If you’ve been enjoying these curated article summaries that dive into cultural, creative, and technological currents, you may find the discussions and analyses on our Substack page worthwhile as well. There, I explore themes and ideas that often intersect with the subjects covered in the articles I come across during my curation process.

While this curation simply aims to surface compelling pieces, our Substack writings delve deeper into topics that have piqued our curiosity over time. From examining the manifestation of language shaping our reality to unpacking philosophical undercurrents in society, our Substack serves as an outlet to unpack our perspectives on the notable trends and undercurrents reflected in these curated readings.

So if any of the articles here have stoked your intellectual interests, I invite you to carry that engagement over to our Substack, where we discuss related matters in more depth. Consider it an extension of the curation – a space to further engage with the fascinating ideas these pieces have surfaced.

The only thing that has kept me alive is that I’m a petty bitch,” says Stormy Daniels. “There would be too many people happy if I died. I’m alive because of spite.”

Daniels is sitting on the back porch of an undisclosed domicile, in an undisclosed city in an undisclosed state. There’s a gun on the table beside her, which, she says, she carries wherever she goes — “but never in a state where it’s illegal,” she quickly adds. “Let’s not give them a reason to search me.”

For the past few months, she and her husband, adult-film star and director Barrett Blade, have been traveling across the country in an RV, with Daniels doing stand-up and promoting voter-registration efforts. They fled their home in the middle of the night after the New York Post published a photo of her house — the result, she believes, of her testimony at former President Donald Trump’s criminal trial in May, when Trump’s defense team displayed an unredacted document containing her address in the courtroom. She says she was doxed immediately, with Trump supporters barraging her with death threats, forcing her to flee and relocate her beloved horses. (Daniels is a competitive equestrian.)

Daniels has her own theory as to why she was doxed, but ultimately, her explanation is simple: “They’re just trying to break me in every way possible,” she says flatly.

Throughout our conversation, Daniels frequently refers to an amorphous “they.” Sometimes, she is explicit about who “they” is in reference to: Either it’s Bill Maher, who accused her of being a “bad witness” in Trump’s trial (“I’m gonna punch him in his little tiny dick”); or Megyn Kelly, who speculated that Daniels’ encounter with Trump was a “setup” (“What a hypocritical twat”); or Michael Avenatti, her former attorney who is currently serving time in prison for embezzling $300,000 from her (“What a little bitch”); or Susan Necheles, Trump’s defense attorney, who subjected her to intense cross-examination (“She looks like someone put Richard Simmons in the microwave, OK? No — she looks worse than Richard Simmons does now”).

