Dear readers,

We’re gradually migrating this curation feature to our Weekly Newsletter. If you enjoy these summaries, we think you’ll find our Substack equally worthwhile.

On Substack, we take a closer look at the themes from these curated articles, examine how language shapes reality and explore societal trends. Aside from the curated content, we continue to explore many of the topics we cover at TIG in an expanded format—from shopping and travel tips to music, fashion, and lifestyle.

If you’ve been following TIG, this is a chance to support our work, which we greatly appreciate.

Thank you,

the TIG Team

Why did Kamala Harris lose the election? So glad you asked. Pull up a chair—actually, no need to sit, because the answer is so simple that it can be summed up in a few seconds. The main problem was the incumbency disadvantage, exacerbated by inflation—and immigration, and also urban disorder, wokeness, and trans swimmers. Also, Joe Biden dropped out too late, and Harris peaked too early, and the Democrats should have picked another candidate, or maybe they should have stuck with Biden. Donald Trump’s voters were motivated by white grievance, except for the people of color who were motivated by economic anxiety; ultimately, the main issue was the patriarchy, exacerbated by misinformation on long-form podcasts, although of course Harris should have gone on Rogan. From now on, the Democratic Party has no choice but to move left, move right, overhaul its approach entirely, and/or change nothing at all.

A few days after the election, Musa al-Gharbi, a forty-one-year-old sociologist at Stony Brook University, published a lengthy piece on Substack called “A Graveyard of Bad Election Narratives,” using bar charts and cross tabs to “rule out what wasn’t the problem”: sexism, racism, third-party spoilers. “It didn’t take me long to write, because I realized I’d written essentially the same piece after the 2020 election, and also after the 2016 election,” he said the other afternoon, at a diner in Greenwich Village, while finishing off a black coffee and a plate of fries. “The details change, of course, but the basic trends have been consistent for a long time.” Harris didn’t do herself any favors, he argued—she was “unwilling or unable to distance herself from the unpopular incumbent,” she shouldn’t have campaigned with Liz Cheney, and so on—but any Democrat would have had a hard time winning, because, during the past three decades, “Democrats have become the party of élites,” alienating increasing numbers of “normie voters” in the process.

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

As winter descended on San Francisco in late 2022, OpenAI quietly pushed a new service dubbed ChatGPT live with a blog post and a single tweet from CEO Sam Altman. The team labeled it a “low-key research preview” — they had good reason to set expectations low.

“It couldn’t even do arithmetic,” Liam Fedus, OpenAI’s head of post-training says. It was also prone to hallucinating or making things up, adds Christina Kim, a researcher on the mid-training team.

Ultimately, ChatGPT would become anything but low-key.

While the OpenAI researchers slept, users in Japan flooded ChatGPT’s servers, crashing the site only hours after launch. That was just the beginning.

“The dashboards at that time were just always red,” recalls Kim. The launch coincided with NeurIPS, the world’s premier AI conference, and soon ChatGPT was the only thing anyone there could talk about. ChatGPT’s error page — “ChatGPT is at capacity right now” — would become a familiar sight.

“We had the initial launch meeting in this small room, and it wasn’t like the world just lit on fire all of a sudden,” Fedus says during a recent interview from OpenAI’s headquarters. “We’re like, ‘Okay, cool. I guess it’s out there now.’ But it was the next day when we realized — oh, wait, this is big.”

“The dashboards at that time were just always red.”

Two years later, ChatGPT still hasn’t cracked advanced arithmetic or become factually reliable. It hasn’t mattered. The chatbot has evolved from a prototype to a $4 billion revenue engine with 300 million weekly active users. It has shaken the foundations of the tech industry, even as OpenAI loses money (and cofounders) hand over fist while competitors like Anthropic threaten its lead.

Whether used as praise or pejorative, “ChatGPT” has become almost synonymous with generative AI. Over a series of recent video calls, I sat down with Fedus, Kim, ChatGPT head of product Nick Turley, and ChatGPT engineering lead Sulman Choudhry to talk about ChatGPT’s origins and where it’s going next.

ChatGPT was effectively born in December 2021 with an OpenAI project dubbed WebGPT: an AI tool that could search the internet and write answers. The team took inspiration from WebGPT’s conversational interface and began plugging a similar interface into GPT-3.5, a successor to the GPT-3 text model released in 2020. They gave it the clunky name “Chat with GPT-3.5” until, in what Turley recalls as a split-second decision, they simplified it to ChatGPT.

The name could have been the even more straightforward “Chat,” and in retrospect, he thinks perhaps it should have been. “The entire world got used to this odd, weird name, we’re probably stuck with it. But obviously, knowing what I know now, I wish we picked a slightly easier to pronounce name,” he says. (It was recently revealed that OpenAI purchased the domain chat.com for more than $10 million of cash and stock in mid-2023.)

As the team discovered the model’s obvious limitations, they debated whether to narrow its focus by launching a tool for help with meetings, writing, or coding. But OpenAI cofounder John Schulman (who has since left for Anthropic) advocated for keeping the focus broad.

