One evening in November, 2021, a group of men assembled at sundown on the terrace of the Ruckomechi Camp, a safari resort on the Zambezi River. Since arriving by private plane, they had gone out lion-spotting, boated down the river, and landed a giant tiger fish; now they were clinking gin-and-tonics. Hippos wallowed in the water below.

The party was led by Renat Heuberger, a forty-four-year-old Swiss entrepreneur with narrow eyes and a cropped copper beard. Heuberger was the chief executive of South Pole, the world’s largest carbon-offsetting firm, and he had come to Zimbabwe to fight off an urgent threat to his company.

A decade earlier, South Pole had signed a deal to sell carbon offsets from an effort to protect a vast swath of forest on the banks of Lake Kariba, upriver from the camp. The Kariba project, spanning an area ten times the size of New York City, was among the world’s first “avoided deforestation” programs; by deterring local people from chopping down trees, it promised to prevent the release of tens of millions of tons of greenhouse gas. Leading corporations, including Volkswagen, Gucci, Nestlé, Porsche, and Delta Air Lines, paid South Pole nearly a hundred million dollars for Kariba credits, allowing them to market goods or services as “carbon neutral.”

South Pole thus pioneered a model of carbon offsetting that has been counted among our best hopes for staving off climate catastrophe: a mechanism that diverts funds from polluters in wealthy countries to protect crucial ecosystems in the Global South. Heuberger, a kinetic, grandiloquent man, speaks expansively about his mission. “We’re here to save the climate,” he told me.

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

Staring into the mirror, on a Tuesday morning, you decide that your self needs all the help it can get. But where to turn? You were reading James Clear’s “Atomic Habits: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad Ones” and doing well until you spilled half a bottle of Knob Creek over the last sixty pages. Now you’ll never know how it ends. You tried listening to David Goggins’s “Can’t Hurt Me: Master Your Mind and Defy the Odds,” on Audible, in your car, but so thrilling was Goggins’s prose style that you stomped on the gas and rear-ended a Tesla. Do not despair, though. Succor is at hand. Roosting on Amazon’s best-seller list is “Build the Life You Want: The Art and Science of Getting Happier,” by Arthur C. Brooks and Oprah Winfrey (Portfolio).

At this point, your conscience rebels. By buying a book on Amazon, you tell yourself, you will be directly funding a new angora lining for Jeff Bezos’s monogrammed slippers in the master bedroom of his private yacht—not the main one but the backup vessel currently moored off Patmos. Quivering with righteousness, you close your laptop and stride to your nearest bookstore, only to bump into a dilemma: whereabouts in the store, exactly, can “Build the Life You Want” be found?

It is not an easy volume to place. You’d assume that it belongs on the self-help table. Yet the title suggests home improvement or even civil engineering, and so ardently does Brooks insist on the “four big happiness pillars”—family, friendship, work, and faith—that readers of a nervous disposition may choose to wear a hard hat. On the other hand, Brooks is a professor of management practice at Harvard Business School, so he would slot into the business section with ease. Given that, as he says, “the macronutrients of happiness are enjoyment, satisfaction, and purpose,” there’s an equally strong case for the cookery shelf. Or how about philosophy? Anyone who cites Marcus Aurelius, Thomas Aquinas, Kant, Mick Jagger, Epicurus, and Epictetus, as Brooks does, would be totally stoked to hang out in such lofty company. No one, of course, is loftier than his co-author, and, if your bookstore is furnished with an Oprah wing, that is where the book must be displayed.

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24962412/236808_Discogs_CVirginia.jpg)

If you are a devoted vinyl collector, an obsessive music fan, or — as is often the case — both, Discogs is very nearly a lifestyle. The site has become the internet’s foremost database of recorded music and one of the most extensive marketplaces available for physical music media, with every bit of it generated and offered by users. You can catalog your collection, look up information about even the most obscure artists, cross-check record store prices to see if your local shop has a markup, and purchase records, typically at something close to their “market rate.”

