If you’ve been enjoying these curated article summaries that dive into cultural, creative, and technological currents, you may find the discussions and analyses on our Substack page worthwhile as well. There, I explore themes and ideas that often intersect with the subjects covered in the articles I come across during my curation process.

While this curation simply aims to surface compelling pieces, our Substack writings delve deeper into topics that have piqued our curiosity over time. From examining the manifestation of language shaping our reality to unpacking philosophical undercurrents in society, our Substack serves as an outlet to unpack our perspectives on the notable trends and undercurrents reflected in these curated readings.

So if any of the articles here have stoked your intellectual interests, I invite you to carry that engagement over to our Substack, where we discuss related matters in more depth. Consider it an extension of the curation – a space to further engage with the fascinating ideas these pieces have surfaced.

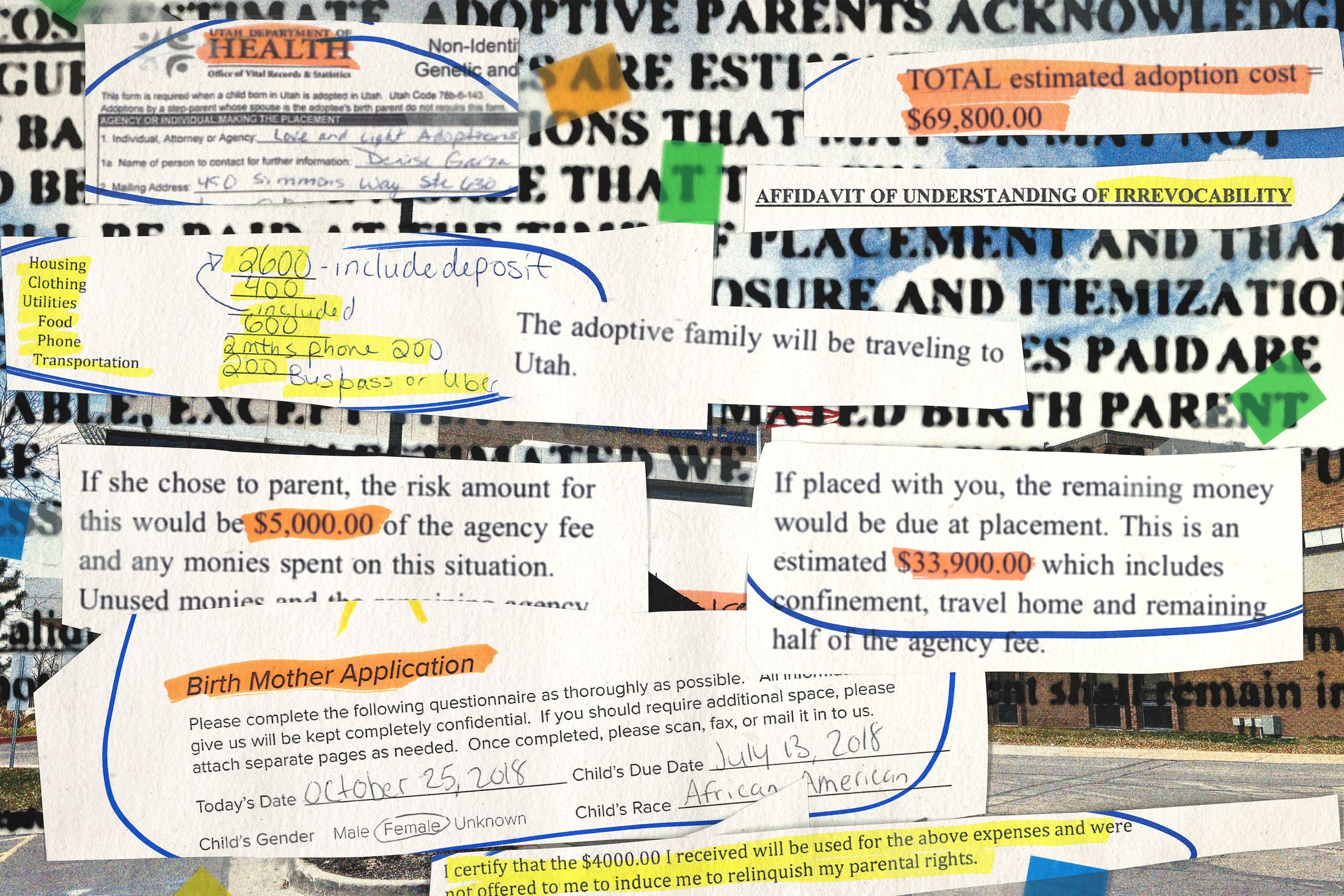

When Tia Goins gave birth to her daughter, Tiona, in July 2018, she vowed that she would provide her a different life than the one she’d had. Goins had been abandoned at birth by a mother with substance-use disorder. She entered the Michigan foster-care system and by 17 was on the street. She had Tiona at 20, and for three months had no place to live, bouncing between shelters and the homes of friends. With winter coming, she resolved to give up the baby. She typed “free adoption help” into a search engine and clicked on the first link.

