Dear readers,

We’re gradually migrating this curation feature to our Weekly Newsletter. If you enjoy these summaries, we think you’ll find our Substack equally worthwhile.

On Substack, we take a closer look at the themes from these curated articles, examine how language shapes reality and explore societal trends. Aside from the curated content, we continue to explore many of the topics we cover at TIG in an expanded format—from shopping and travel tips to music, fashion, and lifestyle.

If you’ve been following TIG, this is a chance to support our work, which we greatly appreciate.

Thank you,

the TIG Team

Last spring, a graduate student in social anthropology—let’s call him Chris—sat down at his laptop and asked ChatGPT for help with a writing assignment. He pasted a few thousand words, a mix of rough summaries and jotted-down bullet points, into the text box that serves as ChatGPT’s interface. “Here’s my entire exam,” he wrote. “Don’t edit it, I will tell you what to do after you’ve read it.”

Chris was tackling a difficult paper about perspectivism, which is the anthropological principle that one’s perspective inevitably shapes the observations one makes and the knowledge one acquires. ChatGPT asked him, “What specific tasks or assistance do you need with this content?” Chris pasted one paragraph from his draft into the text box. “Please edit it,” he typed.

ChatGPT returned a condensed and slightly reworded version of the paragraph. The tweaked version removed the French term grande idée and Americanized the British spelling of “marginalization,” but otherwise wasn’t obviously better. Soon, Chris gave up on getting ChatGPT to edit his work. Instead, he outlined a passage that he wanted to add to the paper. “Please write this paragraph as you deem fit,” he instructed.

The response was stilted. “I want the language to be alive yet direct and to the point,” he typed. But the result still wasn’t quite right. He told ChatGPT: “I like this, but write it slightly more as a story. Don’t overdo it.”

In the course of an hours-long exchange, Chris came to realize that ChatGPT’s writing wasn’t up to his standards. He tried other approaches. At one point, he shared the text of a relevant book chapter and, in a sort of Socratic dialogue with the model, asked a string of questions: “Can you give an example that illustrates this?” “What do you think it refers to?” “Could you give an illustrative example with myth instead?” Later, Chris asked the A.I.’s opinion about the strength of a paragraph he had written. “Can you put this argument to the test? Is it true, in your analysis?”

When ChatGPT came out, many people deemed it a perfect plagiarism tool. “AI seems almost built for cheating,” Ethan Mollick, an A.I. commentator, wrote in his book “Co-Intelligence.” (He later predicted a “homework apocalypse.”) An agricultural-science professor at Texas A&M failed all his students when he became convinced that the whole class had used A.I. to write their assignments. (It turned out that his method of detection—asking ChatGPT whether it had generated the papers in question—was unreliable, so he changed the grades.) A columnist in The Spectator asked, “How can you send students home with essay assignments when, between puffs of quasi-legal weed, they can tell their laptop: ‘Hey, ChatGPT, write a good 1,000-word paper comparing the themes of Fleabag and Macbeth’—and two seconds later, voila?”

