Dear readers,

We’re gradually migrating this curation feature to our Weekly Newsletter. If you enjoy these summaries, we think you’ll find our Substack equally worthwhile.

On Substack, we take a closer look at the themes from these curated articles, examine how language shapes reality and explore societal trends. Aside from the curated content, we continue to explore many of the topics we cover at TIG in an expanded format—from shopping and travel tips to music, fashion, and lifestyle.

If you’ve been following TIG, this is a chance to support our work, which we greatly appreciate.

Thank you,

the TIG Team

“You are the media now.” That’s the message that began to cohere among right-wing influencers shortly after Donald Trump won the election this week. Elon Musk first posted the phrase, and others followed. “The legacy media is dead. Hollywood is done. Truth telling is in. No more complaining about the media,” the right-wing activist James O’Keefe posted shortly after. “You are the media.”

It’s a particularly effective message for Musk, who spent $44 billion to purchase a communications platform that he has harnessed to undermine existing media institutions and directly support Trump’s campaign. QAnon devotees also know the phrase as a rallying cry, an invitation to participate in a particular kind of citizen “journalism” that involves just asking questions and making stuff up altogether.

“You are the media now” is also a good message because, well, it might be true.

A defining quality of this election cycle has been that few people seem to be able to agree on who constitutes “the media,” what their role ought to be, or even how much influence they have in 2024. Based on Trump’s and Kamala Harris’s appearances on various shows—and especially Trump’s and J. D. Vance’s late-race interviews with Joe Rogan, which culminated in the popular host’s endorsement—some have argued that this was the “podcast election.” But there’s broad confusion over what actually moves the needle. Is the press the bulwark against fascism, or is it ignored by a meaningful percentage of the country? It is certainly beleaguered by a conservative effort to undermine media institutions, with Trump as its champion and the fracturing caused by algorithmic social media. It can feel existential at times competing for attention and reckoning with the truth that many Americans don’t read, trust, or really care all that much about what papers, magazines, or cable news have to say.

Read the rest of this article at: The Atlantic

It isn’t every day that psychologists identify a hot new character archetype. Human design doesn’t usually generate media stories about “the most-talked-about personality trait for autumn/winter”. And yet, something close to this is unfolding with the current fascination with so-called “dark empaths”.

On TikTok, the term has been trending, with more than 2.6m mentions. There’s even a #darkempathtok hashtag, all the better to locate the latest videos with ominous titles such as “When an empath goes dark” and “The most DANGEROUS personality”. A measure of how far the idea has travelled is that, when I mentioned the phrase to my hairdresser, he helpfully explained: “Oh yes, they’re the ones who are like narcissists, only more devious.”

Dark empaths were first identified in a 2021 study published in the journal Personality and Individual Differences. Researchers defined it as “a novel psychological construct” concerning individuals who have a high degree of empathy alongside what’s known as “dark traits”. How this plays out in practice is someone who appears to be caring and sensitive, but who is actually using those skills to further their own agenda.

But how is it possible to manufacture empathy? Can’t we as humans detect when that is being done? It turns out there is more than one type of empathy. The deeply caring type most of us understand is called “affective empathy” – the real thing. “It is the degree to which I feel what you are feeling,” says Nadja Heym, co-author of the research study and associate professor in personality psychology and psychopathology at Nottingham Trent University. “So, for example, when you feel sad, that makes me feel sad. But there’s another type known as cognitive empathy. In that case, the script is: ‘I know what you’re thinking. I understand your mental state. But I really don’t care about it.’ And this information is important to the dark empath because, if they want to predict your behaviour, they need to understand what you’re thinking in order to try to control you.” It is this manipulation by stealth that can feel so unnerving if you are on the receiving end of it.

Yasmin works in event management. “It was a very social vibe and Elaine, the new boss, liked to treat us to a Friday afternoon ‘drinks trolley’, AKA a few bottles of fizz being passed around the desks. The evening would often end in the pub.” Soon, her boss started to share confidences about her personal life, prompting Yasmin to reveal her struggles in trying to get pregnant. “It felt great that my boss was also becoming a good friend and mentor, and made office life enjoyable.”

Things started to go wrong when Elaine confided about how stress was taking its toll on her health. She frequently asked Yasmin to take on extra tasks. “I was happy to help her out knowing what pressure she was under from management. She had also hinted a promotion was in the offing for me. But then she embarked upon a not-so-subtle campaign to try to put me off the idea of starting a family. She’d tell me that, at 35, I still had loads of time, and didn’t I want to prioritise my career and future earnings first? It’s only with hindsight that I realise what an outrageous boundary overstep this was. At the time, I genuinely thought she was looking out for me.”