The team describes it as a risky bet at the time; chatbots were viewed as an unremarkable backwater of machine learning, they thought, with no successful precedents. Adding to their concerns, Facebook’s Galactica AI bot had just spectacularly flamed out and been pulled offline after generating false research.

Read the rest of this article at: The Verge

A few weeks ago, I wrote about happiness and music but didn’t mention perhaps the most famously joyful work ever written: Ludwig van Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, composed in 1824, which ends with the famous anthem “Ode to Joy,” based on Friedrich Schiller’s poem “An die Freude.” In the symphony’s fourth movement, with the orchestra playing at full volume, a huge choir belts out these famous lyrics: “Freude, schöner Götterfunken / Tochter aus Elysium / Wir betreten feuertrunken / Himmlische, dein Heiligtum!” In English: “Joy, thou shining spark of God / Daughter of Elysium / With fiery rapture, goddess / We approach thy shrine!”

You might assume that Beethoven, whose 254th birthday classical-music fans will celebrate this coming week, was a characteristically joyful man. You would be incorrect in that assumption. He was well known among his contemporaries as an irascible, melancholic, hypercritical grouch. He never sustained a romantic relationship that led to marriage, was mercurial in his friendships, and was sly about his professional obligations.

Read the rest of this article at: The Atlantic

The American industrialist and financier John Pierpont Morgan (1837-1913) was a serious collector of objects, books, and ephemera for most of his life, and his avidity and the diversity of the materials he acquired—from pages of a fourteenth-century Iraqi Quran to the original manuscript of Charles Dickens’s “A Christmas Carol”—are a testament to both his American determinism and his wide-ranging tastes. One of the founders of U.S. Steel, and a key figure in the creation of General Electric, Morgan, who helped President Grover Cleveland avert a national financial disaster, in 1895, by defending the gold standard, didn’t have much patience for those who felt there were things that couldn’t get done. Jean Strouse, in her extraordinary, definitive biography “Morgan: American Financier” (1999), describes a man whose physical attributes (broad shoulders, penetrating gaze), febrile mind, and seemingly inexhaustible energy became synonymous with the outsized, overstuffed Gilded Age.

Although he left no comprehensive statement about his passion for collecting, I think that, like most students of art, Morgan collected as a way of dreaming through the dreams of others—the artists and artisans who produced the powerful works he bought, including Byzantine enamels, Italian Renaissance paintings, three Gutenberg Bibles, and an autographed manuscript of Mark Twain’s “Pudd’nhead Wilson,” purchased directly from the author. Like the legendary collectors William Randolph Hearst and Andy Warhol, Morgan was self-conscious about some of his physical qualities: he suffered from rosacea, which got worse as he aged. The beauty of art was something to hide behind. And it could be nourishing to his countrymen, too. Morgan was the president of the Metropolitan Museum of Art from 1904 until his death, and he knew that the works he acquired on his trips to Europe and North Africa could expand America’s understanding of art and history, and thus enrich its aesthetic future.

Its employees are some of its most devoted congregants. “It is the best of the old internet, and it’s the best of old San Francisco, and neither one of those things really exist in large measures anymore,” says the Internet Archive’s director of library services, Chris Freeland, another longtime staffer, who loves cycling and favors black nail polish. “It’s a window into the late-’90s web ethos and late-’90s San Francisco culture—the crunchy side, before it got all tech bro. It’s utopian, it’s idealistic.”

