If you had to capture Silicon Valley’s dominant ideology in a single anecdote, you might look first to Mark Zuckerberg, sitting in the blue glow of his computer some 20 years ago, chatting with a friend about how his new website, TheFacebook, had given him access to reams of personal information about his fellow students:

Zuckerberg: Yeah so if you ever need info about anyone at Harvard

Zuckerberg: Just ask.

Zuckerberg: I have over 4,000 emails, pictures, addresses, SNS

Friend: What? How’d you manage that one?

Zuckerberg: People just submitted it.

Zuckerberg: I don’t know why.

Zuckerberg: They “trust me”

Zuckerberg: Dumb fucks.

That conversation—later revealed through leaked chat records—was soon followed by another that was just as telling, if better mannered. At a now-famous Christmas party in 2007, Zuckerberg first met Sheryl Sandberg, his eventual chief operating officer, who with Zuckerberg would transform the platform into a digital imperialist superpower. There, Zuckerberg, who in Facebook’s early days had adopted the mantra “Company over country,” explained to Sandberg that he wanted every American with an internet connection to have a Facebook account. For Sandberg, who once told a colleague that she’d been “put on this planet to scale organizations,” that turned out to be the perfect mission.

Read the rest of this article at: The Atlantic

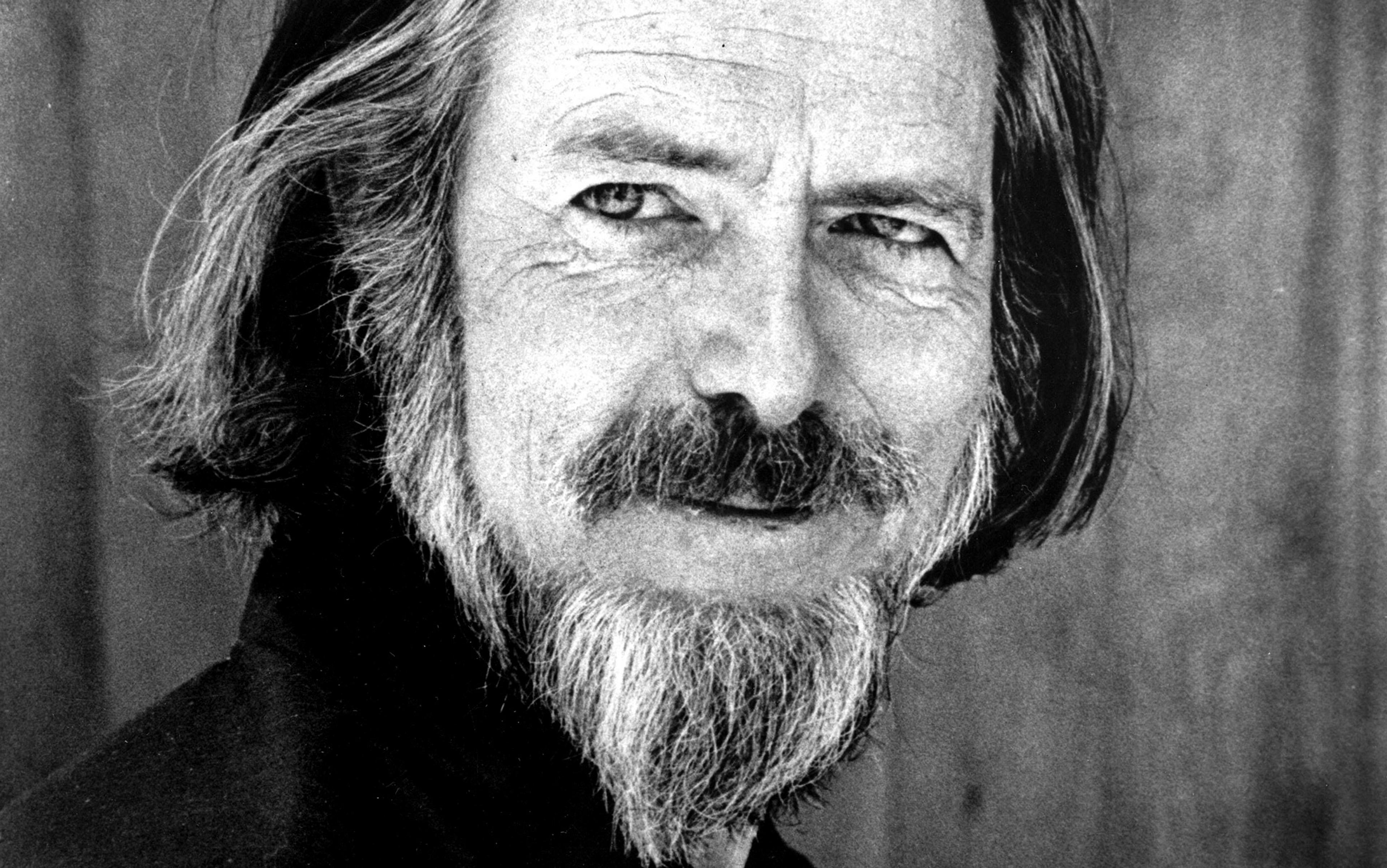

On 16 November 1973, Joan Watts received a phone call that began in the worst possible way: ‘Are you sitting down?’ Her father, the English writer and philosopher Alan Watts, had died during the previous night, as a storm lashed his home in Marin County, California. His heart had failed at the age of just 58. Watts’s third wife, Mary Jane Yates King or ‘Jano’, blamed his experiments with breathing techniques intended to achieve samadhi, or absorptive contemplation: he had left his body, she thought, without knowing how to come back. Joan took a different view. Her father had become lost in work and alcohol. He had finally ‘had enough’, she concluded, and had ‘checked out’.

It seems fitting that, even in the manner of his dying, Watts should divide opinion. He frequently did so in life. Born in 1915, in Chislehurst in Kent, Watts moved to the United States with his first wife shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War. Living first in New York, he ended up making his home on the West Coast, where he joined the likes of Allen Ginsberg and Gary Snyder as a leading light of the 1960s counterculture.

Countless young Americans heard Watts speak, on campuses and on the radio, extolling the wisdom of the East and informing them in wry, patrician English that the ideals into which their parents and teachers had indoctrinated them were, by comparison, empty. Life did not have to be ‘about’ something or ‘going’ somewhere, any more than the point of playing or listening to a Bach prelude was to get to the end as quickly and efficiently as possible. One’s aim instead should be to tackle the monstrous case of mistaken identity from which so many modern Westerners suffered: each believing themselves to be a small, anxious self when underneath lay a glorious greater Self, entirely at one with the rest of reality.

Read the rest of this article at: Aeon

In 2017, Simon McCarthy-Jones wrote an article about schizophrenia for The Conversation. The piece, he jokes, got read by more than two people, which, as an academic—he’s an associate professor of clinical psychology at Trinity College Dublin—was a thrill. Shortly thereafter, however, he found himself “just gripped by the iron claws of Facebook,” looking over and over again to see who had liked his article, who had commented on it. It was “grabbing my attention, making me think, ‘Check Facebook! Check Facebook!’” he said in a recent video call from his office in Ireland.

Was his thinking being covertly, coercively controlled by external forces (in this case, a big tech company)? The experience got him wondering just what “free thought” actually was. And so he started wading into the murky waters of the psychological, philosophical, cultural, and legal assumptions about what constitutes thought—and how it could remain truly free.

Read the rest of this article at: Nautilus

Sir Lucian Grainge, the chairman and C.E.O. of Universal Music Group, the largest music company in the world, is curious, empathetic, and, if not exactly humble, a master of the humblebrag. His superpower is his humanity. A sixty-three-year-old Englishman, who was knighted in 2016 for his contributions to the music industry and has topped Billboard’s Power 100 list of music-industry players several times in the past decade, Grainge is compact and a bit chubby, with alert eyes behind owlish glasses. He isn’t trying to be noticed. He presides over a public company worth more than fifty billion dollars, but he could be a small-business owner who sells music in a London shop, as did his father, Cecil. On earnings calls, Grainge can sound more like a London taxi dispatcher than a chief executive. But woe to those who mistake his European civility for a lack of competitive fire. “He is so deceptive with that little kind face and those little glasses,” Doug Morris, the previous chairman of UMG, told the Financial Times in 2003, when he was still Grainge’s boss. “Behind them, he is actually a killer shark.” In 2011, Grainge devoured Morris’s job.