Read the rest of this article at: The Guardian

They Searched Through Hundreds of Bands to Solve an Online Mystery

For years, a small but heavily engaged community has gathered online, entirely dedicated to the goal of identifying a single elusive song. On Monday, following an exhaustive search, they announced they’d found it.

Now that “The Most Mysterious Song on the Internet” has been located, it leaves behind an entire subculture of “lostwave” music that stretches from cassette tapes to Spotify. Even amid their success, many investigators are unsure about what happens to the community now that its goal has been achieved. What happens to lost media once it’s been found?

We now know the song in question is called “Subways of Your Mind” by FEX, but until Monday, it had lived up to its sobriquet for 17 years. The song was recorded off the German radio station NDR in the early ’80s and was just a question mark on a cassette case until 2007, when it was digitized and posted to various Usenet newsgroups and music forums along with requests for the internet’s help in identifying the track. No one knew what it was.

Read the rest of this article at: Wired

The wreck was like a bug on the wall, a jumbly shape splayed on the abyssal plain. It was noticed by a team of autonomous-underwater-vehicle operators on board a subsea exploration vessel, working at an undisclosed location in the Atlantic Ocean, about a thousand miles from the nearest shore. The analysts belonged to a small private company that specializes in deep-sea search operations; I have been asked not to name it. They were looking for something else. In the past decade, the company has helped to transform the exploration of the seabed by deploying fleets of A.U.V.s—underwater drones—which cruise in formation, mapping large areas of the ocean floor with high-definition imagery.

“We find wrecks everywhere, just blunder into them,” Mensun Bound, a maritime archeologist who works frequently with the company, told me. The pressures of time and money mean that it is usually not possible to stop. (Top-of-the-line search vessels can cost about a hundred and fifty thousand dollars a day to charter.) “Sometimes it’s heartbreaking,” Bound said. A few years ago, he was with a team that stumbled across a wreck in the Indian Ocean. They had a few hours to spare, so they brought a sodden box up to the surface. It was full of books. “That was the most exciting thing I’ve ever found in my life,” Bound said. “But then the question becomes: What do we do with it?” The seabed is a complicated, as well as an expensive, place to operate in. So they put it back.

This Atlantic wreck was beguiling. An R.O.V.—a remotely operated vehicle, connected by a cable to the exploration vessel—was sent down to take a closer look. It was the remains of an old wooden sailing ship, stuffed with cargo, lying some six thousand metres below the surface—much deeper than the Titanic. The contents seemed to be Asian in origin: intricate lacquered screens and bolts of cloth, thousands of slender rattan canes, and an extraordinary array of porcelain, all preserved in the darkness of the ocean. “It was just cascading in these spills down around the slopes and undulations of the seabed,” Bound recalled. “And there were barrels there, which hadn’t been opened. They were sitting there intact.”

There is something almost dangerously tantalizing about an undiscovered shipwreck. It exists on the edge of the real, containing death and desire. Lost ships are lost knowledge, waiting to be regained. “It’s like popping the locks on an old suitcase and you lift the lid,” Bound told me. Bound grew up on the Falkland Islands in the nineteen-fifties. In 2022, he found the Endurance, Ernest Shackleton’s polar-exploration ship, under the ice of the Weddell Sea, off Antarctica. “On a shipwreck, everything, in theory, that was there on that ship when it went down is still there,” he said. “It’s all the product of one unpremeditated instant of time.”

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

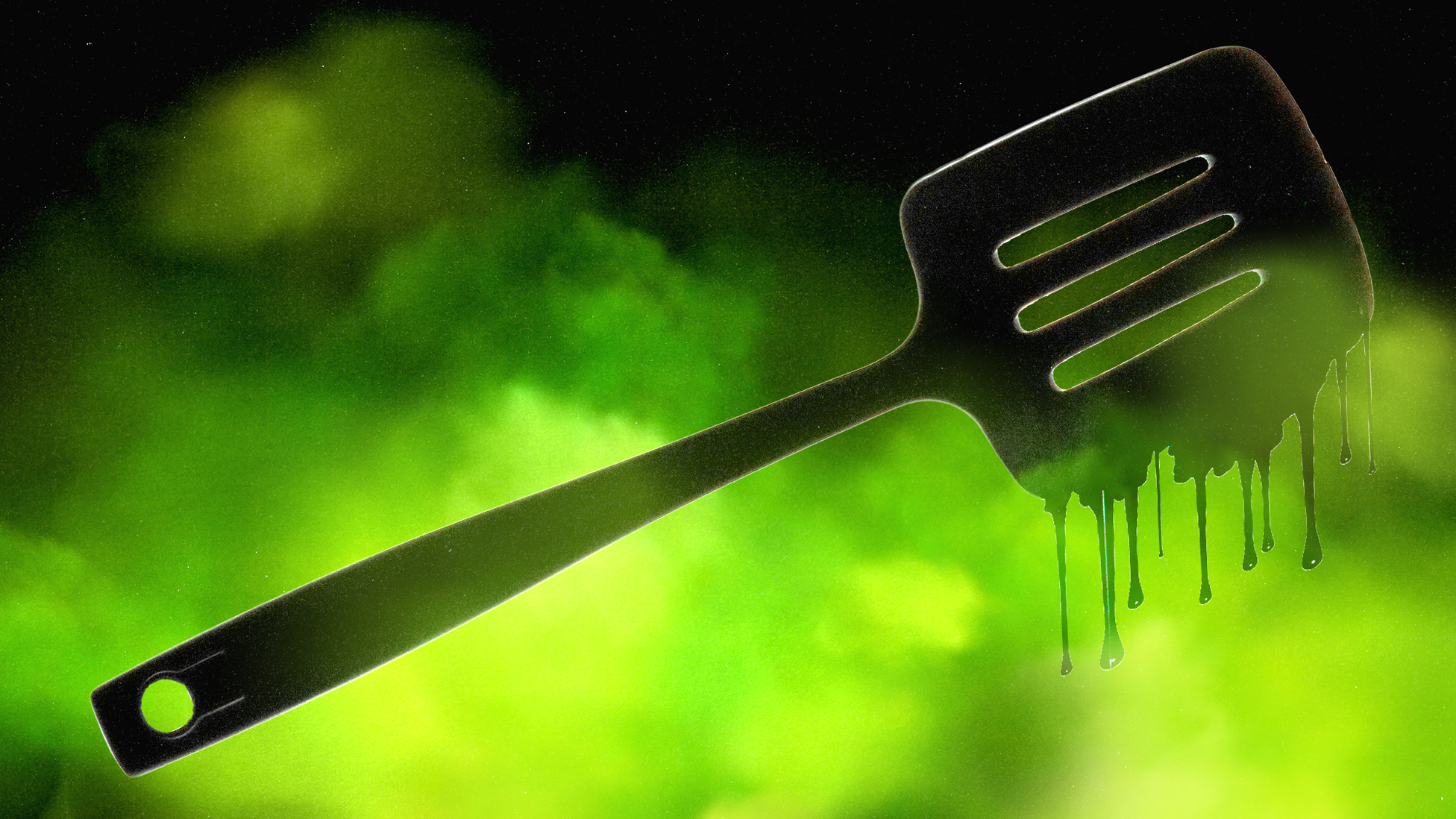

For the past several years, I’ve been telling my friends what I’m going to tell you: Throw out your black plastic spatula. In a world of plastic consumer goods, avoiding the material entirely requires the fervor of a religious conversion. But getting rid of black plastic kitchen utensils is a low-stakes move, and worth it. Cooking with any plastic is a dubious enterprise, because heat encourages potentially harmful plastic compounds to migrate out of the polymers and potentially into the food. But, as Andrew Turner, a biochemist at the University of Plymouth recently told me, black plastic is particularly crucial to avoid.

In 2018, Turner published one of the earliest papers positing that black plastic products were likely regularly being made from recycled electronic waste. The clue was the plastic’s concerning levels of flame retardants. In some cases, the mix of chemicals matched the profile of those commonly found in computer and television housing, many of which are treated with flame retardants to prevent them from catching fire.

Because optical sensors in recycling facilities can’t detect them, black-colored plastics are largely rejected from domestic-waste streams, resulting in a shortage of black base material for recycled plastic. So the demand for black plastic appears to be met “in no insignificant part” via recycled e-waste, according to Turner’s research. TV and computer casings, like the majority of the world’s plastic waste, tend to be recycled in informal waste economies with few regulations and end up remolded into consumer products, including ones, such as spatulas and slotted spoons, that come into contact with food.

You simply do not want flame retardants anywhere near your stir-fry. Flame retardants are typically not bound to the polymers to which they are added, making them a particular flight risk: They dislodge easily and make their way into the surrounding environment. And, indeed, another paper from 2018 found that flame retardants in black kitchen utensils readily migrate into hot cooking oil. The health concerns associated with those chemicals are well established: Some flame retardants are endocrine disruptors, which can interfere with the body’s hormonal system, and scientific literature suggests that they may be associated with a range of ailments, including thyroid disease, diabetes, and cancer. People with the highest blood levels of PBDEs, a class of flame retardants found in black plastic, had about a 300 percent increase in their risk of dying from cancer compared with people who had the lowest levels, according to a study released this year. In a separate study, published in a peer-reviewed journal this month, researchers from the advocacy group Toxic-Free Future and from Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam found that, out of all of the consumer products they tested, kitchen utensils had some of the highest levels of flame retardants.

Read the rest of this article at: The Atlantic