It is a familiar story: a small group of animals living in a wooded grassland begin, against all odds, to populate Earth. At first, they occupy a specific ecological place in the landscape, kept in check by other species. Then something changes. The animals find a way to travel to new places. They learn to cope with unpredictability. They adapt to new kinds of food and shelter. They are clever. And they are aggressive.

In the new places, the old limits are missing. As their population grows and their reach expands, the animals lay claim to more territories, reshaping the relationships in each new landscape by eliminating some species and nurturing others. Over time, they create the largest animal societies, in terms of numbers of individuals, that the planet has ever known. And at the borders of those societies, they fight the most destructive within-species conflicts, in terms of individual fatalities, that the planet has ever known.

This might sound like our story: the story of a hominin species, living in tropical Africa a few million years ago, becoming global. Instead, it is the story of a group of ant species, living in Central and South America a few hundred years ago, who spread across the planet by weaving themselves into European networks of exploration, trade, colonisation and war – some even stowed away on the 16th-century Spanish galleons that carried silver across the Pacific from Acapulco to Manila. During the past four centuries, these animals have globalised their societies alongside our own.

It is tempting to look for parallels with human empires. Perhaps it is impossible not to see rhymes between the natural and human worlds, and as a science journalist I’ve contributed more than my share. But just because words rhyme, it doesn’t mean their definitions align. Global ant societies are not simply echoes of human struggles for power. They are something new in the world, existing at a scale we can measure but struggle to grasp: there are roughly 200,000 times more ants on our planet than the 100 billion stars in the Milky Way.

Read the rest of this article at: Aeon

Before the sea started taking house-sized bites out of Nyangai, this small tropical island off the coast of Sierra Leone hummed with activity. I first visited in 2013 while documenting the construction of a school on a neighboring island. It was a cloudless day in April. A group of teenagers was busy setting up a sound system for a party. Old men chatted and smoked in the shade of palm trees. Children chased each other through the maze of sandy lanes while a constant traffic of roughly hewn wooden boats plied the surrounding waters.

The silhouettes of coconut palms and June plum trees dominated the island’s profile, and beneath them stood clusters of neat mud-and-thatch homes. The beach that ringed the island was so white it hurt the eyes, the water a limpid green. I couldn’t stay for long, but Nyangai left a deep impression.

In December of the following year, I caught another glimpse of the island, this time while flying over it in a United Nations helicopter delivering emergency supplies to a nearby island at the height of the West African Ebola epidemic. From the air, it looked fragile, its curved, slender form barely 50 meters wide in places. I didn’t know it then, but the island I was looking at was a mere stub of what it had once been.

Nyangai (also spelled Nyankai and Yankai on some maps) is shrinking at an alarming rate, its sandy soil eroded by an increasingly destructive sea. In the span of a human lifetime, the vast majority of its land has disappeared, and most of its population has fled. Those who remain, many of whose families have called Nyangai home for generations, are squeezed into an ever-decreasing patch of sand. Within a few years, many fear, the island may disappear altogether.

Returning to Nyangai in 2023, a decade after my first visit, I found the place almost unrecognizable. From a satellite image, I had seen that the island had been split in half by the sea, leaving two bean-shaped patches of land separated by a wide gulf. But as my boat approached, I could see only one: in the time since Google had last updated its satellite image in 2018, an entire village of several hundred people had vanished.

“The water is eating the island,” says Tewoh Koroma, a mother of six who lost her home to flooding in September 2023. “We already fled from the water once and now we’re getting flooded again. The water is following us.”

Over the past decade, each new storm or flood has prompted more to leave. Some head for the country’s coastal capital, Freetown, or to other towns on the mainland, while others move to nearby islands. Nyangai’s leaders say there were once more than 500 homes here. Today there are fewer than 100.

Read the rest of this article at: Hakai Magazine

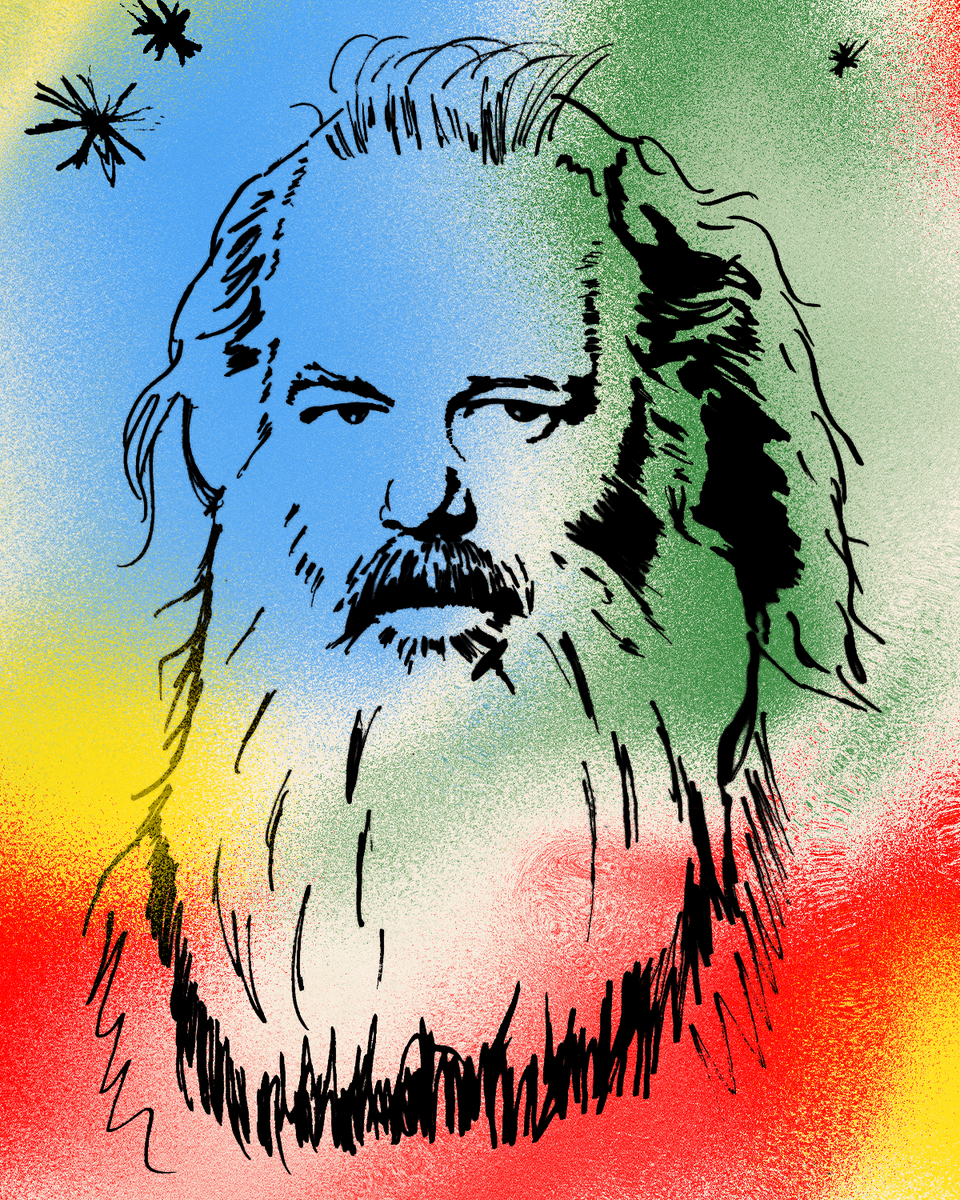

The Rick Rubin method: It’s not for everyone. Warm-voiced, flowing, bearded like a deity, the legendary record producer (nine Grammys) is about mindset. He’s about essence. He’s hands-off, allowing the possibilities to manifest, and then abruptly, disorientingly, hands-on, demanding take after take of a guitar solo or vocal line. And if you are, for example, a late-stage rock star from the postwar slums of Birmingham, England, it might all tend to make you a bit grumpy. “I still don’t know what he did,” Geezer Butler, the Black Sabbath bassist and lyricist, told SiriusXM a few years ago, recalling Rubin’s work on Sabbath’s 2013 comeback album, 13. “It was a weird experience … He played us our very first album, and he said, ‘Cast your mind back to then, when there was no such thing as heavy metal or anything like that—and pretend it’s the follow-up album to that,’ which is a ridiculous thing to think.”

Read the rest of this article at: The Atlantic

On the morning of June 24, 1993, Yale University Professor David Gelernter arrived at his office on the fifth floor of the computer science department. He had just returned from vacation and was carrying a large stack of unopened mail. One book-shaped package was in a plastic ziploc — he thought it looked like a PhD dissertation. As he unzipped it, pungent white smoke poured out, followed by what he later described as a “terrific flash.” He never heard the bang. Shrapnel shot into his eyes, hands and torso, as well as the steel file cabinets around him. A fire ignited and triggered the sprinklers in the ceiling, which began to soak his books and papers.

Gelernter, as he later wrote in his memoir, had been “blown up.” He was the 14th person attacked by a serial killer who was still then at large and known only as the “Unabomber.” From 1978 to 1995, Theodore John Kaczynski, fueled by an ideology that sought to bring about the destruction of modern technological life and a return to primitive ways, murdered three people and injured 23 in a brutal mail-bombing campaign. Gelernter’s lungs and other internal organs were damaged, he lost the vision in his right eye and most of his right hand was destroyed. But he survived.

Around two years later, another letter from Kaczynski arrived at the computer sciences department for Gelernter. No bomb this time — just a typewritten message in which Kaczynski explained the attack was provoked by Gelernter’s most recent book: a speculative work of nonfiction titled “Mirror Worlds.”

Back in 1991 when the book was first published, just over 1% of Americans were using the internet. But Gelernter claimed computing was about to revolutionize life on Earth. “This book describes an event that will happen someday soon,” he wrote in the opening line. “You will look into a computer screen and see reality. Some part of your world — the town you live in, the company you work for, your school system, the city hospital — will hang there in a sharp color image, abstract but recognizable, moving subtly in a thousand places.”

In essence, Gelernter believed that every aspect of life could soon be modeled in a parallel digital simulation. Everything happening in our lived reality would be tracked and monitored and fed into software “by a steady rush of new data pouring in through cables” to create a high-fidelity real-time digital representation of the world and all of its pulsing, swarming and sensuous qualities. This would be like Mark Zuckerberg’s metaverse on steroids: our exact world, our very lives, all digital. And you could view, manipulate, experience and interact with this mirror world, like a child with a dollhouse. A dashboard for reality.

Read the rest of this article at: Noema

I didn’t expect Steve Martin to be funny. Sure, it was his skewwhiff sensibility that made The Jerk, The Man With Two Brains, LA Story and Bowfinger so deliriously inspired. And he was comedy’s first double-platinum-record-selling, stadium-touring megastar; he began wearing a white suit on stage only so that he could be seen by fans in the cheap seats several postcodes away. He crafted riotous slapstick crescendos in All of Me and Dirty Rotten Scoundrels and displayed a literary flair even at his silliest. No one who has seen Roxanne, the modern-day interpretation of Edmond Rostand’s Cyrano de Bergerac that found Martin investing his comedy with emotional weight for the first time, will dispute the Edward-Lear-like genius of the line “earn more sessions by sleeving”.

But when he isn’t starring in the crime-comedy series Only Murders in the Building, which he co-created, he is a serious sort. He writes plays, makes bluegrass records, collects art – knows everything about art, in fact. (He once sold an Edward Hopper for almost $27m.) Now, he is the subject of Steve! (Martin), a two‑part, three-hour-plus survey of his life and career from the Oscar-winning documentary supremo Morgan Neville. The chance today of lols looks low.

But blow me down if the first thing out of his mouth isn’t a gag.

All I have done is ask him and Neville, who are speaking to me from separate locations via a video call, whether they can hear me clearly. “I’m not sure,” says Martin. “It sounds like you have some kind of British accent on mine.” And we’re off.

The 78-year-old actor is in his New York City apartment, a heaving bookcase and mint-coloured sofa behind him, peering at his screen through brown-framed glasses. His hair is ceramic-white and looks as soft as cotton wool; his friend and comedy partner Martin Short once likened him to “a page in a colouring book that hasn’t been coloured in yet”.

Why did he agree to make the documentary? “You can’t analyse your own life and work,” Martin says. “I know what it looks like on the inside: a big mess, a big jumble. But how about from the outside?” What did he learn? “Well, I’ve only seen it once. I’ll know what to think when other people look at it. The one thing I did after I watched it was to call Morgan and say: ‘Shouldn’t you have mentioned the awards?’”

Neville is a lifelong fan. “I didn’t totally get what Steve was doing when I was a kid, but there’s an absurdity you respond to,” he says from his home in Pasadena, California. “Once you grow up, you see the sophistication as well.” What did he need from Martin for the documentary to work? “He had to be open. And it became clear from our initial meeting that he was genuinely curious about his own life.”

Read the rest of this article at: The Guardian