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

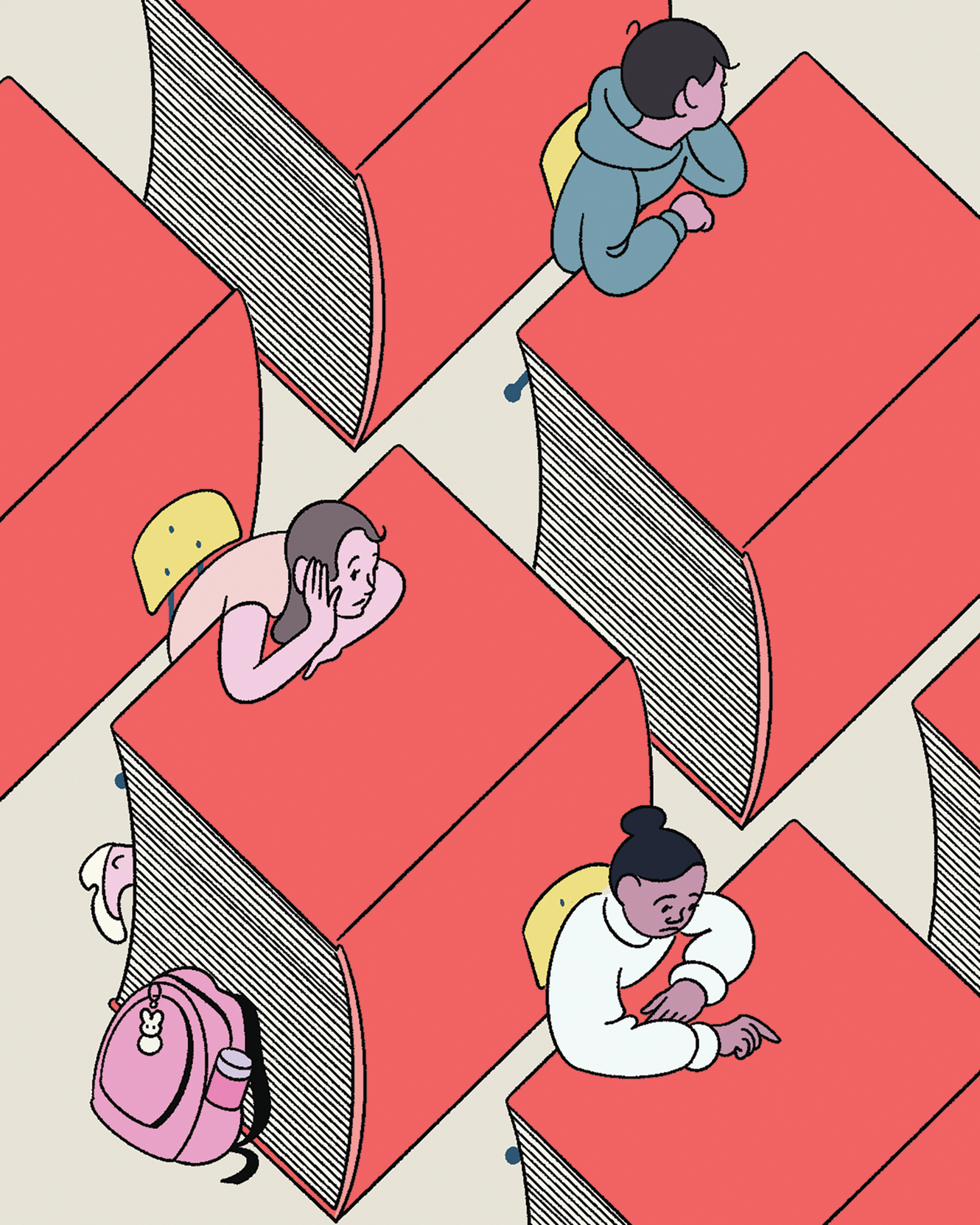

Nicholas Dames has taught Literature Humanities, Columbia University’s required great-books course, since 1998. He loves the job, but it has changed. Over the past decade, students have become overwhelmed by the reading. College kids have never read everything they’re assigned, of course, but this feels different. Dames’s students now seem bewildered by the thought of finishing multiple books a semester. His colleagues have noticed the same problem. Many students no longer arrive at college—even at highly selective, elite colleges—prepared to read books.

This development puzzled Dames until one day during the fall 2022 semester, when a first-year student came to his office hours to share how challenging she had found the early assignments. Lit Hum often requires students to read a book, sometimes a very long and dense one, in just a week or two. But the student told Dames that, at her public high school, she had never been required to read an entire book. She had been assigned excerpts, poetry, and news articles, but not a single book cover to cover.

“My jaw dropped,” Dames told me. The anecdote helped explain the change he was seeing in his students: It’s not that they don’t want to do the reading. It’s that they don’t know how. Middle and high schools have stopped asking them to.

In 1979, Martha Maxwell, an influential literacy scholar, wrote, “Every generation, at some point, discovers that students cannot read as well as they would like or as well as professors expect.” Dames, who studies the history of the novel, acknowledged the longevity of the complaint. “Part of me is always tempted to be very skeptical about the idea that this is something new,” he said.

