On Jan. 17, media conglomerate Condé Nast revealed that it would be laying off staff at the online music publication Pitchfork and merging the website with men’s magazine GQ. “Today we are evolving our Pitchfork team structure by bringing the team into the GQ organization,” wrote Anna Wintour, chief content officer at the venerable company that also publishes The New Yorker, Vogue, and Vanity Fair, in a memo to staffers that was first reported by Semafor and obtained by Rolling Stone. After 28 years and countless album reviews — scored, with mock-scientific precision, on Pitchfork’s signature 0.0 to 10.0 scale — the music-criticism source that came of age with the internet had suffered its first major setback. The site isn’t over (as of now, its future under GQ is unsure), but on social media, voices from around the music journalism sphere mourned it like it was.

The announcement hit with a particular sense of finality for me because I was one of the dozen people let go in the current round of layoffs, along with editor-in-chief Puja Patel and executive editor Amy Phillips, who has tirelessly steered Pitchfork’s news coverage and beyond for more than 18 years. In a music and media landscape where mass layoffs have become routine — look at the sharp cuts at Bandcamp, Tidal, and Spotify in recent months alone — the purge at Pitchfork wasn’t exactly a surprise. My role as senior staff writer, running the gamut from reviews to investigative journalism and essentially taking on long-term assignments that others on staff didn’t have time to do, has always felt like it was too good to last. Jill Mapes, one of our two brilliant features editors who were both also laid off this week, has referred to her job as “being on a Ferris wheel at closing time, just waiting for them to yank me down,” and that about it sums it up for me, too. But as Pitchfork Union has noted in a statement, Condé Nast CEO Roger Lynch announced last November that he planned to cut about 5 percent of CN’s workforce, and after about a month of limbo, company representatives told union bargaining members before Christmas that there would be no layoffs at Pitchfork. Whoops.

Read the rest of this article at: Rolling Stone

In a 1985 essay on Susan Sontag, her friend the translator and poet Richard Howard noted that one of Sontag’s preferred techniques of fiction was the mise en abime—the repetition of forms and elements such that “the story is inlaid within the story.” These doublings and digressions-in-digressions suggest an “infinite regress” that thwarts such conventional pleasure of reading as moving forward step-by-step toward an assured ending—or even knowing exactly what’s going on and who is whom. The technique of mis-en-abiming, Howard argued, was logically accompanied by tactics of hybridization and fragmentation that Sontag, along with writers she admired like Donald Barthelme and Guy Davenport, had learned from the French critic Roland Barthes, who in his last works (translated by Howard) broke open genre conventions in texts partaking of memoir and essay, organized, or disorganized, around arbitrary clusters of themes, by a craft of disorder.

Sontag’s sentences, too, were crumbly, short, and disjointed, tending toward aphorism and separated by a certain degree of parataxis, following the pattern of Barthes, Emile Cioran (also translated by Howard) and other postwar European “masters of the elliptical and the oblique.” Behind these figures stood the higher, or deeper, master of European intellectual modernity, Friedrich Nietzsche. Howard, who had known Sontag for decades, recalled that in the early ’60s he’d spotted scrawled on her notes for a talk “NIETZSCHE—my hero!” like an adolescent writing the name of a crush.

