.

But no one, not even the former prosecutor in the case, is demanding that Kaestel remain behind bars. Since 2012, the parole board recommended clemency three times, but Hutchinson and his predecessor Mike Beebe declined to grant it. The victim of the crime, Dennis Schluterman, has spent years pleading for Kaestel’s release. “It’s time for his break to come. He needs to be set free,” Schluterman said in a video recorded outside the Arkansas State Capitol and delivered to Beebe’s office in 2013. “And if you really want to know, I believe that the state owes him. I know you wouldn’t see it that way, but this man has paid the price 10 times over, and it’s time, it’s time for you to let him go.”

“You can see how upset I’m getting right now,” Schluterman added, visibly distraught and his voice wavering. “Many nights I’ve been the same way. I just don’t feel like Rolf should have to spend another day in prison.”

In an interview with The Daily Beast, Schluterman said the same. “It’s not right, is all I want people to know and, if possible, to stand up and support us to help him get out.” Schluterman added, “His life’s running out. His time is running out. God, give him a little bit of something. It wasn’t that bad of a crime to be doing that kind of time.”

Kaestel and his supporters are bewildered that the state of Arkansas insists on keeping the aging inmate imprisoned at a cost of more than $20,000 a year—first at the infamous Cummins Unit, then in Utah under an interstate compact—when prisoners accused of more violent offenses are treated more leniently. “I have not been able to make any sense of it,” Kaestel told The Daily Beast in a letter, “not because it’s me or my case but because this kind of thing should not happen anywhere to anyone.”

He’s had a single visitor in the past 22 years: Colby Frazier, a former reporter for Salt Lake City Weekly. Frazier’s 2014 profile called Kaestel “invisible to those who put him there and a mystery of sorts to those who store him,” referring to prison officials in both states punting questions about Kaestel to the other. Kaestel, the writer said, stumbled into “a volatile corner of the justice system—the part that doesn’t rely so much on concrete law, but more on the whims and moods of the human beings who pull the levers.”

“He was actually very calm and collected and casually got the money and handed it to me when I then asked him to do so. And, I turned and left. There were no overt threats or acts. It was over in a few seconds.”

Read the rest of this article at: The Daily Beast