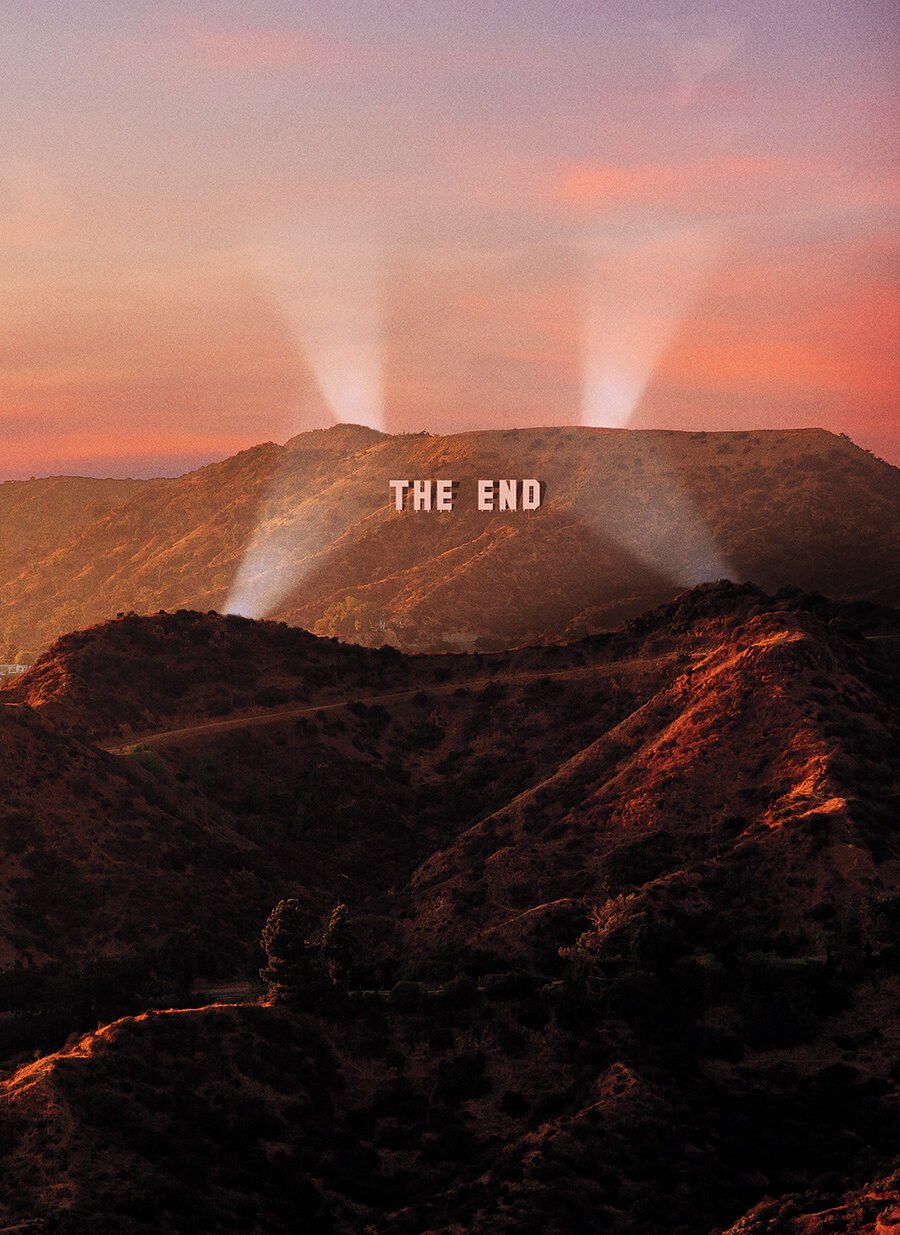

In 2012, at the age of thirty-two, the writer Alena Smith went West to Hollywood, like many before her. She arrived to a small apartment in Silver Lake, one block from the Vista Theatre—a single-screen Spanish Colonial Revival building that had opened in 1923, four years before the advent of sound in film.