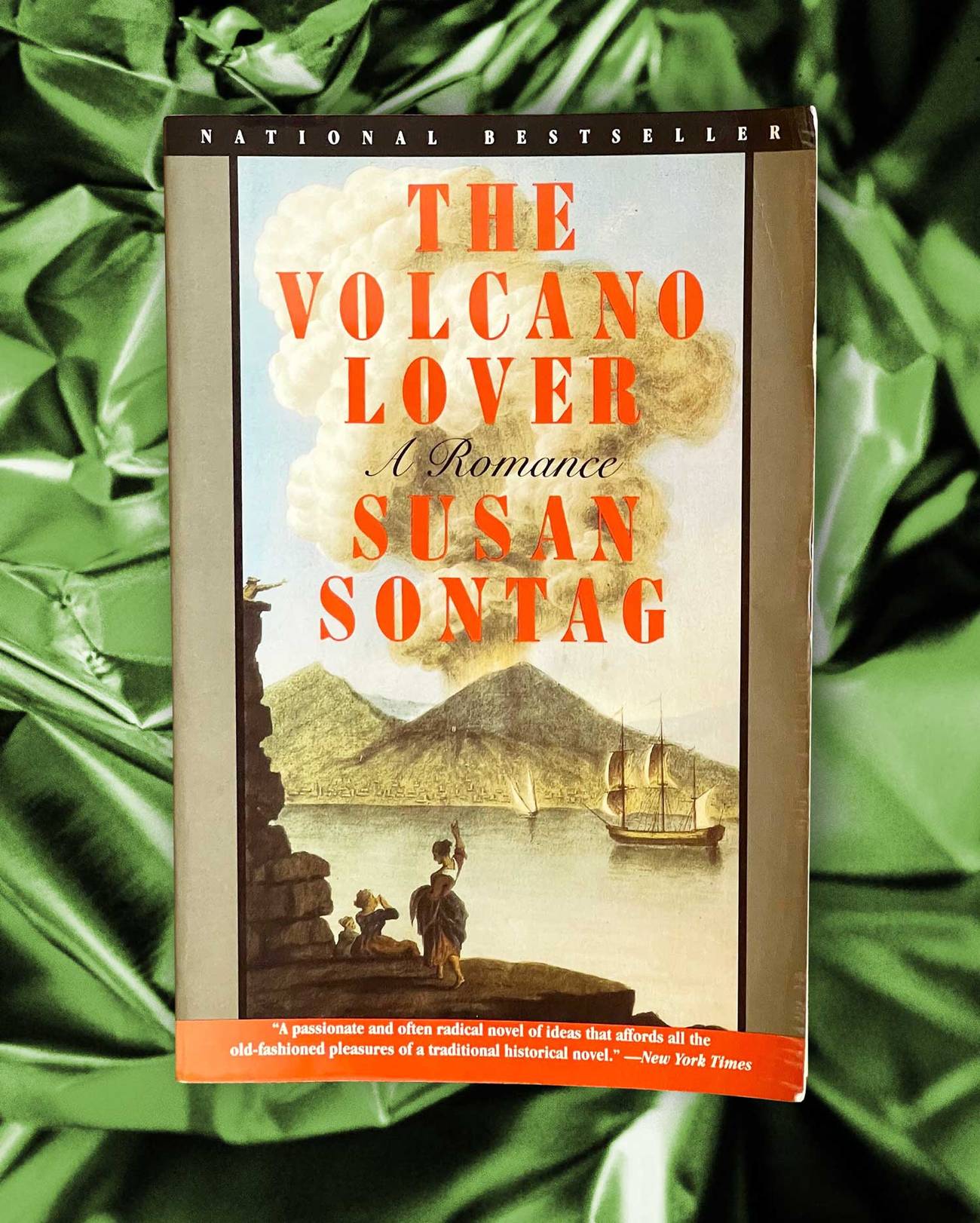

Seven years later, with the publication of her novel The Volcano Lover (1992), Sontag showed that she was capable of something much more worthwhile than another whirl of European decadence—a brilliant, polyphonic, moving (often funny! sexy! sad!) work in which different thoughts and different forms of writing play—like the voices of her characters and multiple narrators—together in a pageant, an opera of a book.

Read the rest of this article at: Tablet

Alastair Humphreys is a British adventurer and author. He has bicycled around the world, walked across southern India, rowed across the Atlantic, run six marathons in the Sahara and trekked 1,000 miles through the Empty Quarter. He was named one of National Geographic’s adventurers of the year in 2012. He is the author of 16 books, including “Local: A Search For Nearby Nature And Wildness,” from which this essay is adapted.

“Instructions for living a life:

Pay attention.

Be astonished.

Tell about it.“

—Mary Oliver

“In the end, I think that a single mountain range is enough exploration for an entire lifetime.”

—Rickey Gates

For more than 20 years, my favorite thing has been to leave here behind, with all its ties and routines. To hit the road and make my way to there. I get twitchy being in one place for too long. I have been lucky enough to cycle a lap of the planet, row and sail the Atlantic, hike across southern India and trek over Arctic ice and Arabian sands. A spin of the globe and off I go on the open road. Home was for family, friends and real life, not for exploration and adventure.

Read the rest of this article at: Noema

Anyone who has learned a second language will have made an exhilarating (and yet somehow unsettling) discovery: there is never a one-to-one correspondence in meaning between the words and phrases of one language and another. Even the most banal expressions have a slightly different sense, issuing from a network of attitudes and ideas unique to each language. Switching between languages, we may feel as if we are stepping from one world into another. Each language seemingly compels us to talk in a certain way and to see things from a particular perspective. But is this just an illusion? Does each language really embody a different worldview, or even dictate specific patterns of thought to its speakers?

In the modern academic context, such questions are usually treated under the rubrics of ‘linguistic relativity’ or the ‘Sapir-Whorf hypothesis’. Contemporary research is focused on pinning down these questions, on trying to formulate them in rigorous terms that can be tested empirically. But current notions concerning connections between language, mind and worldview have a long history, spanning several intellectual epochs, each with their own preoccupations. Running through this history is a recurring scepticism surrounding linguistic relativity, engendered not only by the difficulties of pinning it down, but by a deep-seated ambivalence about the assumptions and implications of relativistic doctrines.

Read the rest of this article at: Aeon

If you were a young person living in London in the early 1970s and you were looking for a bargain, the word of Nicholas Saunders was something close to holy scripture. Whatever you sought, Saunders had the answer. If you wanted to start an anarchist squat or self-publish a Trotskyist pamphlet, you consulted Nicholas Saunders. If you wanted to know how much a gram of cocaine should cost, or where to get free legal advice if you were arrested, you consulted Nicholas Saunders. If you just wanted to find out how to unblock a drain without calling a plumber, which supermarkets were cheaper for which goods, or how to fly all the way to India on a ticket to Frankfurt, you consulted Nicholas Saunders.

A tall young man with a wild beard that gave him the look of a shaman, Saunders was obsessed with documenting how the new global counterculture was changing the ancient city around him. In 1970, at the age of 32, he self-published his findings in a slim but dense guidebook called Alternative London. The book was testament to Saunders’ belief that information should be made available to all, and that this information should be rigorously tested. For the section on abortions, Saunders had a friend phone up each provider in the city, in the process uncovering a London-wide scam of clinics that marketed themselves as “cheap” but in reality were charging over double the non-profit rate. By 1974, Alternative London and its subsequent revised editions had sold close to 200,000 copies and become an underground bible.

Read the rest of this article at: The Guardian