If you’ve been enjoying these curated article summaries that dive into cultural, creative, and technological currents, you may find the discussions and analyses on our Substack page worthwhile as well. There, I explore themes and ideas that often intersect with the subjects covered in the articles I come across during my curation process.

While this curation simply aims to surface compelling pieces, our Substack writings delve deeper into topics that have piqued our curiosity over time. From examining the manifestation of language shaping our reality to unpacking philosophical undercurrents in society, our Substack serves as an outlet to unpack our perspectives on the notable trends and undercurrents reflected in these curated readings.

So if any of the articles here have stoked your intellectual interests, I invite you to carry that engagement over to our Substack, where we discuss related matters in more depth. Consider it an extension of the curation – a space to further engage with the fascinating ideas these pieces have surfaced.

Slop started seeping into Neil Clarke’s life in late 2022. Something strange was happening at Clarkesworld, the magazine Clarke had founded in 2006 and built into a pillar of the world of speculative fiction. Submissions were increasing rapidly, but “there was something off about them,” he told me recently. He summarized a typical example: “Usually, it begins with the phrase ‘In the year 2250-something’ and then it goes on to say the Earth’s environment is in collapse and there are only three scientists who can save us. Then it describes them in great detail, each one with its own paragraph. And then — they’ve solved it! You know, it skips a major plot element, and the final scene is a celebration out of the ending of Star Wars.” Clarke said he had received “dozens of this story in various incarnations.”

These are prime examples of what is now known as slop: a term of art, akin to spam, for low-rent, scammy garbage generated by artificial intelligence and increasingly prevalent across the internet — and beyond. From their weird narrative instincts and inert prose, Clarke realized the stories came straight from ChatGPT. Sometimes they would arrive with the original prompt included, which was often as simple as “Write a 1,000-word science-fiction story.”

It was relatively easy to identify an AI-generated submission, but that required reading thousands (a “wall of noise”) and manually sorting them. Clarke compared the problem to turning off the spam filter and trying to read your email: “Okay, now multiply that by ten because that’s the ratio that we were getting.” Within weeks, the problem became unmanageable. “We had reached the point where we were on track to receive as many generated submissions as legitimate ones,” Clarke told me. Eventually, on February 20, he made the decision to close submissions temporarily. Clarkesworld had become one of the first victims of AI slop.

In the nearly two years since, a rising tide of slop has begun to swamp most of what we think of as the internet, overrunning the biggest platforms with cheap fakes and drivel, seeming to crowd out human creativity and intentionality with weird AI crap. On Facebook, enigmatic pages post disturbing images of maimed children and alien Jesuses; on Twitter, bots cluster by the thousands, chipperly and supportively tweeting incoherent banalities at one another; on Spotify, networks of eerily similar and wholly imaginary country and electronic artists glut playlists with bizarre and lifeless songs; on Kindle, shoddy books with stilted, error-ridden titles (The Spellbound Quest: Students Perilous Journey to Correct Their Mistake) are advertised on idle lock screens with blandly uncanny illustrations.

Read the rest of this article at: New York Magazine

The Other British Invasion: How UK Lingo Conquered The Us

I am an American, New York-born, but I started to spend time in London in the 1990s, teaching classes to international students. Being interested in language, and reading a lot of newspapers there – one of the courses I taught was on the British press – I naturally started picking up on the many previously unfamiliar (to me) British words and expressions, and differences between British and American terminology.

Then a strange thing happened. Back home in the United States, I noticed writers, journalists and ordinary people starting to use British terms I had encountered. I’ll give one example that sticks in my mind because it is tied to a specific news event, and hence easily dated.

In 2003, it became clear that the US would invade Iraq. Months passed; we did not invade. Then we did. Journalists faced a question: what should we call that preliminary period? In September 2003, the New York Times’ Thomas Friedman chose a Britishism, referring to “how France behaved in the run-up to the Iraq war”.

Run-up, previously unfamiliar in the US, quickly began to be very widely used. I know because of the app Google Books Ngram Viewer, the online tool that can measure the relative frequency with which a word or phrase appears in the vast corpus of books and periodicals digitised by Google Books (including separating out British and American use). Ngram Viewer shows that between 2000 and 2005, American use of “the run-up to” increased by 50%.

This phrase was not – to use a Britishism that’s dear to my heart – a one-off. Over the next several years, I started noticing dozens and dozens of other examples. Finally, in 2011, I decided to chronicle this phenomenon in a blog called Not One-Off Britishisms.