Soon she was on the phone with a woman in Virginia named Flossie Green. Green is an adoption facilitator — a scout who connects pregnant women in crisis with adoption agencies across the country, but especially in states with the least oversight. Green told Goins that if she signed adoption papers at an agency in Utah, she’d receive $1,000 to get herself on her feet.

Goins asked for time to think about it, but Green didn’t give her much. “She was so persistent — she must have called me four times in one night,” Goins told me. She agreed to move forward, believing that she would be part of an open adoption, one that allowed her to keep in touch with Tiona as she grew up. “I didn’t want Tiona to have my life,” she says. “But I wanted to be in hers, and they promised me I could.”

The next day, Goins says, Green arranged for her to fly to Utah. She was picked up at the airport by Sandi Quick, the owner of an agency called Brighter Adoptions, and her longtime friend Denise Garza, who had founded an agency called Heart and Soul. Goins did not know it, but Utah had recently revoked Garza’s license and suspended her from the adoption trade because of a raft of violations. Even when the state became aware that Garza was continuing to refer pregnant women to Quick, it took no serious action.

The two women took Goins to McDonald’s, bought three pairs of pajamas for Tiona at a Wal-Mart, and dropped them at a Marriott in Layton. “I didn’t even have to check in,” Goins says. “We just walked right upstairs.”

At lunchtime the next day, Quick drove Goins to a Chili’s to meet a prospective couple from Mississippi and discuss an adoption. Goins asked them to commit to an open arrangement. “This is my first-ever child,” she recalls saying. “Please don’t take her completely from me.” Later, after bringing Tiona back to her hotel room, Goins agonized over the decision and texted Quick that she wanted to back out. Quick told her that she was with a woman in labor and couldn’t speak.

The next day, two women from Quick’s agency — her daughter, Shaylee Budora, and a notary public named Taanya Ramirez — knocked on the hotel-room door. “We’re here to talk to you about the adoption,” Goins recalls Budora saying. Goins told them that she had called things off, but the women acted as if they didn’t hear her. Budora and Ramirez gave her a document and told her where to sign. (Green and Garza dispute Goins’s account. In an emailed statement, Quick said she could not discuss the details of any particular case. “Generally, we take any indication of hesitation from the birth mother very seriously,” she said. “No one affiliated with my agency would ever take consent from a mother who did not fully understand the ramifications.”)

Read the rest of this article at: The Cut

There are many measures of success for a film or TV series. The most easily understandable are viewership metrics. Slightly less quantifiable is the amount of cover stories, articles, think pieces, blogs, social media posts, and articles inspired by a movie or show. Then there’s what I call the Die Hard factor.

For a decade after the release of Die Hard, you could swing a dead cat and hit someone pitching or making “Die Hard in a blank” (a cruise or military vessel, a bus, a stadium, an airplane, a boarding school, a bigger airplane, a military base or military academy, or an airplane that just happened to be Air Force One). Insiders joked that the pitches would eventually circle back to “Die Hard in a building.”

When I began my career, as a network executive in 1993, Moonlighting had the highest Die Hard factor of all TV properties. One season later, everything changed with the immense success of ER. The Die Hard factor on that one was so high that in the following years the airwaves were swamped with shows that were undoubtedly pitched as “ER in a newsroom,” “ER in a police station,” “ER in a law firm,” and even “ER in the White House.”

All of which brings me to Lost, the series that dethroned ER for the Die Hard–factor tiara.

It has been 20 years since Lost ruled the world. I should know: I was there at the beginning, aiding in the development of the show during the filming of the pilot, and then serving as a writer and supervising producer for the first two seasons. And as with so many things that once ruled the world, Lost’s greatest lesson of success has yet to be truly learned…just as it wasn’t learned from Moonlighting, ER, or even Die Hard, for that matter. It is never the high concept that creates the success, but rather the audience’s affection for the characters who live within the high concept.

Die Hard only works because we want put-upon flatfoot John McClane to foil a terrorist plot so he can put his marriage back together. Moonlighting only works because the anarchic, form-breaking writing supported the genre-defining chemistry between David Addison and Maddie Hayes. ER only succeeds because it worked documentary-style, you-are-there televisual magic in the service of Michael Crichton’s unwavering belief in doctors as heroes.

Lost attracted an audience because it had a thrilling, high-budget, high-concept pilot that described an irresistible mystery. That audience came back and stayed because even if the series that followed didn’t always offer satisfying solutions to those mysteries, it most certainly delivered on the promise of a cast of fleshed-out characters whose lives were shot through with compelling incidents, difficult situations, tear-jerking agonies, and shocking destinies.