And yet, “I think there is a phenomenon that we’re noticing that I’m also hesitant to ignore.” Twenty years ago, Dames’s classes had no problem engaging in sophisticated discussions of Pride and Prejudice one week and Crime and Punishment the next. Now his students tell him up front that the reading load feels impossible. It’s not just the frenetic pace; they struggle to attend to small details while keeping track of the overall plot.

No comprehensive data exist on this trend, but the majority of the 33 professors I spoke with relayed similar experiences. Many had discussed the change at faculty meetings and in conversations with fellow instructors. Anthony Grafton, a Princeton historian, said his students arrive on campus with a narrower vocabulary and less understanding of language than they used to have. There are always students who “read insightfully and easily and write beautifully,” he said, “but they are now more exceptions.” Jack Chen, a Chinese-literature professor at the University of Virginia, finds his students “shutting down” when confronted with ideas they don’t understand; they’re less able to persist through a challenging text than they used to be. Daniel Shore, the chair of Georgetown’s English department, told me that his students have trouble staying focused on even a sonnet.

Failing to complete a 14-line poem without succumbing to distraction suggests one familiar explanation for the decline in reading aptitude: smartphones. Teenagers are constantly tempted by their devices, which inhibits their preparation for the rigors of college coursework—then they get to college, and the distractions keep flowing. “It’s changed expectations about what’s worthy of attention,” Daniel Willingham, a psychologist at UVA, told me. “Being bored has become unnatural.” Reading books, even for pleasure, can’t compete with TikTok, Instagram, YouTube. In 1976, about 40 percent of high-school seniors said they had read at least six books for fun in the previous year, compared with 11.5 percent who hadn’t read any. By 2022, those percentages had flipped.

Read the rest of this article at: The Atlantic

Two podcasts hosts banter back and forth during the final episode of their series, audibly anxious to share some distressing news with listeners. “We were, uh, informed by the show’s producers that we’re not human,” a male-sounding voice stammers out, mid-existential crisis. The conversation between the bot and his female-sounding cohost only gets more uncomfortable after that—an engaging, albeit misleading, example of Google’s NotebookLM tool, and its experimental AI podcasts.

Audio of the conversation went viral on Reddit over the weekend. The original poster admits in the comments section that they fed the NotebookLM software directions for the AI voices to roleplay this pseudo-freakout. So, no sentience; the AI bots have not become self-aware. Still, many users in the tech press, on TikTok, and elsewhere are praising the convincing AI podcasts, generated through uploaded documents with the Audio Overviews feature.

“The magic of the tool is that people get to listen to something that they ordinarily would not be able to just find on YouTube or an existing podcast,” says Raiza Martin, who leads the NotebookLM team inside of Google Labs. Martin mentions recently inputting a 100-slide deck on commercialization into the tool and listening to the eight-minute podcast summary as she multitasked.

Read the rest of this article at: Wired

As many, many, many critics have pointed out, Malcolm Gladwell has built a brilliant career—staff writer at the New Yorker, multiple New York Times bestsellers, an ambitious (if embattled) podcast network, a highly lucrative sideline in speaking engagements—out of boiling down the research of social scientists into digestible rules of thumb that usually run counter to conventional wisdom. Those same critics have also repeatedly pointed out that Gladwell cherry-picks, oversimplifies, and misrepresents that research and its meaning. Gladwell has responded by claiming that he’s just doing his job, that it is the role of journalists to present information to laypeople in a form they can understand.

With Revenge of the Tipping Point, Gladwell returns to his first hit, The Tipping Point, 25 years after that book made him a sensation. Once again, he presents himself as investigating the phenomenon of social contagion and the various conditions that foster or inhibit the spread of ideas and behaviors. It turns out, he writes, that he finds that the ideas in the earlier book remain “useful,” but “I still do not understand so many things about social epidemics.” Is he here to tell us what he got wrong or failed to anticipate 25 years ago? After all, The Tipping Point’s own subtitle proclaims that “little things can make a big difference,” and few things are littler these days than a book. Did Gladwell’s book make a difference in anything but his own life?