In 1781, US founding father John Witherspoon coined the term “Americanism” and started complaining about the way words concocted by the ex-colonists were polluting the purity of the English language. Far from diminishing over the years, the resentment bordering on outrage has continued apace. Just weeks ago, in the Telegraph, Simon Heffer whinged that – as the headline of his piece put it – “Americanisms are poisoning our language”.

So it can come as a shock to Britons to learn that their words and expressions have been worming their way into the American lexicon just as much, it would appear, as the other way around. I date the run-up (that’s an alternate meaning of run-up: “increase”) in Britishisms to the early 1990s, and it’s surely significant that this was when such journalists as Tina Brown, Anna Wintour, Andrew Sullivan and Christopher Hitchens moved to the US or consolidated their prominence there. The chattering classes – another useful Britishism – have a persistent desire for ostensibly clever ways to say stuff. They have borrowed from Wall Street, Silicon Valley, teen culture, African American vernacular, sports and hip-hop, and they increasingly borrow from Britain.

Here are some of my favourite examples.

Read the rest of this article at: The Guardian

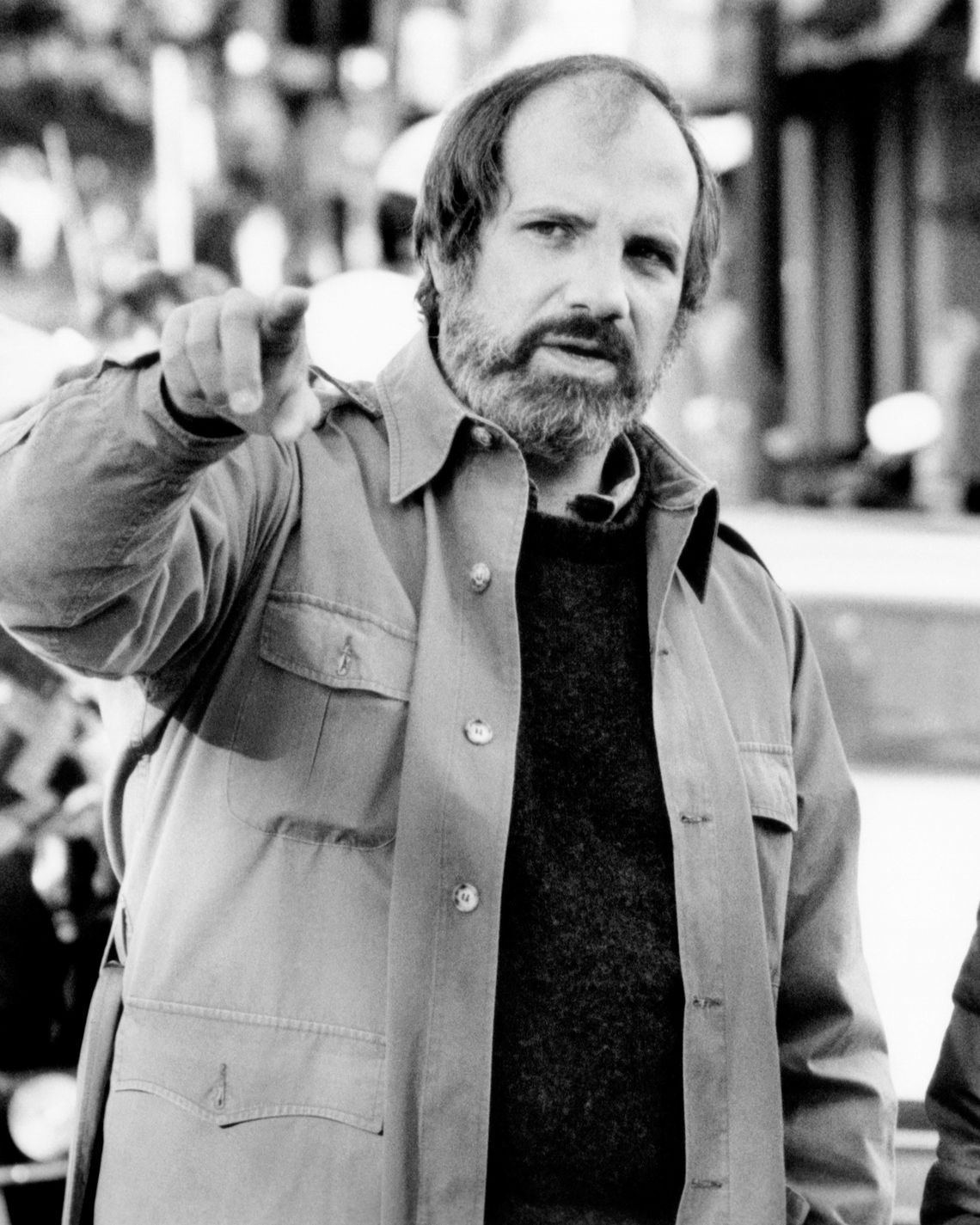

Brian De Palma’s 1984 thriller Body Double was seen by many at the time as a deliberate provocation — a vigorously thumbed nose at the commentators who’d called his work misogynistic and sadistic as well as at the MPAA, which had given his 1983 film Scarface an X. De Palma himself reportedly said that Body Double was meant to go over the top in all of his alleged cinematic sins. The 84-year-old director now admits that was mostly publicity-friendly bluster. But the movie, which is coming out in a special 4K edition to honor its 40th anniversary, is extreme in all sorts of ways: It’s gory, violent, sexy, stylized, ridiculous, an extremely suspenseful picture that is somehow impossible to take too seriously. It also happens to be a masterpiece, which would come as a surprise to the critics and audiences that rejected it back during its release: The film flopped at the box office, De Palma was nominated for a Worst Director Razzie, and even Pauline Kael, a longtime defender of his, called it “an awful disappointment.” Looking back on it now, De Palma says, “You’re always judged by the style of the day, but sometimes the style of the day is not the right way to appraise something innovative.”

Read the rest of this article at: Vulture

The Substance, director Coralie Fargeat’s new body-horror film about the curse of aging in Hollywood, is masterfully well-crafted. Every frame, taken individually, could be installed in a gallery like a work of art. Every editing and sound choice is calculated to extract maximum audience discomfort. Ordinary noises are blasted into our eardrums at high volumes, like reverse ASMR, and there’s never a stationary camera shot when something swooping or low-angled or maximum close-up could exist in its stead. Demi Moore and Margaret Qualley, as two halves of a self divided by the titular Substance, commit to frank unsexual nudity and many varieties of physically and emotionally extreme performance in ways that display both actors working at the top of their game. I’m still dazzled on the level of pure spectacle. Still, there’s something off in its central conceit.

Yes, the movie is clearly using maximalism and shock value to make its points. But the price of being thrilled by The Substance is accepting wholesale that a woman would be willing to give up her life seven days at a time to permit a version of her young, beautiful self to parade around in the world in her stead. The two selves don’t share a mind, so the old self must just sit around and watch TV while the new self paints the town. Why, I wondered, would anyone make that bargain? My inability to suspend my disbelief may be in part because Demi Moore, who plays faded star Elisabeth Sparkle, is one of the most beautiful 62-year-olds on the planet. If you’re already fairly perfect, why sacrifice everything to allow a glistening Margaret Qualley to burst forth from your spinal column?

When we first meet Elisabeth, it’s via symbolism: We see a montage of her Walk of Fame star being scrupulously installed, shiny at first then, over the years, fading and cracking and ignored by the tourists who walk over it, noticing it less and less. We then meet real-life Elisabeth on the set of her long-running aerobics show, sweating it out in a skintight leotard and tights, looking fantastic. But not fantastic enough for Dennis Quaid’s Harvey, the head of the studio and avatar of everything masculine and rapacious in Hollywood. In shiny suits and clanking boots, his face distorted in punishing close-up, he loudly masticates shrimp at lunch in a way that will make you never want to eat shrimp again. As he does so, he fires Elisabeth from her show for being too old. She promptly goes out and crashes her shiny red car because she’s distracted from the road by the sight of her outsize face being peeled off a billboard. At the hospital afterward, she’s pronounced unscathed, but a gleamingly youthful medical assistant slips her a card with a phone number and the words “The Substance” wrapped inside a note that says “It changed my life.”