There is a very sweet, but also very exasperating, time in the life of any artist involved in the creation of a television pilot that goes to series: the months between the completion of the work and the actual release of the work. During that time, the show belongs only to those on the inside, and those with whom they choose to share it in secret.

During the summer before the release of Lost, I carried a DVD of the pilot with me in my computer bag. On occasion, I would put a friend or family member on a variation of the NDA I call a “Friend-DA” and show them its first 10 minutes. Among the many gorgeous shots that J.J. Abrams and his cinematographer Larry Fong concocted for the epic opening plane crash sequence, there’s one of Matthew Fox’s Jack running across the frame to rescue a fellow passenger as all hell explosively breaks loose behind him.

When I showed it to one of my high school friends during a hometown visit and that shot came on, my friend took a moment to catch his breath. Then, completely without irony, he let out the words “What a guy!”

Read the rest of this article at: Vanity Fair

Steven Phillips-Horst had a problem — er, “problem,” depending on who you ask — that plagues many a modern Spotify listener. No matter what song the podcaster and comedian played, whether by Taylor Swift or Celine Dion, Morgan Wallen or the band How to Dress Well, the platform would immediately queue up Sabrina Carpenter’s “Espresso” next.

“How is it that no matter what direction my unique personality takes me in, it leads me back to this same song that I only heard three days ago that I don’t even really like that much?” he asks over the phone, not knowing that the same thing had been happening to me, too.

The disco-inflected soft pop hit, performed by a Polly Pocket-sized former Disney Channel star, was deemed the song of summer nearly as soon as it was released in mid-April. But Phillips-Horst wondered, was that because the song was good? Or, as he proposed on X, was it because of the tantalizing (if unfounded) theory that Carpenter’s label was paying Spotify to force-feed “Espresso” down the throats of listeners the world over?

“It’s not an ‘algorithm,’” he wrote. “The label is paying for radio play in an old school, industry plant kinda way and it’s honestly refreshing. We are so back etc!” Responses flooded in, with hundreds of others saying they too couldn’t escape “Espresso” or other hits from new-ish entries into the pop game, namely Chappell Roan’s “Good Luck, Babe!” and Tommy Richman’s “Million Dollar Baby.”

Read the rest of this article at: Vox

On an evening in December 2023, 43-year-old small business owner Sarah Rosenkranz collapsed in her home in Granbury, Texas and was rushed to the emergency room. Her heart pounded 200 beats per minute; her blood pressure spiked into hypertensive crisis; her skull throbbed. “It felt like my head was in a pressure vise being crushed,” she says. “That pain was worse than childbirth.”

Rosenkranz’s migraine lasted for five days. Doctors gave her several rounds of IV medication and painkiller shots, but nothing seemed to knock down the pain, she says. This was odd, especially because local doctors were similarly vexed when Indigo, Rosenkranz’s 5-year-old daughter, was taken to urgent care earlier that year, screaming that she felt a “red beam behind her eardrums.”

It didn’t occur to Sarah that these symptoms could be linked. But in January 2024, she walked into a town hall in Granbury and found a room full of people worn thin from strange, debilitating illnesses. A mother said her 8-year-old daughter was losing her hearing and fluids were leaking from her ears. Several women said they experienced fainting spells, including while driving on the highway. Others said they were wracked by debilitating vertigo and nausea, waking up in the middle of the night mid-vomit.

None of them knew what, exactly, was causing these symptoms. But they all shared a singular grievance: a dull aural hum had crept into their lives, which growled or roared depending on the time of day, rattling their windows and rendering them unable to sleep. The hum, local law enforcement had learned, was emanating from a Bitcoin mining facility that had recently moved into the area—and was exceeding legal noise ordinances on a daily basis.

Over the course of several months in 2024, TIME spoke to more than 40 people in the Granbury area who reported a medical ailment that they believe is connected to the arrival of the Bitcoin mine: hypertension, heart palpitations, chest pain, vertigo, tinnitus, migraines, panic attacks. At least 10 people went to urgent care or the emergency room with these symptoms. The development of large-scale Bitcoin mines and data centers is quite new, and most of them are housed in extremely remote places. There have been no major medical studies on the impacts of living near one. But there is an increasing body of scientific studies linking prolonged exposure to noise pollution with cardiovascular damage. And one local doctor—ears, nose, and throat specialist Salim Bhaloo—says he sees patients with symptoms potentially stemming from the Bitcoin mine’s noise on an almost weekly basis.

“I’m sure it increases their cortisol and sugar levels, so you’re getting headaches, vertigo, and it snowballs from there,” Bhaloo says. “This thing is definitely causing a tremendous amount of stress. Everyone is just miserable about it.”