Read the rest of this article at: Rolling Stone

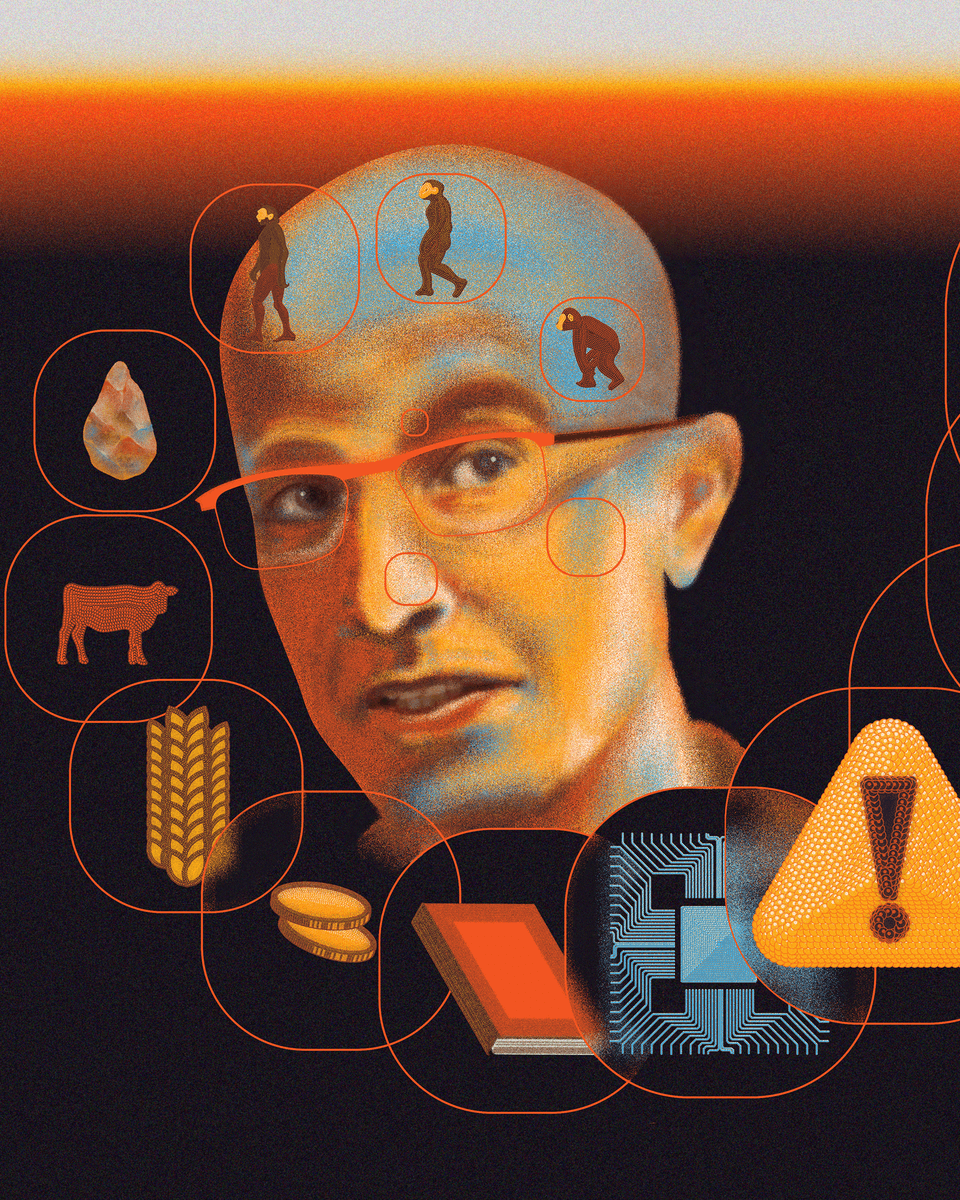

“About 14 billion years ago, matter, energy, time and space came into being.” So begins Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind (2011), by the Israeli historian Yuval Noah Harari, and so began one of the 21st century’s most astonishing academic careers. Sapiens has sold more than 25 million copies in various languages. Since then, Harari has published several other books, which have also sold millions. He now employs some 15 people to organize his affairs and promote his ideas.

He needs them. Harari might be, after the Dalai Lama, the figure of global renown who is least online. He doesn’t use a smartphone (“I’m trying to conserve my time and attention”). He meditates for two hours daily. And he spends a month or more each year on retreat, forgoing what one can only presume are staggering speaking fees to sit in silence. Completing the picture, Harari is bald, bespectacled, and largely vegan. The word guru is sometimes heard.

Harari’s monastic aura gives him a powerful allure in Silicon Valley, where he is revered. Bill Gates blurbed Sapiens. Mark Zuckerberg promoted it. In 2020, Jeff Bezos testified remotely to Congress in front of a nearly bare set of bookshelves—a disquieting look for the founder of Amazon, the planet’s largest bookseller. Sharp-eyed viewers made out, among the six lonely titles huddling for warmth on the lower-left shelf, two of Harari’s books. Harari is to the tech CEO what David Foster Wallace once was to the Williamsburg hipster.

This is a surprising role for someone who started as almost a parody of professorial obscurity. Harari’s first monograph, based on his Oxford doctoral thesis, analyzed the genre characteristics of early modern soldiers’ memoirs. His second considered small-force military operations in medieval Europe—but only the nonaquatic ones. Academia, he felt, was pushing him toward “narrower and narrower questions.”

What changed Harari’s trajectory was taking up Vipassana meditation and agreeing to teach an introductory world-history course, a hot-potato assignment usually given to junior professors. (I was handed the same task when I joined my department.) The epic scale suited him. His lectures at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, which formed the basis for Sapiens, told the fascinating tale of how Homo sapiens bested their rivals and swarmed the planet.

Harari is a deft synthesizer with broad curiosity. Does physical prowess correspond to social status? Why do we find lawns so pleasing? Most scholars are too specialized to even pose such questions. Harari dives right in. He shares with Jared Diamond, Steven Pinker, and Slavoj Žižek a zeal for theorizing widely, though he surpasses them in his taste for provocative simplifications. In medieval Europe, he explains, “Knowledge = Scriptures x Logic,” whereas after the scientific revolution, “Knowledge = Empirical Data x Mathematics.”

Heady stuff. Of course, there is nothing inherently more edifying about zooming out than zooming in. We learn from brief histories of time and five-volume biographies of Lyndon B. Johnson alike. But Silicon Valley’s recent inventions invite galaxy-brain cogitation of the sort Harari is known for. The larger you feel the disruptions around you to be, the further back you reach for fitting analogies. Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey famously compared space exploration to apes’ discovery of tools.

Read the rest of this article at: The Atlantic

The first time it happened, it was an accident. But every dream is.

It would have been my last REM cycle of the night, had I been able to sleep. Instead, for the previous six hours, I had counted sheep, had dressed for imaginary occasions in my mind, had tried the Army sleep techniques, alternately imagined myself in a black velvet hammock and in a canoe on a calm, still lake. I’d meditated. I’d thought of my mother, a lifelong insomniac who has rarely slept more than four hours a night in her life. I’d tried everything and given up. All I could do was wait for morning.