Smith was looking for a job in television. She had an MFA from the Yale School of Drama, and had lived and worked as a playwright in New York City for years—two of her productions garnered positive reviews in the Times. But playwriting had begun to feel like a vanity project: to pay rent, she’d worked as a nanny, a transcriptionist, an administrative assistant, and more. There seemed to be no viable financial future in theater, nor in academia, the other world where she supposed she could make inroads.

For several years, her friends and colleagues had been absconding for Los Angeles, and were finding success. This was the second decade of prestige television: the era of Mad Men, Breaking Bad, Homeland, Girls. TV had become a place for sharp wit, singular voices, people with vision—and they were getting paid. It took a year and a half, but Smith eventually landed a spot as a staff writer on HBO’s The Newsroom, and then as a story editor on Showtime’s The Affair in 2015.

I first spoke with Smith in August of last year, four months into the strike called by the Writers Guild of America against the members of the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP), the biggest Hollywood studios. In 2013, she’d begun to develop the idea for what would become Dickinson, a gothic, at times surreal comedy based on the life of the poet, Emily. “I realized you could do one of those visceral, sexy, dangerous half hours but make it a period piece,” she said. “I was never trying to write some middle-of-the-road thing.” She sold the pilot and a plan for at least three seasons to Apple in 2017; she would be the showrunner, and the series had the potential to become one of the flagship offerings of the company’s streaming service, which had not yet launched.

Looking back, Smith sometimes marvels that Dickinson was made at all. “It centers an unapologetic, queer female lead,” she said. “It’s about a poet and features her poetry in every episode—hard-to-understand poetry. It has a high barrier of entry.” But that was the time. Apple, like other streamers, was looking to make a splash. “I mean, they made a show out of I Love Dick,” Smith said, referring to the small-press cult classic by Chris Kraus, adapted into a 2016 series for Amazon Prime Video. “That doesn’t happen because people are using profit as their bottom line.”

In fact, they weren’t. The streaming model was based on bringing in subscribers—grabbing as much of the market as possible—rather than on earning revenue from individual shows. And big swings brought in new viewers. “It’s like a whole world of intellectuals and artists got a multibillion-dollar grant from the tech world,” Smith said. “But we mistook that, and were frankly actively gaslit into thinking that that was because they cared about art.”

Read the rest of this article at: Harpers

B ILLIE EILISH IS AT the bottom of a pool, held down by a large black weight attached to her shoulders. She is not, to put it mildly, enjoying herself. “I was basically waterboarding myself for six hours straight,” the 22-year-old superstar tells me later. “If I’m not suffering somehow, I don’t feel good about what I’m doing.”

Eilish is wearing baggy black pants beneath a pair of shorts, a button-down shirt over a thermal long-sleeve, a striped tie, arm warmers, a variety of silver rings, and a goth-studded bracelet, plus that anchor on her shoulders. She’s been submerging herself over and over for two minutes at a time, holding her breath for the duration, while the photographer William Drumm snaps her sinking beneath a white wooden door. Her eyes are completely open during those 120 seconds, with no goggles or nose plugs to help.

We’re at a soundstage in Santa Clarita, California, on a chilly, rainy February afternoon. Eilish is surrounded by a team of nearly 40 people. There’s a stylist, her management, and caterers standing next to a table filled with snacks and ginger shots. There are men aiding her with an oxygen mask she uses between plunges, with one of them shouting “Three breaths away!” to count down to the moment she goes under. Maggie Baird, Eilish’s mom, nervously sits at the edge of the pool, watching her daughter put her body through the kind of pain experienced divers would struggle with.