“Some people just buy records for the album art hanging on the wall,” says Doug Martin, who started selling on Discogs in 2020. But the Discogs users were different. “These were real fans listening to real music who cared about the format and the medium. That’s what attracted me in the beginning.”

The site has become a central part of the music internet, surviving through physical music media’s replacement by MP3s and then streaming — and rebounding as interest in vinyl, CDs, and tapes did throughout the 2010s. But sellers who use the platform say the site’s old tech has started to wear on them, and new fees and restrictions have made it harder to do business. Changes within the company are threatening to turn a bastion for vinyl fans, record stores, and anyone who cares about music into just another dysfunctional website — and dismantle a singular record of music history, even if just by pushing the sellers and users who have created that record away.

Read the rest of this article at: The Verge

Many people have put forth theories about why, exactly, the internet is bad. The arguments go something like this: Social platforms encourage cruelty, snap reactions, and the spreading of disinformation, and they allow for all of this to take place without accountability, instantaneously and at scale.

Clearly, we must upgrade our communication technology and habits to meet the demands of pluralistic democracies in a networked age. But we need not abandon the social web, or even avoid scalability, to do so. At MIT, where I am a professor and the director of the MIT Center for Constructive Communication, my colleagues and I have thought deeply about how to make the internet a better, more productive place. What I’ve come to learn is that new kinds of social networks can be designed for constructive communication—for listening, dialogue, deliberation, and mediation—and they can actually work.

To understand what we ought to build, you must first consider how social media went sideways. In the early days of Facebook and Twitter, we called them “social networks.” But when you look at how these sites are run now, their primary goal has not been social connection for some time. Once these platforms introduced advertising, their primary purpose shifted to keeping people engaged with content for as long as possible so they could be served as many ads as possible. Now powerful AI algorithms deliver personally tailored content and ads most likely to keep people consuming and clicking, leading to these platforms becoming highly addictive.

The unfortunate consequence of this model is that the best content for keeping eyes glued to screens is often the most emotionally provocative and polarizing content, regardless of quality or accuracy. Quieter voices get drowned out. Most people quickly come to understand that silence is safest and shift into a mode of passive consumption and emotion-driven sharing of content. Peer-to-peer communication is largely reduced to inconsequential chatter, given the risks of cancellation and trolling, which suppress meaningful conversation. Harms are most acute for youth, who feel social pressure to be on social media yet refrain from meaningful self-expression because of possible ostracism and bullying.

