If you’ve been enjoying these curated article summaries that dive into cultural, creative, and technological currents, you may find the discussions and analyses on our Substack page worthwhile as well. There, I explore themes and ideas that often intersect with the subjects covered in the articles I come across during my curation process.

While this curation simply aims to surface compelling pieces, our Substack writings delve deeper into topics that have piqued our curiosity over time. From examining the manifestation of language shaping our reality to unpacking philosophical undercurrents in society, our Substack serves as an outlet to unpack our perspectives on the notable trends and undercurrents reflected in these curated readings.

So if any of the articles here have stoked your intellectual interests, I invite you to carry that engagement over to our Substack, where we discuss related matters in more depth. Consider it an extension of the curation – a space to further engage with the fascinating ideas these pieces have surfaced.

Back in July, the journalist Ezra Klein interviewed Elaina Plott Calabro, a staff writer at The Atlantic, on his popular podcast, “The Ezra Klein Show.” Calabro had profiled Kamala Harris the previous year, and Klein wondered whether the Vice-President was “underrated” as a potential challenger to Donald Trump. Harris, Klein said, reminded him of Hillary Clinton, insofar as both politicians “struggled with this question of authenticity, struggled to seem like they were themselves, giving a big speech.” In small settings, he went on, Harris was “extremely warm and magnetic and profane, much more so than a lot of politicians who I know. . . . You’d want to go to the barbecue or the party she hosted.” There was no politician, Klein ventured, for whom “a bigger gap” existed between “charisma on the stump” and “charisma around a table.” Calabro concurred: “Once she gets in a smaller group and she’s able to really level with the person that she’s speaking to and has eyes on them, she, I think, becomes a completely different person.”

Two months later, we all know this completely different person. Harris, suddenly, now comes across as a naturally gifted big-stage politician. In front of even the largest audiences, she radiates intelligence, warmth, and an exuberant swagger characterized by observers, and by Harris herself, as “joy.” Good vibes are at the center of her campaign: one of the core promises of the Harris-Walz ticket is that the people in charge will be normal, human, and positive, rather than freakish, rageful, and “weird.” Originally seen mainly as a generic alternative to Trump (“I’d vote for a cabbage,” a relative told me, this summer), Harris now seems compelling in her own right. What happened? Did she somehow transform? Or did countless observers drastically misjudge a politician who’d been in the public eye for years?

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

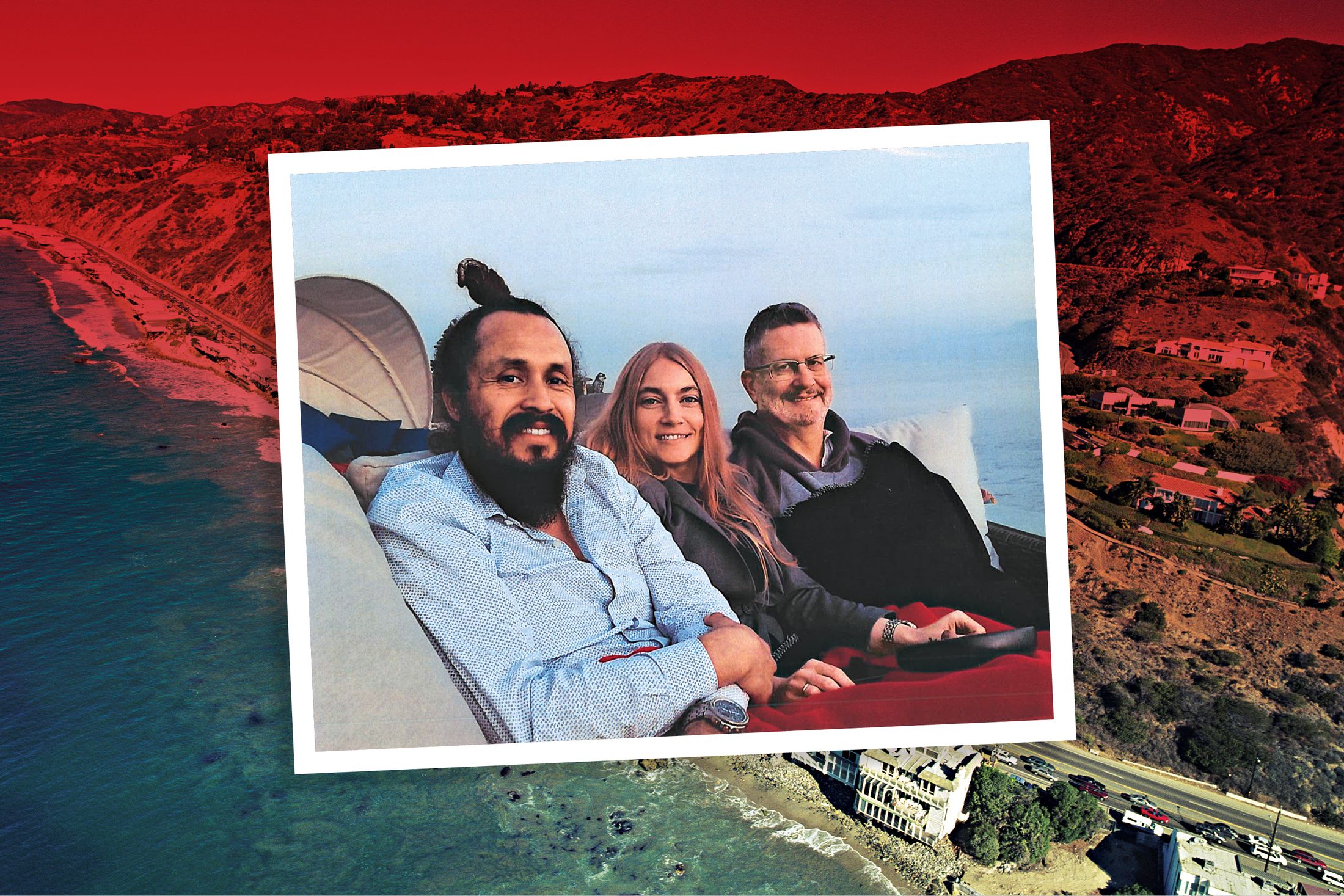

On a Friday afternoon in June 2017, Anthony Flores and his girlfriend, Anna Moore, decided to go out for vegan ice cream at Kippy’s. Though the pair lived 220 miles away, in Fresno, California, they were regulars at the Venice Beach ice-cream shop. “They came in all the time. They were striking,” says the owner, Kippy Miller. The couple did have a distinct look. Even for a casual trip, they tended to wear matching suits and ties. “I just don’t ever remember seeing them with another person,” Miller adds. As the couple looked at the flavors, a middle-aged man with closely cropped gray hair approached. Dr. Mark Sawusch, an ophthalmologist, had a question for the duo: “Do you know anything about this alkaline water?” They did, as it turned out.

As far as anyone seems to know, the meeting at Kippy’s happened entirely by chance. Sawusch’s office was nearby, but otherwise he and the couple traveled in different circles. He examined eyes; they owned a yoga studio. In any case, by that evening, they had the keys to the doctor’s silver Tesla. A week later, Flores texted Sawusch to offer his and Moore’s help: “Our desire is to add ease and flow to your life and be of great service.” Sawusch responded, calling the couple “the BEST friends I have ever met in my entire life.” They moved from their apartment into his Malibu beach house that same day. In a few months, the doctor would be dead. For the next six years, people would wonder: Were Flores and Moore scammers who stumbled upon the perfect mark in a vegan-ice-cream shop? Or were they simply trying to help a man coming off the worst year of his life?

The version of the couple Sawusch met that day was just their latest iteration; they had both reinvented themselves several times over. Flores was raised in a lower-middle-class Mexican American family in Clovis, a conservative agricultural city outside Fresno in the humid Central Valley. In 1994, he graduated from Clovis High School, where he was voted both prom king and “Most Artistic.” Instead of going to college, he started a window-washing business, targeting clients in wealthy neighborhoods and winning them over with his warm and engaging demeanor. People simply liked him. “Word just got out,” says his childhood best friend, Dave Brose. “He was actually making a lot of money.” In 2005, a strange situation put him in the public eye: He learned that he’d been unnecessarily paying his ex-girlfriend Amber Frey child support — $175 of his hard-earned window-washing money every month for four years. Frey had just been outed as Scott Peterson’s mistress, which meant the alimony situation landed Flores all over the news, looking foolish. “He got swindled big time. That hurt him. It really, really did,” Brose says.

Read the rest of this article at: The Cut

“In the Cut,” which premièred in 2003, is Jane Campion’s most ghettoized picture. The New Zealand director has been lauded for films such as “The Piano,” about motherhood and marriage, and “The Power of the Dog,” her subversive Western. But when she takes her interesting periodic leaves from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, some critics, it seems, are not down. (Some are, such as Manohla Dargis, who described “In the Cut” as an “astonishingly beautiful new film” that might be “the most maddening and imperfect great movie of the year,” but most reviewers expressed pure bafflement, bordering on derision.) The film is about Frannie Avery, an English professor (Meg Ryan) whose erotic revitalization is ignited by her attraction to a cop, Detective Malloy (Mark Ruffalo), who is investigating killings in lower Manhattan. These murders are femicides—the killer targets, kills, and then dismembers women, leaving behind an engagement ring as his signature.

To be a woman in the universe of “In the Cut” is to be hunted. Marriage is no refuge. Objections to the movie ranged from aesthetic to moral. Its soft-focus visual world—the sequences of sunbursts obliterating any view of downtown and its people, with those people enveloped in grease and heat—was too pretentious. There was also the upset about Ryan, who shows her breasts—a sweetheart made impure through pulp fiction. The prevailing narrative was that Campion had done the erotic thriller wrong, that her exploration of the hunted woman reeked of a shallow “post-feminist” caprice.

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

It was past curfew. My friend cut his headlights and dropped me off in my driveway. From the little peaked window atop the garage, yellow light filtered. Someone was in the attic.

I walked up the pebble path that bordered the house, opened the side door, and stepped into the garage. It was hot. It was dark. The ladder to the attic was folded down, and from the ceiling-access square a faint light glowed. I heard my mother’s voice. I took a step closer to catch what she was saying.

“Mom?” I said.

I heard a click. She stopped talking.

“Beth Anne?” my dad said from above.

“Dad? What are you doing?”

“I’ll be in in a little bit.”

I walked into the house and down the hallway and peeked into my parents’ room. My mother was asleep on her side of the bed.

A few years later, when I was away at college, I learned that my father had been tapping the phone lines. My mother had been adamant: “I am not cheating. I am not a cheater. When do I have time to cheat?” But my father’s career in car sales had given him a sensitive radar for dishonesty. So starting when I was in high school, in the mid-1990s, he would climb into the attic after she went to bed and situate himself at a makeshift station he had equipped with wires, jacks, and recording devices.

Dad’s goal was to gather evidence to use as leverage in the divorce. He also used the recordings to exact revenge. After he found out that Mom bought a slinky yellow dress — a dress he thought she certainly wasn’t planning to wear for him — he cut off her credit cards. On another day, Dad traded in her car. Just before they entered divorce proceedings, in 1997, I remember my father making copies of the tapes, packaging them neatly in brown paper (this is a man I never saw wrap a Christmas present), and sending them to some of our relatives in Ohio. He wanted to show that he had proof: of my mother’s secretive behavior as well as the emotional and psychological harm he felt she had inflicted upon him. My father had a name for this body of evidence. He called them the Divorce Tapes.

One of my cousins threw his copy of the tapes into a fire — they were upsetting to his mother, and he wanted them gone. An aunt who was recorded saying “How did he do that? He’s not smart enough to tap” says she never received them. Another aunt, my father told me, sent the tapes back with a yellow Post-it attached: TOO MUCH CUSSING!

Read the rest of this article at: The Cut

As my boat cruises toward the private island city of Indian Creek Village — better known as the Billionaire Bunker — I’m hoping my trip doesn’t end in an arrest.

It’s a hot morning on South Florida’s Biscayne Bay, and I’ve convinced two local tour boat captains to pilot me around the perimeter of what is quite possibly the wealthiest and most heavily defended town in America. I’m not entirely clear on the rules about boating near the island, which lies just across the bay from Miami, and neither are my captains — they’re both in their first weeks on the job. What I do know is that Indian Creek employs a new all-seeing security system and a small navy of police officers who frequently stop and ticket boats that venture too close to the island’s manicured shore.

As we near the northwestern side of the island, I spot the bright red steel beams of “La Petite Clef,” the Mark di Suvero sculpture that towers 20 feet over the front lawn of the car magnate Norman Braman’s mansion. We glide past a modern palace hidden behind a dense cluster of palm trees, purchased for $50 million in 2019 by a mysterious LLC linked to the emir of Qatar. On the southwestern shore, we come upon the island’s most sought-after mansions. This is where the elite of the elite live: Tom Brady, Carl Icahn, and the neighborhood’s most recent arrival, Jeff Bezos. The wealth here is staggering — 25,000-square-foot mansions with ivy-strewn stucco walls, fronted by sprawling lawns and sleek yachts. Today, almost all the mansions appear to be empty.

As we get closer to the shore, I start to notice the cameras.

Their beady eyes are everywhere. Some are mounted on poles along the seawall. Others peek out from hedges. Many are connected to an inconspicuous white box — an Israeli-designed radar system capable of detecting passersby, in low visibility, from half a mile away.

There is no way for a person to set foot on Indian Creek without the express permission of one of its 89 residents or a member of its ultra exclusive country club, which reportedly costs $500,000 to join. Because the town’s government serves such an ultra wealthy subset of the population, things like public parks and social programs are practically nonexistent. Instead, the lion’s share of Indian Creek’s budget goes to its police department — which keeps watch on the island’s sole entrance and patrols the perimeter 24/7. Through federal funds, the town has also amassed a panoply of other security measures that would make Bezos’ Ring cameras blush.

“The wealthier you become, the more you want perfect security,” says Setha Low, the director of the Public Space Research Group, a center at the City University of New York that focuses on the access and control of everything from city parks to gated communities. “And that produces an industry making a lot of money off of people’s fear.” Much like the military-industrial complex, she says, “there’s a security-industrial complex — this entire sector of our economy being fed by people wanting this kind of security.”

Read the rest of this article at: Business Insider