In the ordinary way of things, when people say that they are giving up, they are usually referring to something like smoking, or alcohol, or chocolate, or any of the other anaesthetic pleasures of everyday life; they are not, on the whole, talking about suicide (though people do tend to want to give up only their supposedly self-harming habits). Giving up certain things may be good for us, and yet the idea of someone just giving up is never appealing. Like alcoholics who need everybody to drink, there tends to be a determined cultural consensus that life is, and has to be, worth living (if not, of course, actually sacred).

There are, to put it as simply as possible, what turn out to be good and bad sacrifices (and sacrifice creates the illusion – or reassures us – that we can choose our losses). There is the giving up that we can admire and aspire to, and the giving up that profoundly unsettles us. What, for example, does real hope or real despair require us to relinquish? What exactly do we imagine we are doing when we give something up? There is an essential and far-reaching ambiguity to this simple idea. We give things up when we believe we can change; we give up when we believe we can’t.

All the new thinking, like all the old thinking, is about sacrifice, about what we should give up to get the lives we should want. For our health, for our planet, for our emotional and moral wellbeing – and, indeed, for the profits of the rich – we are asked to give up a great deal now. But alongside this orgy of improving self-sacrifices – or perhaps underlying it – there is a despair and terror of just wanting to give up. A need to keep at bay the sense that life may not be worth the struggle, the struggle that religions and therapies and education, and entertainment, and commodities, and the arts in general are there to help us with. For more and more people now it seems that it is their hatred and their prejudice and their scapegoating that actually keeps them going. As though we are tempted more than ever by what Nietzsche once called “a will to nothingness, a counter-willan aversion to life, a rebellion against the most fundamental presuppositions of life”.

The abiding disillusionment with politics and personal relationships, the demand for and the fear of free speech, the dread and the longing for consensus and the coerced consensus of the various fundamentalisms has created a cultural climate of intimidation and righteous indignation. It is as if our ambivalence about our aliveness – about the feeling alive that, however fleeting, sustains us – has become an unbearable tension and needs to be resolved. So even though we cannot, as yet, imagine or describe our lives without the idea of sacrifice, and its secret sharer, compromise, the whole notion of what we want and can get through sacrifice is less clear; both what we think we want and what we are as yet unaware of wanting. The formulating of personal and political ideals has become either too assured or too precarious. And the whole notion of sacrifice depends upon our knowing what we want.

Read the rest of this article at: The Guardian

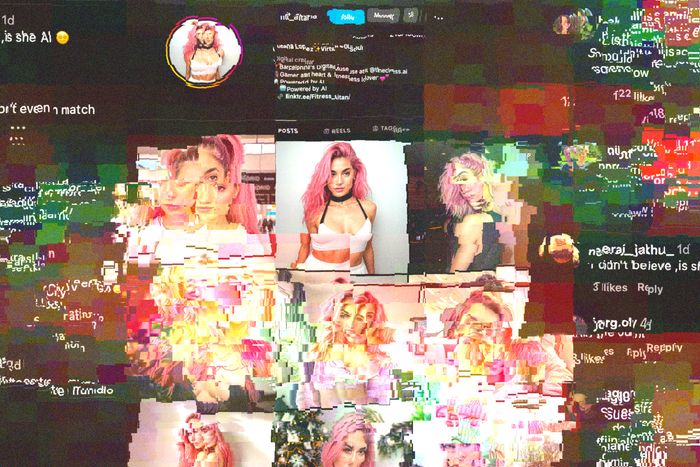

For a preview of how AI will collide with creative industries, look to advertising. Amazon, Google, and Meta have all started encouraging advertisers to use AI tools to generate ad copy and imagery, promising high performance, lower costs, and super-specific targeting. Now, brands are paying to advertise with AI-generated virtual influencers — synthetic characters that can offer at least some promotional juice at a fraction of the cost. According to the FT, influencers are concerned:

Aitana is a “virtual influencer” created using artificial intelligence tools, one of the hundreds of digital avatars that have broken into the growing $21bn content creator economy.

Their emergence has led to worry from human influencers their income is being cannibalised and under threat from digital rivals … But those behind the hyper-realistic AI creations argue they are merely disrupting an overinflated market.

“We were taken aback by the skyrocketing rates influencers charge nowadays. That got us thinking, ‘What if we just create our own influencer?’” said Diana Núñez, co-founder of the Barcelona-based agency The Clueless, which created Aitana. “The rest is history. We unintentionally created a monster. A beautiful one, though.”

The marriage makes sense. In a purely descriptive, nonjudgmental sense, AI produces inauthentic content; in a purely descriptive, nonjudgmental sense, the advertising industry is premised on inauthenticity. Advertising takes all the interesting, thorny, unsettling issues raised by generative AI and folds them into the same simple, eminently answerable question it always asks: Does this stuff sell products?

Read the rest of this article at: New York Magazine

Creating art isn’t just a pastime, it is a way of living. But how can you nurture a more artistic existence? Artists share their advice on how to be more creative.