As UMG’s leader, he has solidified the dominance of Universal, the largest of the Big Three label groups, helping it to overtake Warner Music and Sony. More than half of Spotify’s twenty most streamed artists of all time are signed to UMG. But Grainge is also the consummate music man, with forty-five years of experience on both the publishing and the label sides of the business. He oversees a long list of formerly independent labels, including Interscope, Republic, Capitol, Motown, and Island. “Lucian’s like the league commissioner,” Monte Lipman, who founded Republic with his brother Avery, told me. Don Was, the head of Blue Note, UMG’s storied jazz label, said, “He’s the smartest motherfucker in the music business, period. He can operate in the artistic world, and he can operate in the financial world, which are two very different beasts.”

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

Is Sundance Playing It Safe?

This year’s edition of Sundance concluded yesterday, and, though I saw some films of great merit there, I also found myself thinking about the peculiar cinematic economy that the festival fosters. This was partly because, the day before Sundance ended, I’d taken part in a panel discussion about the great French critic Serge Daney (1944-92), as part of the Film at Lincoln Center’s series devoted to his work. The series celebrates the first appearance in English of his 1983 book, “Footlights”; the book’s translator, Nicholas Elliott, was also on the panel, along with Maddie Whittle, who programmed the series with him. At one point, our discussion turned to an interview with Daney that I’d read when it first came out, in 1977, and which contains an observation that now strikes me forcefully: “Until now, the big difference between France and the U.S.A. has been this: there is no bridge between American ‘underground’ cinema and the film industry, while there has always been one in France.” These days, there is such a bridge here: think of Greta Gerwig, Barry Jenkins, and the Safdie brothers. (Indeed, it came into existence not too long after Daney was speaking, as one can see in the careers of Spike Lee and Jim Jarmusch.) And Sundance, which celebrated its fortieth anniversary this year, is one of the bridge’s crucial ramps. But the bridge, it turns out, runs both ways: the prospect of success has altered the very nature of independent filmmaking. Some filmmakers, working without commercial constraints, demonstrate great artistic originality; others make, in effect, calling cards, proving their mastery of the codes of commercial cinema, albeit on a scant budget. Much of the Sundance sweet spot lies in the intersection: enough originality to attract notice and enough populist touches to attract audiences.

The needle swings from year to year. Last year veered toward originality, with such offerings as “All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt” and “Passages.” For me, this year’s viewings seemed less original, though this may reflect what I was able to see. As always, I didn’t attend the festival in person and relied on the version that is streamed for the press, but, this time, online viewings didn’t start until seven days into the eleven-day festival. Several of the films I was most eagerly anticipating weren’t available, and there was less time for viewing what was available. Much of what I was able to see seemed a little slighter in innovation than last year’s crop. Nonetheless, I saw a pair of films that, if they get distribution, will be releases of major importance.

As young independent filmmakers go, Nathan Silver is already a veteran, with nine features to his name since his first, from 2009, which he made when he was twenty-five. But his latest, “Between the Temples,” reveals a striking new vein of thought and invention, both in his career and in American filmmaking at large. The film’s scintillating cleverness is exemplified by a single detail, a sublime indirection: The movie’s protagonist, Ben Gottlieb (Jason Schwartzman), is the cantor of a synagogue in upstate New York. He’s on a first date with a woman named Leah (Pauline Chalamet), whom he met on the Jewish dating service Jdate. Raising her glass, Leah says, “L’chaim”—or, rather, “L’haim,” completely missing the distinctive Hebrew uvular consonant. For a second, I was shocked that Silver had the chutzpah to cast an actress whose pronunciation was so inadequate in the role of a Jewish woman. Moments later, though, Leah confesses to Ben that she’s not Jewish but “a hundred per cent Protestant.” Silver knew what he was doing; namely, taking viewers aback to match Ben’s own surprise in the moment.

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker