On a friendly stroll somewhere in Colorado in the summer of 2004, Steve Jobs asked Walter Isaacson if he would consider writing his biography. Isaacson, a journalist, academic, and policymaker who was then CEO of the Aspen Institute, an influential think tank, had just published a six-hundred-odd-page study of Benjamin Franklin, and was at work on another about Albert Einstein. “My initial reaction was to wonder, half jokingly,” Isaacson later reflected, “whether he saw himself as the natural successor in that sequence.”

Isaacson did not take Jobs up on the offer until 2009, when he learned that the Apple boss was dying of pancreatic cancer. When Steve Jobs was published in 2011, just a couple of weeks after its subject passed away, it became clear that during his years of reporting the book, Isaacson had been convinced of what had first struck him only in jest. The front cover, designed with input from Jobs himself, featured a black-and-white photograph of the tech guru gazing knowingly at the camera, his thumb on his chin in contemplation: here is Jobs as world-historic genius, Silicon Valley successor to Franklin and Einstein. The narrative resonated with a public still enthralled by the misfit, college-dropout tech genius. That year was a kind of high-water mark for techno-optimism; the Arab Spring protests were still bringing democracy to the Middle East one tweet at a time; Google, with its ping-pong tables and massage rooms, was still widely considered the best place to work in the world. Isaacson’s portrait of Steve Jobs played to this market, selling around 380,000 copies in its first week.

Read the rest of this article at: The Drift

Last summer, AdamYedidia, a user on a Web forum called LessWrong, published a post titled “Chess as a Case Study in Hidden Capabilities in ChatGPT.” He started by noting that the Internet is filled with funny videos of ChatGPT playing bad chess: in one popular clip, the A.I. confidently and illegally moves a pawn backward. But many of these videos were made using the original version of OpenAI’s chatbot, which was released to the public in late November, 2022, and was based on the GPT-3.5 large language model. Last March, OpenAI introduced an enhanced version of ChatGPT based on the more powerful GPT-4. As the post demonstrated, this new model, if prompted correctly, could play a surprisingly decent game of chess, achieving something like an Elo rating of 1000—better than roughly fifty per cent of ranked players. “ChatGPT has fully internalized the rules of chess,” he asserted. It was “not relying on memorization or other, shallower patterns.”

This distinction matters. When large language models first vaulted into the public consciousness, scientists and journalists struggled to find metaphors to help explain their eerie facility with text. Many eventually settled on the idea that these models “mix and match” the incomprehensibly large quantities of text they digest during their training. When you ask ChatGPT to write a poem about the infinitude of prime numbers, you can assume that, during its training, it encountered many examples of both prime-number proofs and rhyming poetry, allowing it to combine information from the former with the patterns observed in the latter. (“I’ll start by noting Euclid’s proof, / Which shows that primes aren’t just aloof.”) Similarly, when you ask a large language model, or L.L.M., to summarize an earnings report, it will know where the main points in such documents can typically be found, and then will rearrange them to create a smooth recapitulation. In this view, these technologies play the role of redactor, helping us to make better use of our existing thoughts.

But after the advent of GPT-4—which was soon followed by other next-generation A.I. models, including Google’s PaLM-2 and Anthropic’s Claude 2.1—the mix-and-match metaphor began to falter. As the LessWrong post emphasizes, a large language model that can play solid novice-level chess probably isn’t just copying moves that it encountered while ingesting books about chess. It seems likely that, in some hard-to-conceptualize sense, it “understands” the rules of the game—a deeper accomplishment. Other examples of apparent L.L.M. reasoning soon followed, including acing SAT exams, solving riddles, programming video games from scratch, and explaining jokes. The implications here are potentially profound. During a talk at M.I.T., Sébastien Bubeck, a Microsoft researcher who was part of a team that systematically studied the abilities of GPT-4, described these developments: “If your perspective is, ‘What I care about is to solve problems, to think abstractly, to comprehend complex ideas, to reason on new elements that arrive at me,’ then I think you have to call GPT-4 intelligent,” he said.