Not all data centers make noise. And industry insiders say they have a technical fix for the ones that do, which involves replacing their facilities’ loud air fans with much quieter liquid-based cooling solutions. But some of their touted methods, including “immersion cooling” in oil, are expensive and untested on a large scale.

A representative for Marathon Digital Holdings, the company that owns the mine, did not answer questions about health impacts, but told TIME that it is working to remove the noisy fans from the site. “By the end of 2024, we intend to have replaced the majority of air-cooled containers with immersion cooling, with no expansion required. Initial sound readings on immersion containers indicate favorable results in sound reduction and compliance with all relevant state noise ordinances,” they wrote in an email.

Read the rest of this article at: Time

To understand Priscila Barbosa—the pluck, the ambition, the sheer balls—we should start at the airport. We should start at the precise moment on April 24, 2018, when she concluded, I’m fucked.

Barbosa was just outside customs at New York’s JFK International Airport, 5-foot-1, archetypally pretty even without her favorite Instagram filter. She was flanked by two rolling suitcases stuffed with clothes and Brazilian bikinis and not much else. The acquaintance who had invited her to come from Brazil on a tourist visa, who was going to drive her to Boston? The one who promised to help her get settled, saying that she could make good money like he did, driving for Uber and Lyft?

He’s not answering her texts.

Barbosa was stranded. She cried. She took stock of her belongings: the suitcases, her iPhone, 117 bucks not just in her wallet, but total. She called her mom back in Brazil, but she already knew that her family couldn’t pay for a ticket home. No way was she asking her friends, who had doubted this plan all along; one said she was too old to start over in a new country and, with a whiff of class judgment, insinuated that immigrating was not something their social circle really did.

What now?

Well, Barbosa has a phoenix tattooed on her back. She radiates a game sense of What can I say yes to today? The type of person who, when she and a pal don’t want to splurge on a fancy hotel during a girls trip, swipes right on every guy on Tinder until one joins their bar-crawl and invites them to sleep on his boat. (Says a friend: “Priscila is craaaazy.”) The US government would one day put it more grandly, speaking of Barbosa’s “unique social talents,” calling her “hard-working,” “productive,” and “very organized.”

She knew there was no going back to Brazil but also, deep down, that she didn’t want to, that opportunity was here. “I loved this place”—the US—from nearly the moment she stepped off the plane, she declares. She was 32 years old, college educated, and spoke decent English. She had no choice but to work her way out of this mess.

Barbosa couldn’t have predicted where her striving would end: that she’d become the heavy in a web of fraud. That she’d expose the gig economy’s embarrassing blind spot. That, one day, multibillion-dollar companies like Uber and DoorDash would cry victim. Her victim. Or that she’d fall so far, or that her relationship with Uncle Sam would grow so deeply twisted and codependent.

She did know, that day at JFK Airport, that her doubters back in Brazil would only see one plotline on Instagram: Priscila’s march to victory. Taking a $10 Lyft to a bus station, eyes still puffy from her airport cry, Barbosa aimed her iPhone at the traffic speeding across the Throgs Neck Bridge on a clear spring day. She labeled the video “New York, New York,” and uploaded it onto her Story, ripe with the promise that she was heading somewhere big.

In real life, Barbosa is candid (“I’m a bad liar”). She drops self-deprecating jokes and lets loose big, jagged laughs that sound like a car trying to start. She grew up in Sorocaba, an industrial city of 723,000 people about two hours west of São Paolo. Her dad was an electrician, mom a postal worker. They set their eldest daughter on a path “to be a very educated and polite person”—English lessons and ballet classes. Barbosa loved to mess around on computers. As a teen, she kitted out her home PC with a terabyte of memory and an Nvidia processor so she could play Counter-Strike and World of Warcraft. She also hung out at a local cyber café, where she and a few other gamers formed a tournament team called the BR Girls (“BR” for Brazil). Offscreen, high school was miserable. She was bullied for being a teacher’s pet, for being “chunky,” for being terrible at sports. When a few boys showed romantic interest in her, she turned them down for fear it was a prank.

Barbosa studied IT at a local college, taught computer skills at elementary schools, and digitized records at the city health department. She also became a gym rat (“I’ve had to fight for the perfect body my whole life”) and started cooking healthy recipes. In 2013, she spun this hobby into a part-time hustle, a delivery service for her ready-made meals. When orders exploded, Barbosa ramped up to full-time in 2015, calling her business Fit Express. She hired nine employees and was featured in the local press. She was making enough to travel to Walt Disney World, party at music festivals, and buy and trade bitcoin. She happily imagined opening franchises and gaining a solid footing in the upper-middle class.

Read the rest of this article at: Wired