The point of all of this suffering? Eilish is shooting the cover for her third album, Hit Me Hard and Soft (out May 17). “If there’s one thing about me, it is I will put myself through hell and back for the shot,” she tells me. “I’ve always been like that, and I will continue to be like that. A lot of my artwork is painful physically in a lot of ways, and I love it. Oh, my God, I live for it.”

Less than 48 hours ago, Eilish won Song of the Year at the Grammys for “What Was I Made For?,” her delicate, devastating hit from the Barbie soundtrack. After the Grammys, she stayed up until 7:30 the next morning, crashed until one, ate some avocado toast, then dyed her hair completely black, saying goodbye to her red roots, in preparation for today’s shoot.

It’s been a weird stretch of time for Eilish. “What Was I Made For?” was way bigger than she anticipated; the past few months have been a blur of awards shows, and she’s ready to disappear for a while, till the album hits, at least. “Bro, nobody can get enough of me,” she tells me. “Every second of every day is Barbie, Barbie, Barbie, Barbie, Barbie, which is great, but as soon as the Oscars are over and I lose, I’m going the fuck away. I’m literally gone.”

But she doesn’t lose: On March 10, she finds herself onstage at the Dolby Theater, accepting the award for Best Original Song — the same award she won in 2022 for “No Time to Die,” from the last James Bond movie — and becoming the youngest double-Oscar winner in history. “I had a nightmare about this last night,” she told the crowd. “I just didn’t think this would happen. I wasn’t expecting this. I feel so incredibly lucky and honored.”

Read the rest of this article at: Rolling Stone

Reading, while not technically medicine, is a fundamentally wholesome activity. It can prevent cognitive decline, improve sleep, and lower blood pressure. In one study, book readers outlived their nonreading peers by nearly two years. People have intuitively understood reading’s benefits for thousands of years: The earliest known library, in ancient Egypt, bore an inscription that read The house of healing for the soul.

But the ancients read differently than we do today. Until approximately the tenth century, when the practice of silent reading expanded thanks to the invention of punctuation, reading was synonymous with reading aloud. Silent reading was terribly strange, and, frankly, missed the point of sharing words to entertain, educate, and bond. Even in the 20th century, before radio and TV and smartphones and streaming entered American living rooms, couples once approached the evening hours by reading aloud to each other.

But what those earlier readers didn’t yet know was that all of that verbal reading offered additional benefits: It can boost the reader’s mood and ability to recall. It can lower parents’ stress and increase their warmth and sensitivity toward their children. To reap the full benefits of reading, we should be doing it out loud, all the time, with everyone we know.

Read the rest of this article at: The Atlantic

The more recent history of copyright in music cannot be separated from the rise and rapid obsolescence of technologies for the recording and transmission not just of sound but of text and pictures, too. Each of these evanescent devices sparked panic among stakeholders, whose partly successful resistance to change explains much of the tangle we are now in—and the high valuation of Bruce Springsteen’s life work.

The first tech alarm to sound out loud was prompted by the introduction of video-cassette recorders, which made it possible for individuals to record protected material broadcast on television without paying an additional license fee. The film industry sought to stamp out such “piracy” by targeting the manufacturers of the V.C.R.s, whose presumptive liability was founded on the novel and unusual tort of “contributory copyright infringement.”

The case was appealed to the Supreme Court, which decided in the end that Sony’s Betamax recorders were legitimate devices, since they could be used for non-infringing purposes as well as for “piracy.” So, having failed to block sales of the technology, the film industry took a different path. Studios started manufacturing videocassettes themselves, and made them available through commercial lending libraries (very much akin to the Circulating Libraries of nineteenth-century England), and later by subscription to a mail-order lending service. As in many other circumstances described in this book, the wider dissemination of copyright material almost certainly made more money for the content owners than narrower regulation would have done.

The greatest perceived threat to financial stakeholders in the culture industry in the later years of the twentieth century came from Tim Berner-Lee’s invention of the Internet.

However, rented videocassettes could themselves be copied by ordinary folk with a double-deck V.C.R. and a stock of blank tapes. The Motion Picture Association of America mounted a vigorous and noisy campaign to make the duplication of a licensed cassette, or the duplication of self-recorded cassettes taken from a broadcast, a criminal offense. The campaign succeeded: it resulted in the Warning from the FBI that used to figure as the first frame of movies that could be bought or rented in cassette or D.V.D. format until those media themselves disappeared.

However, the greatest perceived threat to financial stakeholders in the culture industry in the later years of the twentieth century came from Tim Berner-Lee’s invention of the World Wide Web. Initially designed as a tool to allow scientists to share their work, it quickly became a means for distributing perfect copies of text, and then sound and image files, at a marginal cost that was, for the first time, zero to the copier, if not to the planet.

Publishers feared their entire business would be destroyed, and music companies were in an even greater panic. Peer-to-peer technologies were devised to enable perfect reproductions of music recordings to be made and shared widely—thus rendering C.D.s obsolete overnight. The music industry tried to pursue the companies that hosted these services or facilitated the Internet connections that allowed them to function. In an effort to insulate themselves from this type of liability, the Internet service providers (I.S.P.s) successfully lobbied Congress for a “safe harbor,” which eventually came in 1998, under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, or D.M.C.A.

Read the rest of this article at: Literary Hub

In 2022, Penguin Random House wanted to buy Simon & Schuster. The two publishing houses made up 37 percent and 11 percent of the market share, according to the filing, and combined they would have condensed the Big Five publishing houses into the Big Four. But the government intervened and brought an antitrust case against Penguin to determine whether that would create a monopoly.

The judge ultimately ruled that the merger would create a monopoly and blocked the $2.2 billion purchase. But during the trial, the head of every major publishing house and literary agency got up on the stand to speak about the publishing industry and give numbers, giving us an eye-opening account of the industry from the inside. All of the transcripts from the trial were compiled into a book called The Trial. It took me a year to read, but I’ve finally summarized my findings and pulled out all the compelling highlights.

I think I can sum up what I’ve learned like this: The Big Five publishing houses spend most of their money on book advances for big celebrities like Britney Spears and franchise authors like James Patterson and this is the bulk of their business. They also sell a lot of Bibles, repeat best sellers like Lord of the Rings, and children’s books like The Very Hungry Caterpillar. These two market categories (celebrity books and repeat bestsellers from the backlist) make up the entirety of the publishing industry and even fund their vanity project: publishing all the rest of the books we think about when we think about book publishing (which make no money at all and typically sell less than 1,000 copies).

But let’s dig into everything they said in detail.

In my essay “Writing books isn’t a good idea” I wrote that, in 2020, only 268 titles sold more than 100,000 copies, and 96 percent of books sold less than 1,000 copies. That’s still the vibe.

Q. Do you know approximately how many authors there are across the industry with 500,000 units or more during this four-year period?

A. My understanding is that it was about 50.

Q. 50 authors across the publishing industry who during this four-year period sold more than 500,000 units in a single year?

A. Yes.

— Madeline Mcintosh, CEO, Penguin Random House US

The DOJ’s lawyer collected data on 58,000 titles published in a year and discovered that 90 percent of them sold fewer than 2,000 copies and 50 percent sold less than a dozen copies.

In my essay “No one will read your book,” I said that publishing houses work more like venture capitalists. They invest small sums in lots of books in hopes that one of them breaks out and becomes a unicorn, making enough money to fund all the rest.

Turns out, they agree!

Every year, in thousands of ideas and dreams, only a few make it to the top. So I call it the Silicon Valley of media. We are angel investors of our authors and their dreams, their stories. That’s how I call my editors and publishers: angels… It’s rather this idea of Silicon Valley, you see 35 percent are profitable; 50 on a contribution basis. So every book has that same likelihood of succeeding.— Markus Dohle, CEO, Penguin Random House

Read the rest of this article at: The Alysian