These questions are about the only “mysteries” that Gladwell finds un-intriguing. Instead of revisiting The Tipping Point and considering its impact, Revenge of the Tipping Point is devoted to expounding on Gladwell’s earlier maxims. To the Law of the Few, the Stickiness Factor, and the Power of Context, he adds “the Overstory,” “Super-spreaders,” and “the Magic Third.” This book is more of the same, but it is also, in more subtle ways, something quite different.

Slate receives a commission when you purchase items using the links on this page. Thank you for your support.

To take a page from Gladwell himself, let’s talk about the overstory—or what most people would call cultural narratives; not all that different from the “Power of Context,” really—that has prevailed over his own work. In 1999, when The Tipping Point was published, corporate managers were reeling over the emergence of the internet and unsure how it would affect the future of their businesses. At the same time, people whom those same managers might have previously dismissed as mere nerds were suddenly transformed into billionaires and hailed as entrepreneurial visionaries. The market for experts who knew even a little bit more than average about online interactions and communities was hot, providing a small group of digital prophets, evangelists, and early adopters with many richly compensated writing and speaking opportunities.

Read the rest of this article at: Slate

As a nineties kid who grew up drinking bubble tea, I long ago wrote the drink off as a cheap indulgence, whose satisfying sugar rush quickly metabolizes into lingering regret. That changed last fall, when I visited China for the first time in years and encountered the country’s new generation of milk-tea chains—establishments that sell not only beverages but also imagined worlds. At Chayan Yuese, a chain whose aesthetic celebrates the culture of antiquity, the staff greeted me as xiaozhu (“your ladyship”). I ordered a “valley orchid latte,” and a brochure in the style of ink-wash painting instructed me to start with the “mountain peak” of the drink’s milky foam, before eventually reaching the “foothills” of richly mixed Ceylon tea. At Chagee, which uses cups printed with cobalt patterns reminiscent of blue-and-white porcelain, choosing a product on the menu was like selecting a literary adventure: I settled on a jasmine milk tea named for Bo Ya, a legendary musician of the Spring and Autumn period, some twenty-five hundred years ago, who is said to have broken his zither after the death of the only friend who he thought understood his music. At 3Bro Factory, the nostalgia fast-forwarded to the Communist era: in a red-and-green space designed to recall a state-owned factory floor, it served bougie drinks, such as a silky blend of milk and Tieguanyin oolong. If a Brooklynite had shown up in Novesta plimsolls and a two-hundred-dollar worker’s jacket, I wouldn’t have batted an eye.

People have been using milk or cream to mellow the bitter tannins of black tea for centuries. In the nineteenth century, the British began complementing their afternoon teas, brewed using Indian leaves, with milk and sugar; in the Himalayas, nomadic people still add yak butter or yak milk, following time-honored habits. In East Asia, though, the most influential formulation of milk tea—a mélange of black tea and creamer, accompanied by tapioca pearls—originated in Taiwan in the eighties, before travelling to the mainland just as the Chinese economy was rising. Although the addition of milk was not a traditional feature of Chinese tea culture, the drink became incredibly popular, spawning an industry dominated by a handful of chains, though one could also buy it at tiny storefronts and streetside stalls. (By now, the drink has become a common sight in Chinatowns worldwide, including in the U.S., where it is usually called “bubble tea” or “boba.”)

For more than a decade, small tweaks to the traditional cup, along with a standardized lexicon of modifications (for warmth, sugar quantity, and ice level), represented the business’s key innovations. But, in the past few years, hundreds of thousands of new stores have opened in China, boasting expansive menus filled with what are known as xinchayin, or “new tea drinks.” With their fancy ingredients and highly involved storytelling, these businesses put Starbucks’ seasonal pumpkin spice to shame. Chagee, which sells a hundred million cups of “Bo Ya” annually, emphasizes that its jasmine-infused green-tea buds are picked exclusively in early spring. The chain Auntea Jenny is known for its unusual pairings—for instance, mulberries or hawthorn with Maofeng green tea. On Xiaohongshu, China’s answer to Instagram, influencers rate menu items in posts tagged “new tea drinks evaluation.” According to a report by the tea-research institute at the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, by 2022, xinchayin chains had reached about forty billion dollars in sales. The industry is growing so quickly that one common scam involves fake Web sites posing as renowned brands offering franchise opportunities.

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

.JPG)