There’s a scene in the new apocalypse thriller Leave the World Behind in which a 27-year-old character describes the show Friends as “almost nostalgic for a time that never existed”. Her lip curls with contempt as she says it, and not just for the show itself. Because if Friends was guilty of selling a lie — with its shiny, sanitised, notably non-diverse depiction of life in New York — wasn’t its millennial fanbase equally guilty of buying it? When she sneers at Friends, she’s really sneering at herself, for falling for it.

In this, she represents an entire generation’s penchant for repudiating the culture that shaped it. Nostalgia is resentment-tinged among millennials, for whom being downtrodden and disenfranchised has become something of a permanent calling card. Five years ago, it was a truth universally acknowledged that we would be the first cohort to do worse economically than our parents. Crushed by unmanageable college debt, unable to buy houses or start families, and burned out by the endless demands of side hustling, millennials were surely the unluckiest generation.

The only problem with this universally-acknowledged truth is that, actually, it’s not true: a fact that’s become inescapable this year. “Millennials, as a group, are not broke—they are, in fact, thriving economically,” wrote Jean Twenge in The Atlantic in April. “Since the mid-2010s, Millennials on the whole have made a breath-taking financial comeback.” The data backs this up: although the wealth gap between rich and poor persists within the millennial generation, and the housing market makes home ownership slightly more challenging than it used to be, all the catastrophising seems to have been premature. Millennials are doing fine.

And yet, their image as uniquely put-upon has proved persistent — especially among millennials themselves. Once you’ve entrenched a generational narrative, people will continue to identify with it, irrespective of how things may have evolved. For the same reason that the children of the Sixties styled themselves as anti-establishment hippies from the comfort of their corporate offices, millennials have struggled to let go of the sense that there’s something uniquely difficult about their lives — even as they cruise comfortably into middle age, buying homes, having kids, accumulating assets. But if we’re doing well by every available metric, how can we explain the fact that we feel like such losers?

Read the rest of this article at: Unherd

In early September, La Zambra, a five-star golf resort near Málaga, in southern Spain, hosted a jamboree for an organization called the Supercar Owners Circle. At the event, wealthy car enthusiasts—almost exclusively men—gathered to show off their vehicles, gawp at other people’s, and drive the mountainous roads of Andalusia faster than was strictly legal. The gathering, which took place over a long weekend, was by invitation only. Admission, along with room and board, cost about nine thousand dollars. “Only the most prestigious and uncompromising supercars of past and present are eligible,” the club’s Web site warned. “The final decision lies with the admission board, which consists of both S.O.C. members and external automotive specialists.”

On the Thursday evening that I arrived at La Zambra, in an Uber, the parking lot was already half full. Each car had been allotted a particular spot. I introduced myself to a thirtysomething Brit with a Midlands accent, who was walking the lot, occasionally taking photographs. He called himself Zak, but preferred not to give his surname. He’d arrived in a bright-blue McLaren 765LT Coupe, an aggressive-looking sports car with a four-litre engine for which he had paid five hundred and seventy thousand dollars. McLaren was his favorite make of car, he explained, because “everything is British”; he also loved “the sound and the vibration” he experienced when driving the coupe. Many supercar collectors rarely take their vehicles out of the garage, but Zak liked to use his for daily chores. “I go to the shops in it,” he said. “I stick it in a multistory car park. All right, I do a couple of laps before I find a spot—but I use it.”

Many of the cars in the lot were considerably more expensive and rarer than Zak’s McLaren, and he admitted that he thought himself fortunate to have been invited. I asked him if he coveted any of the other cars. He pointed out a Bugatti Chiron, with lusciously curved side panels and a cartoonishly large grille. The Chiron costs at least three million dollars, and all the cars of its limited run of five hundred have been sold. “I quite fancy a Bugatti,” Zak said.

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

Cultural upheavals can be a riddle in real time. Trends that might seem obvious in hindsight are poorly understood in the present or not fathomed at all. We live in turbulent times now, at the tail end of a pandemic that killed millions and, for a period, reordered existence as we knew it. It marked, perhaps more than any other crisis in modern times, a new era, the world of the 2010s wrenched away for good.

What comes next can’t be known – not with so much war and political instability, the rise of autocrats around the world, and the growing plausibility of a second Donald Trump term. Within the roil – or below it – one can hazard, at least, a hypothesis: a change is here and it should be named. A rebellion, both conscious and unconscious, has begun. It is happening both online and off-, and the off is where the youth, one day, might prefer to wage it. It echoes, in its own way, a great shift that came more than two centuries ago, out of the ashes of the Napoleonic wars.

The new romanticism has arrived, butting up against and even outright rejecting the empiricism that reigned for a significant chunk of this century. Backlash is bubbling against tech’s dominance of everyday life, particularly the godlike algorithms – their true calculus still proprietary – that rule all of digital existence.

Read the rest of this article at: The Guardian

Noam Chomsky rose to fame in the 1960s and even now, in the 21st century, he is still considered one of the greatest intellectuals of all time. His prominence as a political analyst on the one hand, and theoretical linguist on the other, simply has no parallel. What remains unclear is quite how the two sides of the great thinker’s work connect up.

When I first came across Chomsky’s linguistic work, my reactions resembled those of an anthropologist attempting to fathom the beliefs of a previously uncontacted tribe. For anyone in that position, the first rule is to put aside one’s own cultural prejudices and assumptions in order to avoid dismissing every unfamiliar belief. The doctrines encountered may seem unusual, but there are always compelling reasons why those particular doctrines are the ones people adhere to. The task of the anthropologist is to delve into the local context, history, politics and culture of the people under study – in the hope that this may shed light on the logic of those ideas.

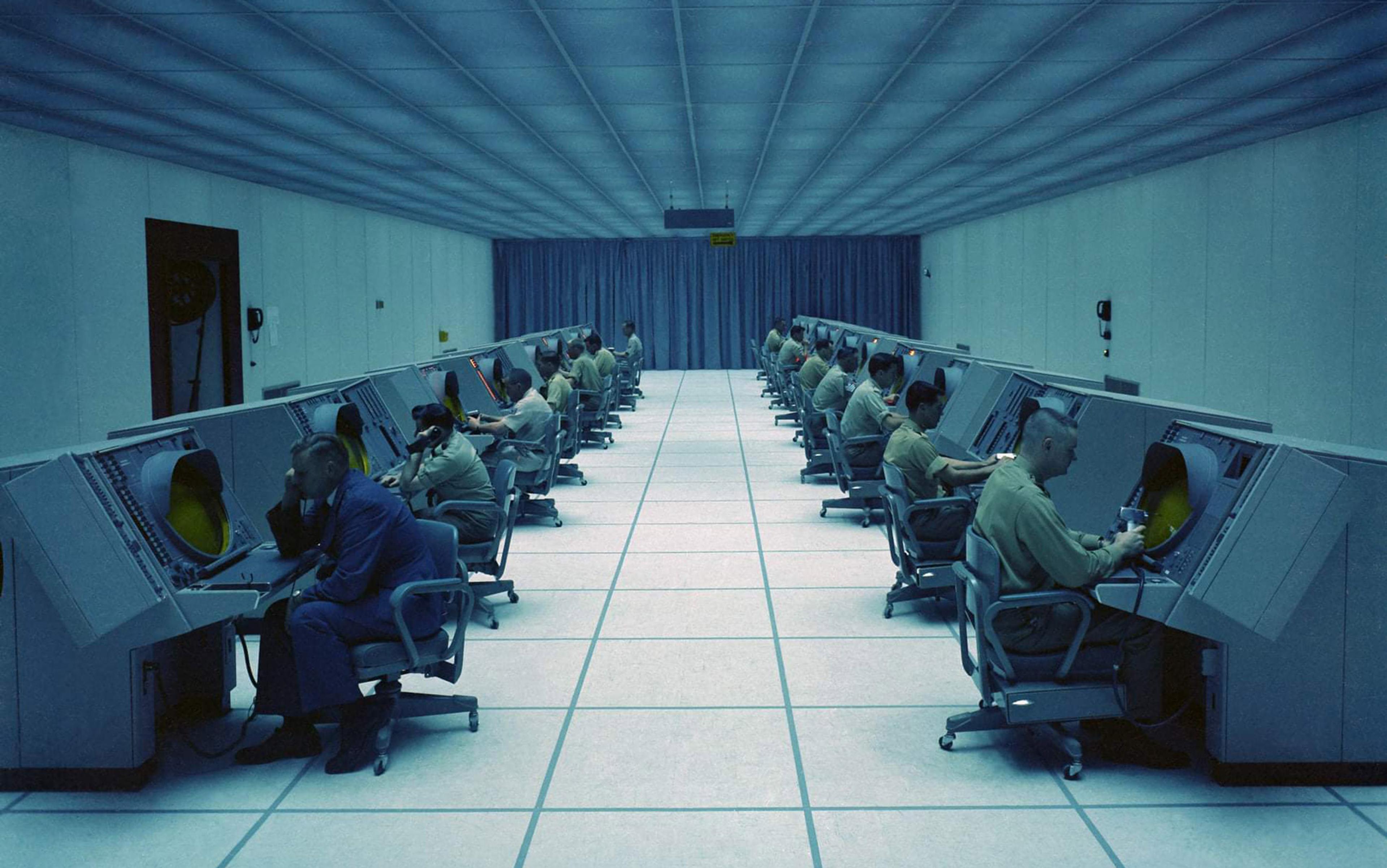

The tribe shaping Chomsky’s linguistics, I quickly discovered, was a community of computer scientists during the early years of the Cold War, employed to enhance electronic systems of command and control for nuclear war and other military operations. My book Decoding Chomsky (2016) was an attempt to explain the ever-changing intricacies of Chomskyan linguistics within this specific cultural and historical setting.

I took it for granted that the ideas people entertain are likely to be shaped by the kind of life they lead. In other words, I assumed that Chomsky’s linguistic theories must have been influenced by the fact that he developed them while working for the US military – an institution he openly despised.

Read the rest of this article at: Aeon

I spent the summer in Budapest learning Hungarian and eating raw fish. At first, I tried to eat the local food — goulash, schnitzel, langosh — and became severely bloated. Every time I ordered something simple it turned out to have lashings of paprika. Even fennel salad. Hungarians don’t appreciate menu substitutions, so I gave up and bought some smoked salmon and rice cakes from the grocery store. This quickly got depressing. Then I Googled sushi and found a restaurant on the Danube River.

It was on a quiet strip, down some stairs that led to a basement with small high windows where you could see people’s feet walking past. I ordered the tuna chirashi and a side of salmon sushi and my sensitive stomach was appeased. So I came back. Three nights in a row and then, surviving the embarrassment of walking in a fourth night, I just let myself go. I went there every night for a month.

Each time I ordered the same thing. When I entered, the staff recognized me and said something in Japanese that was warm and incantatory. No doubt they thought I was mad. Still, I was a loyal and well-behaved customer. The Danube is dirty, but eating raw fish by a body of water was reassuring. Sitting at basement level, watching the feet go by, I felt concealed. There was a child somewhere behind the kitchen door, presumably in the living space occupied by the owners, who was always crying. Normally I hate being in restaurants with noisy children, but somehow this didn’t bother me. I think I accepted the crying child as a toll for fresh sushi in a landlocked country.

Sometimes couples ate in the restaurant. They always ordered too much food and sat on their phones. Something about the bunkerlike space didn’t lend itself to conversation or to acknowledging that one was even conscious of being alive. Or maybe this was how couples ate together now. I hadn’t been in a couple for many years, so I didn’t know. One thing I appreciated about sushi was that there were no bones to choke on. Eating alone at a taverna in Greece the previous summer, I had consumed a bowl of fish soup with so many bones I’d felt like I was trying to detonate a bomb. The experience was both stressful and humiliating, especially with the Greek waitstaff all looking on. I suppose I wouldn’t have died alone there, or even died. But now I felt grateful to the Japanese, as if they had considered such things when inventing their cuisine.

Read the rest of this article at: The Cut