The dream grabbed my ankles first, pulled at me like someone dislodging a drain. Out it tossed me through my sliding glass window, over the garden, over my quiet street, over the dark sleeping skyline, a ragdoll flung into the Santa Anas. I soared high enough to see Los Angeles’s motherboard of electric light. I could see the city in perfect detail below. I was asleep — no, I was awake! I felt the cold whipping through my hair as I tumbled like a deflating balloon through the sky. I felt the miles beneath me. I felt the warm pillow beneath my cheek. I dove, flew, dipped, conscious of it all.

So this is a lucid dream, I thought.

Read the rest of this article at: Noema

‘As they say that Helen of Argos had that universal beauty that every body felt related to her, so Plato seems to a reader in New England an American genius. His broad humanity transcends all sectional lines.’

– from ‘Plato; or, the Philosopher’; Representative Men (1850) by Ralph Waldo Emerson

‘Only Hegel is fit for America – is large enough and free enough.’

– from an unpublished lecture on German philosophy; Notebooks by Walt Whitman (1819-92)

What is the future of philosophy in the United States? This question weighs heavily on teachers and scholars as philosophy departments around the country – at schools rich and poor, large and small – blink out of existence. Some are eliminated as part of an institution-wide downsizing effort, as operating budgets and endowments contract; others are simply pillaged for resources to give to other programs that more readily display the one virtue recognised by administrators: ‘impact’.

However, compared with other disciplines in the humanities experiencing rapid decline in majors and enrolments – English, history, languages and so forth – philosophy hangs on as a common minor or second, subordinate major for students pursuing degrees in law, politics or the natural sciences. Nevertheless, philosophy departments routinely wind up on the chopping block when administrators and educational consultants write up their plans for institutional restructuring, even if their elimination brings no obvious benefit.

Consider Manhattan College, for instance, a Catholic institution in New York that announced the elimination of their philosophy major earlier this year. In an interview with the campus newspaper, an anonymous faculty member said:

Philosophy is one of the strongest, fastest-growing programs at Manhattan College … we have over 20 per cent more students taking philosophy classes this year than last year … Closing the philosophy major and minor does not save any money.

This is just one example of many, all of which tell that the circumstances for studying philosophy in a college or university setting, democratised by the post-Second World War expansion of higher education, are in the midst of great change, if not dying out altogether.

The history of philosophical study in the US offers some insight into what this great change might look like. In the mid-19th-century US Midwest, two schools of philosophy appeared whose rivalry and work would shape a century of how philosophy was learned and studied, and not just in the US.

Read the rest of this article at: Aeon

In 1977, the artist, musician, and producer Brian Eno was in Berlin, working with David Bowie on the album that would become “Heroes.” They’d been collaborating on a song in an unconventional way, using a deck of cards called “Oblique Strategies,” which Eno had developed together with the artist Peter Schmidt. There were more than a hundred cards in the deck, and printed on each was a creative prompt, such as “What to increase? What to reduce?,” “A line has two sides,” or “Honour thy error as a hidden intention.” Eno and Bowie had each taken a card, then slipped it into a pocket. Neither knew what the other had drawn. They were taking turns working on the song, following different hidden ideas.

In “Eno,” the new documentary by Gary Hustwit, Eno chuckles, recalling that the song took a long time to complete, in large part because his card suggested that he “change nothing and continue with immaculate consistency,” while Bowie’s advised him to “destroy the most important thing.” The song itself, “Moss Garden,” doesn’t suggest two artists working at cross-purposes; it’s a contemplative riff on Japanese music, meant to evoke a peaceful place that Bowie had visited in Kyoto. And yet it’s restless in a way that makes it endlessly listenable, with strange, rocket-like sounds in the far distance and mutating birdsong swirling around Eno’s synthesizer and Bowie’s koto.

I’ve listened to music recorded or produced by Eno nearly every day for decades. He’s well known for coining the term “ambient music” (his “Discreet Music,” from 1975, is a landmark in the genre) and for working on career-defining records by Bowie, Talking Heads, U2, and others; for the past few decades, he’s also made “generative” music, in which computer programs work within parameters he’s set to create compositions that unfold infinitely. More broadly, though, he’s developed a recognizable approach to creativity that’s cerebral, chance-driven, hands-off, impersonal, collaborative, meditative, ecological, extended in time, and open to accident. In the high-pressure environment of a recording studio, where every hour costs money, he introduces layers of abstraction, randomness, and play.

There’s a sense in which music is the most immediate of art forms: it’s pure physicality, as our bodies make art by vibrating the air. And yet it can also be strange, fleeting, and distant. In his poem “To Music,” Rainer Maria Rilke wrote:

You are the transformation

of all feeling into—what? . . . audible landscape.

. . . the other side of the air,

pure,

immense,

no longer lived in.

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker