Dear readers,

We’re gradually migrating this curation feature to our Weekly Newsletter. If you enjoy these summaries, we think you’ll find our Substack equally worthwhile.

On Substack, we take a closer look at the themes from these curated articles, examine how language shapes reality and explore societal trends. Aside from the curated content, we continue to explore many of the topics we cover at TIG in an expanded format—from shopping and travel tips to music, fashion, and lifestyle.

If you’ve been following TIG, this is a chance to support our work, which we greatly appreciate.

Thank you,

the TIG Team

There’s a story about Sam Altman that has been repeated often enough to become Silicon Valley lore. In 2012, Paul Graham, a co-founder of the famed start-up accelerator Y Combinator and one of Altman’s biggest mentors, sat Altman down and asked if he wanted to take over the organization.

The decision was a peculiar one: Altman was only in his late 20s, and at least on paper, his qualifications were middling. He had dropped out of Stanford to found a company that ultimately hadn’t panned out. After seven years, he’d sold it for roughly the same amount that his investors had put in. The experience had left Altman feeling so professionally adrift that he’d retreated to an ashram. But Graham had always had intense convictions about Altman. “Within about three minutes of meeting him, I remember thinking, ‘Ah, so this is what Bill Gates must have been like when he was 19,’” Graham once wrote. Altman, too, excelled at making Graham and other powerful people in his orbit happy—a trait that one observer called Altman’s “greatest gift.” As Jessica Livingston, another YC co-founder, would tell The New Yorker in 2016, “There wasn’t a list of who should run YC and Sam at the top. It was just: Sam.” Altman would smile uncontrollably, in a way that Graham had never seen before. “Sam is extremely good at becoming powerful,” Graham said in that same article.

The elements of this story—Altman’s uncanny ability to ascend and persuade people to cede power to him—have shown up throughout his career. After co-chairing OpenAI with Elon Musk, Altman sparred with him for the title of CEO; Altman won. And in the span of just a few hours yesterday, the public learned that Mira Murati, OpenAI’s chief technology officer and the most important leader at the company besides Altman, is departing along with two other crucial executives: Bob McGrew, the chief research officer, and Barret Zoph, a vice president of research who was instrumental in launching ChatGPT and GPT-4o, the “omni” model that, during its reveal, sounded uncannily like Scarlett Johansson. To top it off, Reuters, The Wall Street Journal, and Bloomberg reported that OpenAI is planning to turn away from its nonprofit roots and become a for-profit enterprise that could be valued at $150 billion. Altman reportedly could receive 7 percent equity in the new arrangement—or the equivalent of $10.5 billion if the valuation pans out. (The Atlantic recently entered a corporate partnership with OpenAI.)

Read the rest of this article at: The Atlantic

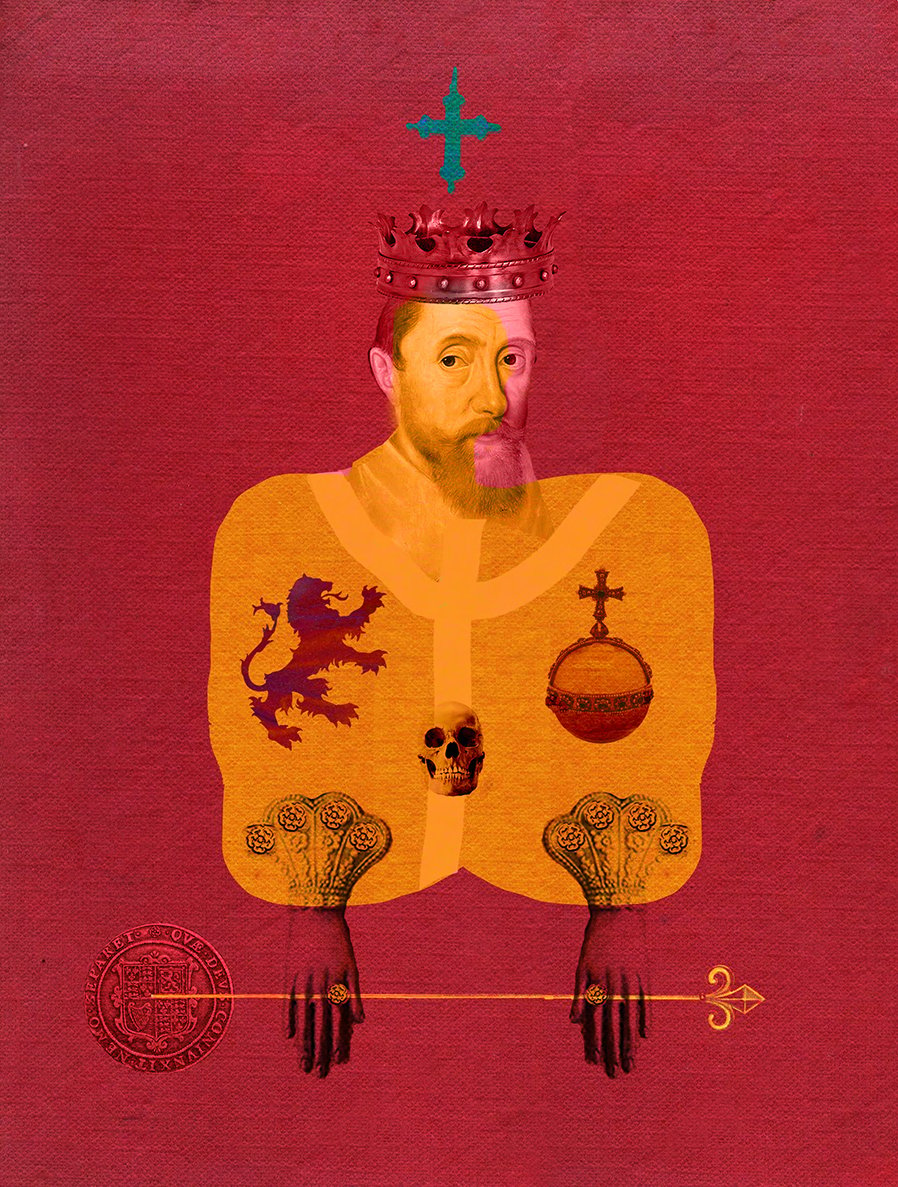

In 1609, James I lectured the English people on his rights and responsibilities as king. It was his duty to “make and unmake” them, he said. Kings have the “power of raising and casting down, of life and of death; judges over all their subjects, and in all causes.”

Not even the “general laws” of Parliament constrained him. The king stands “above” all human-made law. Indeed, it is his prerogative to “interpret” and to suspend such laws “upon causes only known to him.” He could also create new laws to whatever end he desired. The king, as James declared, is “accountable to none but God only.” He is the law speaking.

To enforce his personal rule of law, James could censor speech, the press, legal treatises, and the theater. He could imprison anyone, at any time, for any reason. And though the common law prohibited torture, James could use the rack, dungeon, and Skevington’s irons to get his way.

James also controlled a vast system of favoritism. Earldoms and knighthoods, positions in the state and church and universities, licenses to collect taxes or live in a particular house: all were his to grant. James could create offices as he saw fit. To win a vote in Parliament, James sometimes simply established new peerages. He minted licenses to do business and bestowed monopolies to manufacture or import cloth, tin, wine, even playing cards.

The quid pro quo was simple. In exchange for any such “patent” of “power or profit,” the beneficiary was to return funds and favors. After all, what the king could grant he could take away. In 1603, James imprisoned Sir Walter Raleigh and stripped him of most of his titles and properties. Some he gave to his own favorite, Robert Carr. Later, James gave many of Carr’s titles to a newer favorite, George Villiers, whom he named Duke of Buckingham.

Thus James sat on his throne, the center of a solar system in which every individual orbited around him, or as satellites of his satellites, a vast Cartesian mechanism propelled by venality and obsequiousness, reaching from the most magnificent of courtiers and intellectuals to the poorest of tenants in the remotest of shires.

Most historians do not believe that Louis XIV ever said, “L’État, c’est moi.” But even if apocryphal, this saying distills the idea of absolute monarchy in the days of James and France’s Sun King. Not that we need look four centuries back to understand how such absolutism works. Hitler, Stalin, Mao—each shaped the perception, thoughts, and truths of an entire people. So too Putin and Xi today.

For the first time since the founding, Americans find themselves debating much this same threat, of unfettered prerogative in the hands of a single man. It was Donald Trump’s success in teaching the Republican Party to scrape and grovel that first raised the specter of an authoritarian presidency. But it was the Supreme Court’s July 1 decision granting Trump immunity from criminal prosecution for most of his official actions as president that put flesh to the fear. As Justice Sonia Sotomayor summed up in her dissent: “In every use of official power, the President is now a king above the law.”

Read the rest of this article at: Aeon

Today’s generative AI systems like ChatGPT and Gemini are routinely described as heralding the imminent arrival of “superhuman” artificial intelligence. Far from a harmless bit of marketing spin, the headlines and quotes trumpeting our triumph or doom in an era of superhuman AI are the refrain of a fast-growing, dangerous and powerful ideology. Whether used to get us to embrace AI with unquestioning enthusiasm or to paint a picture of AI as a terrifying specter before which we must tremble, the underlying ideology of “superhuman” AI fosters the growing devaluation of human agency and autonomy and collapses the distinction between our conscious minds and the mechanical tools we’ve built to mirror them.

Today’s powerful AI systems lack even the most basic features of human minds; they do not share with humans what we call consciousness or sentience, the related capacity to feel things like pain, joy, fear and love. Nor do they have the slightest sense of their place and role in this world, much less the ability to experience it. They can answer the questions we choose to ask, paint us pretty pictures, generate deepfake videos and more. But an AI tool is dark inside.

Read the rest of this article at: Noema

If you step into the headquarters of the Internet Archive on a Friday after lunch, when it offers public tours, chances are you’ll be greeted by its founder and merriest cheerleader, Brewster Kahle.

You cannot miss the building; it looks like it was designed for some sort of Grecian-themed Las Vegas attraction and plopped down at random in San Francisco’s foggy, mellow Richmond district. Once you pass the entrance’s white Corinthian columns, Kahle will show you the vintage Prince of Persia arcade game and a gramophone that can play century-old phonograph cylinders on display in the foyer. He’ll lead you into the great room, filled with rows of wooden pews sloping toward a pulpit. Baroque ceiling moldings frame a grand stained glass dome. Before it was the Archive’s headquarters, the building housed a Christian Science church.

I made this pilgrimage on a breezy afternoon last May. Along with around a dozen other visitors, I followed Kahle, 63, clad in a rumpled orange button-down and round wire-rimmed glasses, as he showed us his life’s work. When the afternoon light hits the great hall’s dome, it gives everyone a halo. Especially Kahle, whose silver curls catch the sun and who preaches his gospel with an amiable evangelism, speaking with his hands and laughing easily. “I think people are feeling run over by technology these days,” Kahle says. “We need to rehumanize it.”

In the great room, where the tour ends, hundreds of colorful, handmade clay statues line the walls. They represent the Internet Archive’s employees, Kahle’s quirky way of immortalizing his circle. They are beautiful and weird, but they’re not the grand finale. Against the back wall, where one might find confessionals in a different kind of church, there’s a tower of humming black servers. These servers hold around 10 percent of the Internet Archive’s vast digital holdings, which includes 835 billion web pages, 44 million books and texts, and 15 million audio recordings, among other artifacts. Tiny lights on each server blink on and off each time someone opens an old webpage or checks out a book or otherwise uses the Archive’s services. The constant, arrhythmic flickers make for a hypnotic light show. Nobody looks more delighted about this display than Kahle.

It is no exaggeration to say that digital archiving as we know it would not exist without the Internet Archive—and that, as the world’s knowledge repositories increasingly go online, archiving as we know it would not be as functional. Its most famous project, the Wayback Machine, is a repository of web pages that functions as an unparalleled record of the internet. Zoomed out, the Internet Archive is one of the most important historical-preservation organizations in the world. The Wayback Machine has assumed a default position as a safety valve against digital oblivion. The rhapsodic regard the Internet Archive inspires is earned—without it, the world would lose its best public resource on internet history.

Its employees are some of its most devoted congregants. “It is the best of the old internet, and it’s the best of old San Francisco, and neither one of those things really exist in large measures anymore,” says the Internet Archive’s director of library services, Chris Freeland, another longtime staffer, who loves cycling and favors black nail polish. “It’s a window into the late-’90s web ethos and late-’90s San Francisco culture—the crunchy side, before it got all tech bro. It’s utopian, it’s idealistic.”

Read the rest of this article at: Wired

On the evening of September 6, 2008, David Foster Wallace convinced his wife Karen Green to go to the mall without him. Green was hesitant to leave her husband alone, as he had been struggling with his mental health for some time. Still, the fact that he had recently gone to the chiropractor seemed like a sign that things were under control. “You don’t go to the chiropractor if you’re going to commit suicide,” she told herself and went out the door.

Unfortunately, her assumption proved wrong. Once his wife was gone, Wallace wrote a two-page note and placed it next to the neatly arranged manuscript of his nearly complete novel The Pale King. He then walked out onto the patio of their home in Claremont, California, stood on a chair, and hanged himself. “This was not an ending anyone would have wanted for him,” author D.T. Max later wrote in his 2012 book Every Love Story is a Ghost Story, a Life of David Foster Wallace, “but it was the one he had chosen.”

Wallace grew up in Illinois, raised by a philosophy professor and English teacher who said “3.14159” instead of “pie” and made up words for things the dictionary had yet to give a name. He was a prolific student and avid tennis player, making up for lackluster athletic skills with an ability to calculate how the Midwestern winds would alter the trajectory of his strokes. These and other youth experiences he describes with dizzying detail in Derivative Sport in Tornado Alley, one of many he wrote for Harper’s Magazine, eventually compiled into a collection titled A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again. His fiction performed better still. “I am delighted to be in at the start of a brilliant career,” said the literary agent who took on his first novel, The Broom of the System, starting a partnership that would lead to the 1996 publication of Infinite Jest, Wallace’s best-selling magnum opus and one of Time magazine’s 100 best English-language novels published between 1923 and 2005.

Behind the scenes, however, Wallace’s accomplishments were overshadowed by his many mental health issues. As with so many other giants of world literature, the qualities that made him an astute and driven author — perfectionism, self-consciousness, and sensitivity — also hindered his ability to cope with the everyday challenges of being alive. Diagnosed with depression during his undergraduate years at Amherst College, he spent most of his adult life on Nardil, an antidepressant still available in the US today, but which has been discontinued in many other countries due to its many side effects.

In Wallace’s case, the prescription not only upset his stomach but also — or so he was convinced — diminished his creativity. Hoping to overcome writer’s block, he stopped taking Nardil in the summer of 2007. He entered this new phase of life with “a sense of optimism and a sense of terrible fear,” author Jonathan Franzen, who was friends with Wallace, told The New Yorker.

If Wallace had been a popular author before his death, news of his passing — and the tragic circumstances surrounding it — turned him into a veritable celebrity. Once read almost exclusively in the US, his following expanded across countries and continents. His former homes in Boston and Bloomington have become shrines for literary pilgrims, and his silhouette — his bandana and uncut rock-and-roll hair — is almost (almost) as recognizable as that of Che Guevara. Meanwhile, screen adaptations like The End of the Tour, starring Jason Segel and Jesse Eisenberg, have introduced him to a wider audience that may have been too daunted or disinterested to read his hefty books.

Read the rest of this article at: The Big Think