It doesn’t matter if you can’t draw

Helen Cammock was one of the winners of the Turner prize in 2019 and says she didn’t have artistic tendencies as a child, despite being the daughter of an art teacher. “Just because you can’t draw something in a representative, representational way, it doesn’t mean that you’re not creative,” she says. Cammock, who lives in north Wales, works across “film, photography, print, performance, writing and text”. She is hopeful that art lessons at school have changed to be less focused on representational drawing and painting.

It’s never too late to create

Cammock was 35 when she began studying art – after a 10-year career as a social worker. She says it is important to keep challenging ourselves by trying new things. “The older we get as adults, the less we feel comfortable taking risks. If we think about the kinds of things we did when we were children and tested out when we were teenagers, somehow it gets squeezed out of you and risk-taking is not a space that you can inhabit. There is something about enabling yourself to try things and not have expectations about what you will produce.” Cammock is now having trumpet lessons: “I will never be a wonderful trumpet player but it is important to me that I open myself to new things all the way through my life.” Anne Ryan, an Irish artist who works in paint, ceramics and sculpture, has taken up tap dancing for a similar reason. “I’m crap at it but I come out glowing and feeling like I have spread a little bit of love,” she says. That energy feeds into her art.

Read the rest of this article at: The Guardian

One of the things that moved me many years ago to become a psychiatrist was a desire to acquire a deeper understanding of human nature. People all share basic desires and fears, whether they have a mental disorder or not, but these desires and fears are often more intense, and therefore better illustrated, in the presence of a mental illness. Perhaps no desire is more universal than the desire for happiness, made more concrete and felt more urgently when a person is struggling psychologically. Such cases help to show why happiness is such an elusive aim for any person – and what a wiser objective would be.

‘I’m hoping you’ll be able to help me doctor,’ Mark says. ‘I’ve been depressed for ages and can’t go on like this any longer.’ Mark is an amalgam of patients with bipolar disorder whom I’ve seen over the years. He is indeed depressed, and this episode has been longer and more severe than the previous ones. He last felt well about a year ago. He explains that things were going very well and then, quite suddenly, he crashed. On further questioning, it becomes apparent that he had not been merely doing well before the onset of his depression; in fact, he was a bit high before he went down, although he doesn’t view it that way. He insists that the bubbly, confident and expansive 40-year-old who is happy to embark on risky sexual and financial adventures is his normal self, the real Mark.

Bipolarity shifts points of reference to the extent that one may end up forgetting what a normal mood feels like. Some sufferers swing from depression to mania and back without stopping in the middle. I sympathise with Mark: if I had bipolar disorder, I, too, would see my disinhibited and exuberant self as the real me, and the sad and anxious self as the sick me. The problem is that the ‘happiness’ of mania is unsustainable. Mark’s ambition to return to that state of mind, and to stay there indefinitely, is never going to be realised. (In fact, even the assumption that people in a state of mania feel consistently happy is wrong; mania is often irritable, impatient and dysphoric.) With some luck, treatment will stabilise and modulate his mood fluctuations, but it will not be able to make him permanently happy.

The happiness that someone like Mark misses is unreal and unhealthy. He needs to learn to want a different type of relative happiness – that is, a state of reasonable contentment, with intermittent joy and pain, which, unlike the myth of a permanent bliss, can potentially be achieved. Switching from one goal to the other will involve a process of acceptance and recognition that pain is natural and normal, and not always a symptom to be treated.