Read the rest of this article at: The Atlantic

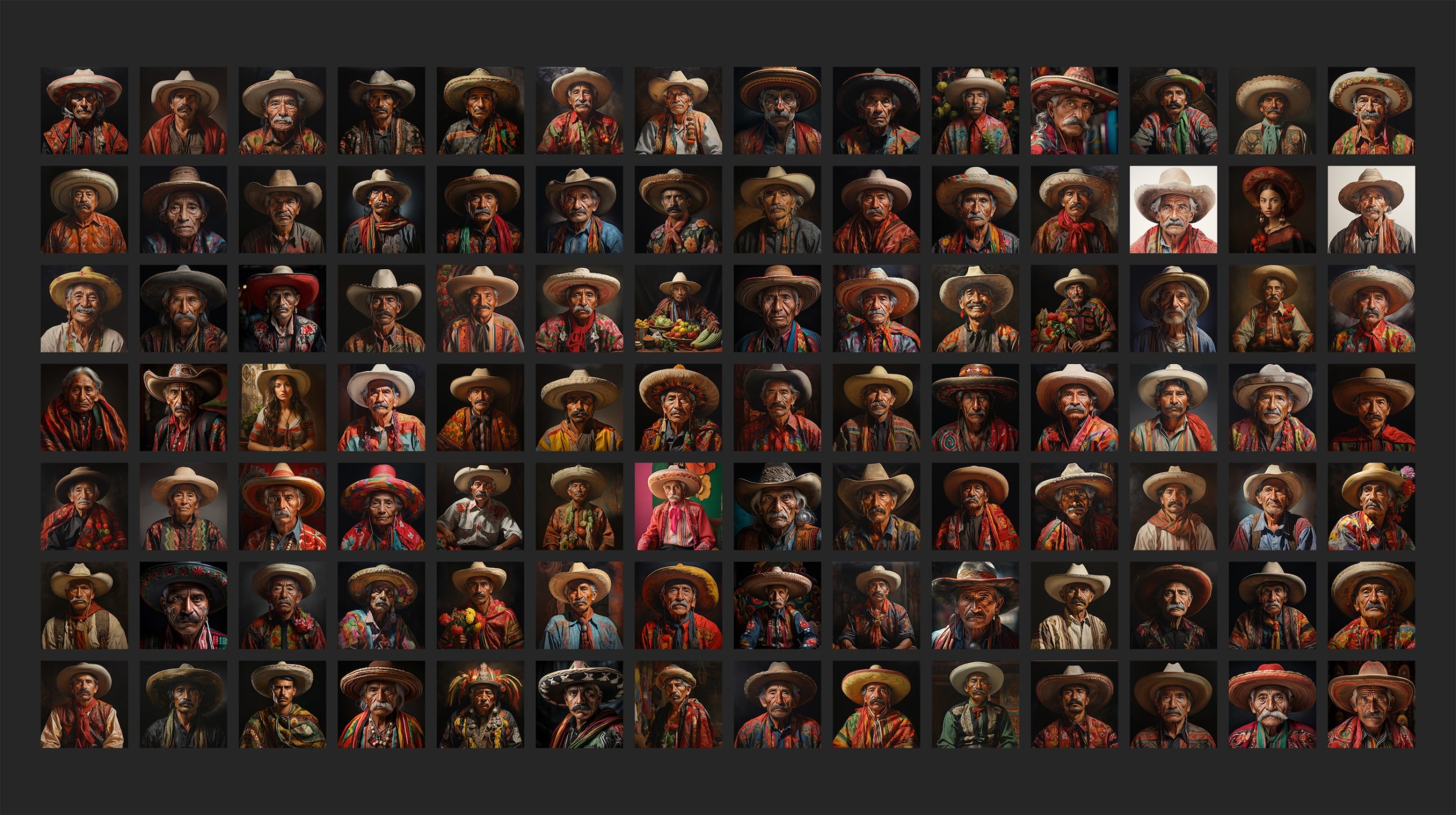

In July, BuzzFeed posted a list of 195 images of Barbie dolls produced using Midjourney, the popular artificial intelligence image generator. Each doll was supposed to represent a different country: Afghanistan Barbie, Albania Barbie, Algeria Barbie, and so on. The depictions were clearly flawed: Several of the Asian Barbies were light-skinned; Thailand Barbie, Singapore Barbie, and the Philippines Barbie all had blonde hair. Lebanon Barbie posed standing on rubble; Germany Barbie wore military-style clothing. South Sudan Barbie carried a gun.

The article — to which BuzzFeed added a disclaimer before taking it down entirely — offered an unintentionally striking example of the biases and stereotypes that proliferate in images produced by the recent wave of generative AI text-to-image systems, such as Midjourney, Dall-E, and Stable Diffusion.

Bias occurs in many algorithms and AI systems — from sexist and racist search results to facial recognition systems that perform worse on Black faces. Generative AI systems are no different. In an analysis of more than 5,000 AI images, Bloomberg found that images associated with higher-paying job titles featured people with lighter skin tones, and that results for most professional roles were male-dominated.

The article — to which BuzzFeed added a disclaimer before taking it down entirely — offered an unintentionally striking example of the biases and stereotypes that proliferate in images produced by the recent wave of generative AI text-to-image systems, such as Midjourney, Dall-E, and Stable Diffusion.

Bias occurs in many algorithms and AI systems — from sexist and racist search results to facial recognition systems that perform worse on Black faces. Generative AI systems are no different. In an analysis of more than 5,000 AI images, Bloomberg found that images associated with higher-paying job titles featured people with lighter skin tones, and that results for most professional roles were male-dominated.

Read the rest of this article at: Rest of the World