Read the rest of this article at: The Cut

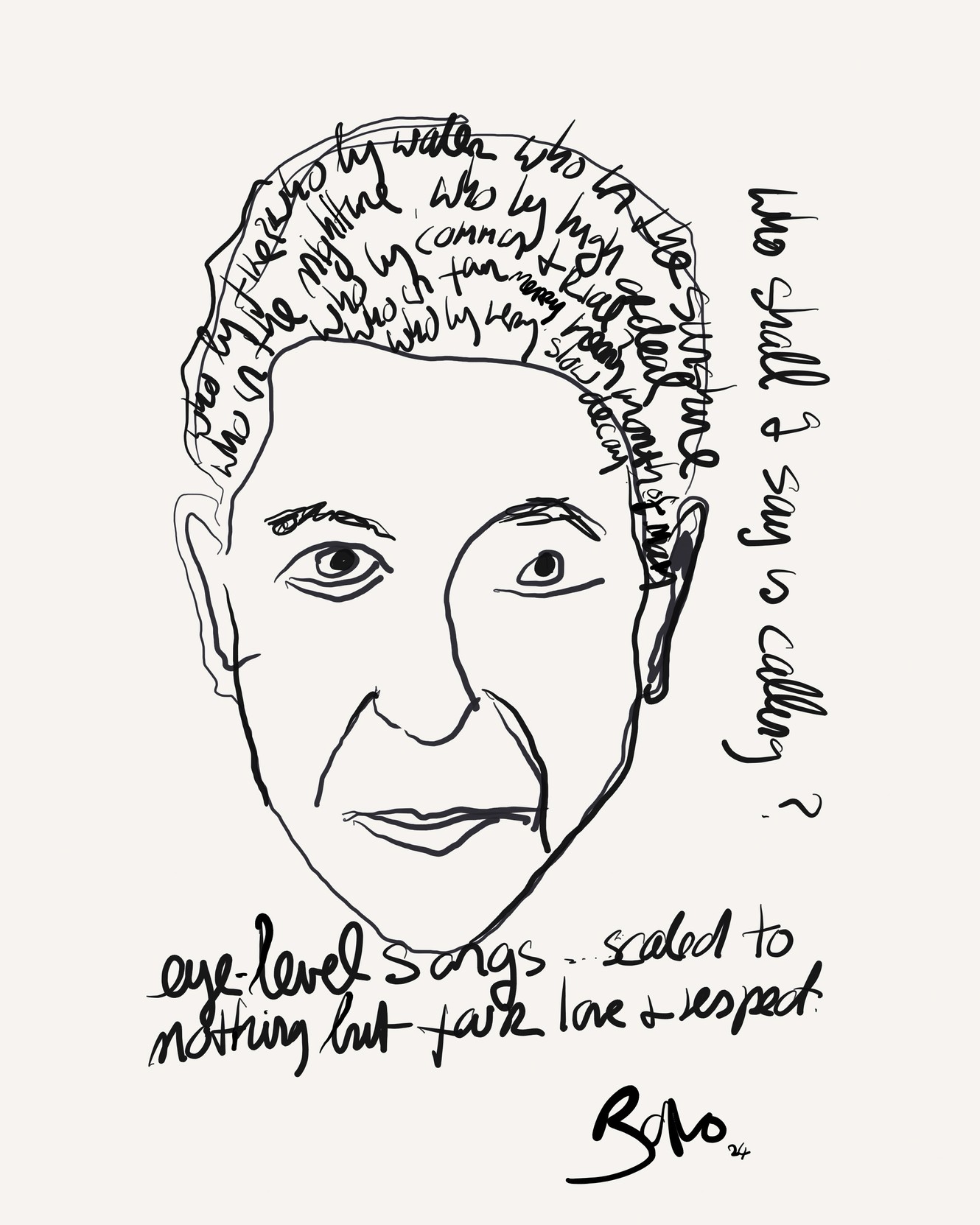

The Anti–Rock Star

Leonard Cohen never liked touring. “It’s like being dropped off in a desert,” he once said. “You don’t know where you live anymore.” By the time he hit his late 50s, he hated it so much that, after supporting his 1992 record, The Future, he moved into a Zen monastery and all but retired from the music business. Even after he returned with More Best of Leonard Cohen (1997), a wonderful celebration of his mid-career prime, he refused to cash in with a fresh calendar of live shows. Then, in 2005, he discovered that his bank account had been nearly emptied by his business manager.

Cohen spent months in rehearsal with a band, fine-tuning his songs as he now wanted to play them—more quietly, more elegantly than ever. In 2008, at 73, he went back out on the road. Other than at a book signing, he hadn’t performed live in more than a decade. But something had happened in the interim.

His audience was larger—lines curving around blocks, scalpers demanding hundreds above face value. More striking, though, was the depth of feeling. Leonard Cohen, master of a cool, ironic, deadpan remove, had come to signify something new that mystified the performers themselves. “I saw people in front of the stage shaking and crying,” a backup singer noted after opening night. “You don’t often see adults cry, and with such violence.”

The highlight of the tour came at the Glastonbury Festival, where Cohen played the main stage in front of listeners young and old. As the sun set and Cohen sang “Hallelujah,” concertgoers “sang along, clutching each other’s arms,” an Australian journalist reported, “and many were openly weeping.” Cohen hadn’t been dropped off in a desert.

How to account for such emotion, felt across generational divides? Where does the widely perceived authenticity—hardly an untroubled term—of this music come from? And why has its power to move listeners sustained itself so forcefully, turning Cohen’s afterlife into one long canonization?

Read the rest of this article at: The Atlantic