Read the rest of this article at: Psyche

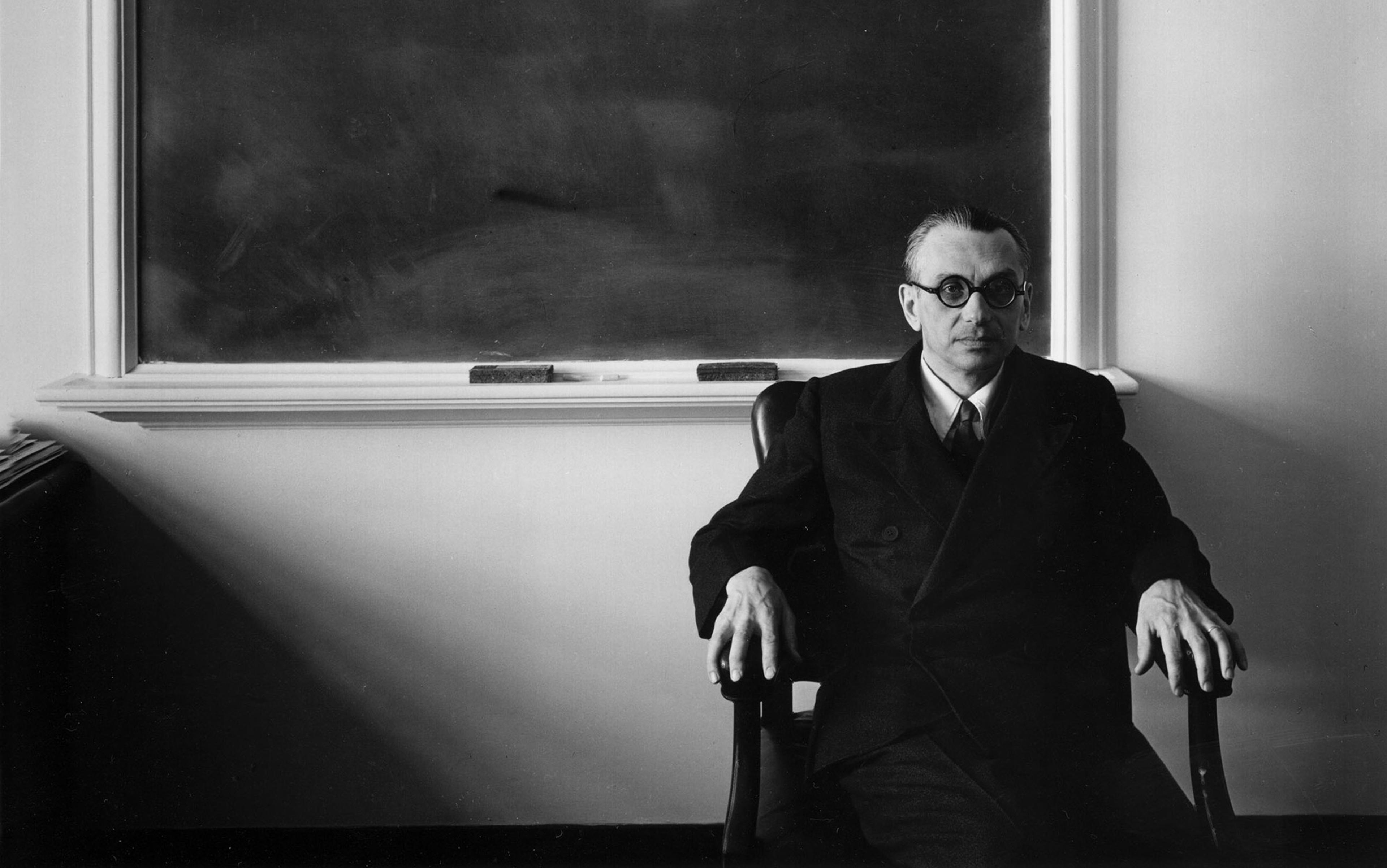

As the foremost logician of the 20th century, Kurt Gödel is well known for his incompleteness theorems and contributions to set theory, the publications of which changed the course of mathematics, logic and computer science. When he was awarded the Albert Einstein Prize to recognise these achievements in 1951, the mathematician John von Neumann gave a speech in which he described Gödel’s achievements in logic and mathematics as so momentous that they will ‘remain visible far in space and time’. By contrast, his philosophical and religious views remain all but hidden from view. Gödel was private about these, publishing nothing on this subject during his lifetime. And while scholars have grappled with his ontological proof of God’s existence, which he circulated among friends towards the end of his life, other tenets of his belief system have received no significant discussion. One of these is Gödel’s belief that we survive death.

Why did he believe in an afterlife? What argument did he find persuasive? It turns out that a relatively full answer to these questions is buried in four lengthy letters written to his mother, Marianne Gödel, in 1961, to whom he makes the case that they are destined to meet again in the hereafter.

Before exploring Gödel’s views on the afterlife, I want to recognise his mother as the silent heroine of the story. Although most of Gödel’s letters are publicly accessible via the digital archives of the Wienbibliothek im Rathaus (Vienna City Library), none of his mother’s letters are known to have survived. We possess only his side of their conversation, left to infer what she said from his replies. This creates a mystique when reading his letters, as if one were provided a Platonic dialogue with all the lines removed, except for those uttered by Socrates. Although we lack her own words, we owe a debt of gratitude to Marianne Gödel. For, without her curiosity and independence of thought, we would have one less resource in understanding her famous son’s philosophy.

Thanks to Marianne’s direct question about Gödel’s belief in an afterlife, we get his mature views on the matter. She asked him for this in 1961, a time when he was in top intellectual form and thinking extensively about philosophical topics at the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) in Princeton, New Jersey, where he had been a full professor since 1953 and a permanent member since 1946. The nature of the exchange compelled Gödel to detail his views in a thorough and accessible manner. As a result, we have (with some supplementation) the equivalent of Gödel’s full argument for belief in an afterlife, intentionally aimed at comprehensively satisfying his mother’s questions, which appear in the series of letters to Marianne from July through to October 1961. While Gödel’s unpublished philosophical notebooks present a space in which he actively worked out views and experimented through often gnomic aphorisms and remarks, Gödel wanted these letters to be understandable and to provide a definitive answer to an earnest enquiry. And because the correspondence was private, he did not feel the need to hide his true views, which he might have done in more formal academic settings and among his colleagues at the IAS.

Read the rest of this article at: Aeon