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

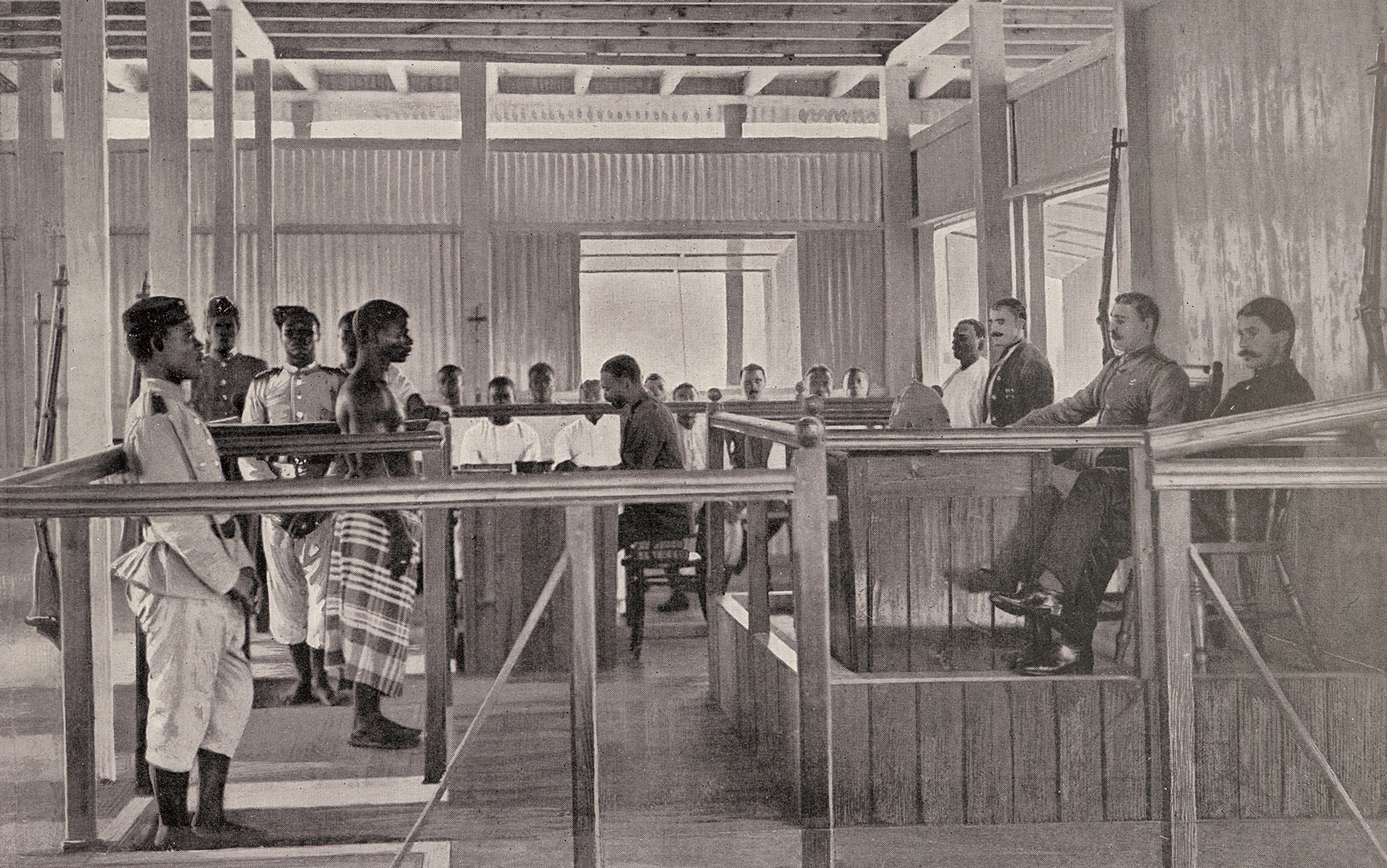

Law was central to the British colonial project to subjugate the colonised populations and maximise their exploitation. Convinced of its superiority, British forces sought to exchange their law for the maximum extraction of resources from the colonised territories. In The Dual Mandate in British Tropical Africa (1922), F D Lugard – the first governor general of Nigeria (previously governor of Hong Kong) – summed up the advantages of European colonialism as:

Europe benefitted by the wonderful increase in the amenities of life for the mass of her people which followed the opening up of Africa at the end of the 19th century. Africa benefited by the influx of manufactured goods, and the substitution of law and order for the methods of barbarism.

Lugard, here, expresses the European orthodoxy that colonised territories did not contain any Indigenous laws before the advent of colonialism. In its most extreme form, this erasure manifested as a claim of terra nullius – or nobody’s land – where the coloniser claimed that the Indigenous population lacked any form of political organisation or system of land rights at all. So, not only did the land not belong to any individual, but the absence of political organisation also freed the coloniser from the obligation of negotiating with any political leader. Europeans declared vast territories – and, in the case of Australia, a whole continent – terra nullius to facilitate colonisation. European claims of African ‘backwardness’ were used to justify the exclusion of Africans from political decision-making. In the 1884-85 Berlin Conference, for example, 13 European states (including Russia and the Ottoman Empire) and the United States met to divide among themselves territories in Africa, transforming the continent into a conceptual terra nullius. This allowed for any precolonial forms of law to be disregarded and to be replaced by colonial law that sought to protect British economic interests in the colonies.

In other colonies, such as India, where some form of precolonial law was recognised, by using a self-referential and Eurocentric definition of what constituted law, the British were able to systematically replace Indigenous laws. This was achieved by declaring them to be repugnant or by marginalising such laws to the personal sphere, ie, laws relating to marriage, succession and inheritance, and hence applicable only to the colonised community. Indigenous laws that Europeans allowed to continue were altered beyond recognition through colonial interventions.

The rule of law was central both to the colonial legal enterprise and to the British imagination of itself as a colonial power. Today, the doctrine of the rule of law is closely associated with the works of the British jurist A V Dicey (1835-1922) who articulated the most popular modern idea of the rule of law at the end of the 19th century. The political theorist Judith Shklar in 1987 described Dicey’s work as ‘an unfortunate outburst of Anglo-Saxon parochialism’, in part because he identified the doctrine as being embedded within the English legal tradition and argued that the supremacy of law had been a characteristic of the English constitution ever since the Norman conquest. In his germinal Introduction to the Study of the Law of the Constitution (1889), Dicey noted three key features of the rule of law: firstly, the absence of arbitrary powers of the state; secondly, legal equality among people of all classes; and, lastly, that the general principles of constitutional law had developed as part of English common law, rather than being attributed to a written constitution.

Read the rest of this article at: Aeon

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25782636/247422_ChatGPT_anniversary_CVirginia.jpg)