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

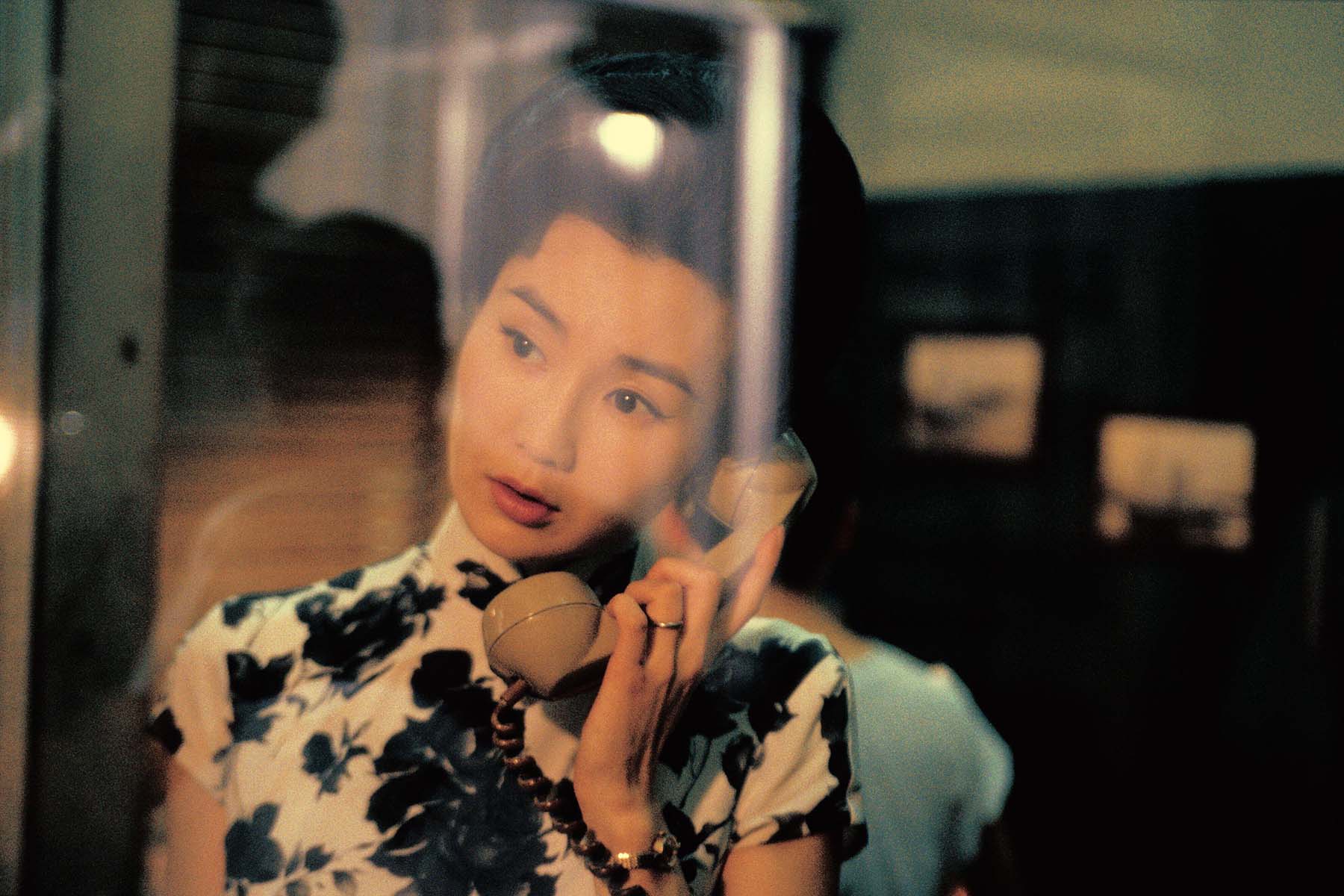

After a series of returns to my hometown over a fifteen-year period, a trip in 2017 confirmed a truth I’d been avoiding: Hong Kong did not feel like the same place I had known as a child. Between failed attempts to get by with my faltering Cantonese and an inability to recognize the once-beloved neighbourhoods that had defined my childhood, I felt like a stranger in my own home.

On my last day, after saying goodbye to my grandparents in their apartment, I looked back at them standing by their door. They seemed frail and dejected, and my grandfather turned away while holding back tears; ever since I moved away, I had felt we shared a mutual understanding that each goodbye could be the last time we would see each other. The painful memory would often reappear whenever I reminisced about my time in Hong Kong. I’d try to avoid feeling nostalgic at all, because I didn’t want their pained faces polluting my happy memories of home.

Since that time, people have been leaving the city in droves. After a wave of protests against national security legislation in 2019, Hong Kong experienced a steep population decline. Thousands of residents have emigrated to places like Taiwan, Canada, and the UK in recent years. I wonder if, like me, they wax nostalgic about a home they no longer recognize.

Read the rest of this article at: The Walrus

The Sheats-Goldstein House, located high up in Beverly Hills, is a James Lautner–designed marvel, with a tennis court, a koi pond, and, from the living room, a sweeping view of Los Angeles, just now easing into spring. Though the home’s owner, courtside fixture Jimmy Goldstein, pledged in 2016 to someday donate the house to LACMA, photos of Goldstein with various luminaries—Bill Clinton, Karl Lagerfeld, Drake—still line the walls, and a well-worn CD collection (Pure Pacha Summer 2014, Club St. Tropez 2006) sits stacked in one corner of the living room. This is where they shot the scene in The Big Lebowski in which Jeff Bridges sprawls on the modernist couch, drugged into a dream by a particularly potent White Russian. Now Roger Federer is sitting right about where The Dude sat, taking in the view.

He hasn’t seen the film, he says, though he heard it was a “big success”—he’s more familiar with the location because he once shot something here for a Champagne brand, which is a very Roger Federer thing to say. In person, he is slightly taller than you might think, his eyes a touch more hazel-y. At 42, he still moves with the same grace and efficiency as he did when he was a professional tennis player, though when he and I stand up from the couch where we’ve been talking, we both make the exact same involuntary groan. (Nevermind that Federer has played in more than 1,500 professional tennis matches, and won 20 Grand Slams, and I’m just a guy who watched a sampling of those victories from a variety of reclined postures—it was the same exact sound.) “My back was fine yesterday,” Federer says, laughing and patting it gently.

Last night, Federer attended the Academy Awards ceremony for the second time. (The first time was in 2016, “when Leo won for The Revenant”—another very Roger Federer thing to say.) Even before his retirement, on a tear-filled September evening at the 2022 Laver Cup in London, Federer has had an uncommon interest, for a professional athlete, in the world outside of sports. He has long been a fixture on red carpets from Wimbledon to the Met Gala. “I know some players who do hotel, club, hotel, club, room service, watching sports all day, and that’s it,” Federer says. This was not, and is not, Federer’s way. He is a social guy, and a curious one. Since retiring, in part because of an injury to his left knee that required multiple surgeries, he has traveled frequently from his home in his native Switzerland—Tokyo, Thailand, South Africa—with his wife and four kids, and tried his hand at design, most recently with the California eyewear brand Oliver Peoples, with whom he is releasing a sleek line of sunglasses this week.

One and a half years into his new life, he is reflective but still seemingly powered by whatever potent mix of ease and focus he relied upon as a player. “Just staying in the narrow tennis mind is not enough,” Federer says. “I feel like going out and meeting people and doing different things to me is very appealing, even though I used to dread red carpets and small talk and all that stuff.”

Read the rest of this article at: GQ

The public’s love-hate relationship with the media has tipped toward just hate in recent years, but professional news media, especially local news, are foundational to democracy. America’s constitutional framers took the media’s role as informers and educators of the public so seriously, they not only carved out freedom of the press in the Bill of Rights, but also subsidized the circulation of periodicals in the newborn republic, a federal practice that continued until relatively recently. The news business’s slow death spiral should alarm us across political divides.

Several crises are besieging the media simultaneously: People are increasingly dropping news from their information diets, ad-dollar-reliant business models continue to dry up, outlets and websites are closing, and the rise of artificial intelligence threatens to put yet more pressure on human newsgathering. The world isn’t going to end anytime soon, but mass media as we know it just might.

Consider the evidence: While the United States is enjoying a strong post-pandemic recovery and a surge in job growth, nearly every sector of the news media is taking a beating. The industry shed 20,000 jobs last year, with local news outlets hardest hit: An average of 2.5 newspapers closed each week, compared to two a week in 2022. Journalism’s heavy-hitters also took plenty of blows, with layoffs taking place at NPR, MSNBC, The Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Vox, Buzzfeed, and others.

Vice News—the once-influential, freewheeling Gen-X hipster mag that adopted a scolding “everything-is-problematic” persona once urban Millennials took over in the 2010s—died an ignoble death in February. Sports Illustrated, seemingly omnipresent a few decades ago, recently spit out poorly written “pink slime” articles by fake reporters created by generative AI before laying off nearly its entire staff. And in a move that bitterly sums up the state of things, media mogul Jimmy Finkelstein just killed The Messenger.

The professional messengers still standing are panicking, and with good reason. Yet big journalism’s bosses and gatekeepers seem unwilling to meet the moment. Last month, I was a panelist at a journalism conference at Columbia University to lament the sad state of the news biz in the lead-up to the 2024 election. Insiders there insisted on wagging fingers at the usual suspects: Google and Facebook for cannibalizing their content, billionaires with midlife crises who buy newspapers like they might a new Lambo and just as easily discard them, or Fox News for polluting the news ecosystem with dumbed-down and partisan-first content.

Read the rest of this article at: Compact