New York. A person can spend weeks in this port city without ever seeing the ocean. Skyscrapers. Central Park, with its sprawling lawns, trees, paths, vendors, a boathouse and restaurant: an urban refuge. Street performers at its edges. And people everywhere—in the park, on the streets. Tourists gawking, locals with places to be, a more urgent gait. At lunchtime, the restaurants are packed and efficient, set up for take-out and quick turnover. Fast-food joints: five minutes of eating, then dump your overflowing tray of coated paper, waxed or plastic cups, and Styrofoam shells into the garbage receptacle. More upscale spots: artisanal breads loaded with all the on-trend healthy ingredients, kombucha or green tea or decaf latte, double sugar, hold the fat. Still, the single-use cup, the single-use clamshell, the single-use cutlery, the single-use straw. Maybe eco-friendly-looking brown paper napkins. All tossed in the garbage or, covered with food scraps, into recycle bins. Which, then, magically disappear. Downtown Manhattan—you could eat off the streets. Where does all the garbage go?

Sure, there are dumpsters in back alleys, full to overflowing with garbage. Out of sight, out of mind. With an efficient waste management system, the city’s garbage literally disappears from view. It’s understandable that most people don’t concern themselves with it or wonder about where the garbage or their dirty recyclable materials are taken. By dropping their waste into the appropriate bin, they’ve done their duty. On to the next board meeting.

What if people were made aware that their dirty plastic waste is being packed onto container ships, bound for countries in Central America and Southeast Asia without the infrastructure or regulations to deal with it? Their plastic bottle of pure mineral water, now swirling in the tropical waters of the Andaman Sea, along with hundreds of tons of other plastic garbage dumped there—floating on the surface, suspended in the water column, filling the open mouths of manta rays. Or lying on the ocean floor, smothering coral reefs.

Read the rest of this article at: The Walrus

I was trying to reach Gary Kruglitz, the proprietor of Royal Palace Pools and Spas. Gary cuts a certain figure. Just a hair over 6 feet tall, wears a mustache, square wire-rimmed bifocal glasses, thin short-sleeved dress shirts through which it is occasionally possible to glimpse just the hint of nipple when the lighting is right. He has an unusually high voice for a man his size, as if a Muppet crawled down his throat one night and couldn’t get out again. I wouldn’t say Gary is perplexed by this modern world we find ourselves living in as much as he might not be aware it exists. Sometimes when you talk to him, he’ll look up from his papers, turn in your direction, and blink, like a bird that has heard something in the underbrush.

Gary — I changed his name so I could be as honest about him and his nipples as possible — spends his days working out of his pool warehouse, in an office covered desk-to-credenza in product manuals and spa brochures and invoices produced in gold-, pink-, and white-triplicate. A man trapped in the amber of another era, the type of guy who answers his phone yellllow and says bye now when he hangs up. But at this moment, Gary was not answering his phone at all. And I was desperate to reach him, because my wife and I had paid him a deposit of $31,500 to build us a pool, and he had apparently disappeared off the face of the earth.

“I’m sorry, Gary is not available right now,” said Cheryl when I phoned that morning.

As best I could tell, there were three women who worked at Royal Palace Pools. Cheryl, Cheryl, and Sheryl. (Could be wrong on that.) The Cheryls didn’t have offices. They stood point at the front of the store, behind the glass cases where the chlorine tablets and pool thermometers are displayed. There was a rumor that one of the Cheryls — Sheryl — was Gary’s wife, but I couldn’t imagine Gary making love, or having breakfast each morning with someone in his home. I believed the likelier scenario was that each night when the Cheryls went home, Gary climbed into an empty Jacuzzi shell with a bag of Funyuns and a worry-worn pad of invoices that served as his transitional object, pulled the thermal cover over himself, and waited in the dark with his eyes open until he could go back to the office. Regardless, if you wanted to get in touch with him, there was going to be at least one Cheryl between you and Gary.

“Do you know where he is?” I said. “This is urgent.”

“Um. And who is this?” said Cheryl.

I gave her my name and her tone changed a bit.

“I see,” she said tightly. “Well, I’ll tell him that you called. Again.”

“Please do,” I said, trying to sound both grateful and angry. Then I hung up.

Read the rest of this article at: Insider

Robert Konashewych was a young police officer with expensive tastes, two girlfriends and a mountain of debt. Heinz Sommerfeld was recently deceased with a large unclaimed estate. Problem, meet solution

As teenagers, Robert Konashewych and Candice Dixon made a pact straight out of a rom-com. Growing up in Oakville, he was the handsome older guy from school she’d see behind the cash at Loblaws when her mom dragged her out grocery shopping. She was the cute girl one grade below he’d call for relationship advice. They jokingly promised that, if they were both single at 35, they’d get together. When they ran into each other in 2011 at the Brant House on King West, the dance floor seething dry ice, Konashewych mentioned the pact. By then, they were in their late 20s, and it seemed less like a joke and more like a possibility. “Married, right?” he asked her. She shook her head no. “So,” he said, “I still have a chance?” Dixon was statuesque, with long, gleaming brown hair and arched eyebrows. Mike Tyson once told her she had a body built by Ferrari. Konashewych was tall too, and muscular, with short hair and the shadow of a beard. The pair made their way outside, sat on a bench and talked into the night.

Read the rest of this article at: Toronto Life

Daniel Aritonang graduated from high school in May, 2018, hoping to find a job. Short and lithe, he lived in the coastal village of Batu Lungun, Indonesia, where his father owned an auto shop. Aritonang spent his free time rebuilding engines in the shop, occasionally sneaking away to drag-race his blue Yamaha motorcycle on the village’s back roads. He had worked hard in school but was a bit of a class clown, always pranking the girls. “He was full of laughter and smiles,” his high-school math teacher, Leni Apriyunita, said. His mother brought homemade bread to his teachers’ houses, trying to help him get good grades and secure work; his father’s shop was failing, and the family needed money. But, when Aritonang finished high school, youth unemployment was above sixteen per cent. He considered joining the police academy, and applied for positions at nearby plastics and textile factories, but never got an offer, disappointing his parents. He wrote on Instagram, “I know I failed, but I keep trying to make them happy.” His childhood friend Hengki Anhar was also scrambling to find work. “They asked for my skills,” he said recently, of potential employers. “But, to be honest, I don’t have any.”

At the time, many villagers who had taken jobs as deckhands on foreign fishing ships were returning with enough money to buy motorcycles and houses. Anhar suggested that he and Aritonang go to sea, too, and Aritonang agreed, saying, “As long as we’re together.” He intended to use the money to fix up his parents’ house or maybe to start a business. Firmandes Nugraha, another friend, worried that Aritonang was not cut out for hard labor. “We took a running test, and he was too easily exhausted,” he said. But Aritonang wouldn’t be dissuaded. A year later, in July, he and Anhar travelled to the port city of Tegal, and applied for work through a manning agency called PT Bahtera Agung Samudra. (The agency seems not to have a license to operate, according to government records, and did not respond to requests for comment.) They handed over their passports, copies of their birth certificates, and bank documents. At eighteen, Aritonang was still young enough that the agency required him to provide a letter of parental consent. He posted a picture of himself and other recruits, writing, “Just a bunch of common folk who hope for a successful and bright future.”

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

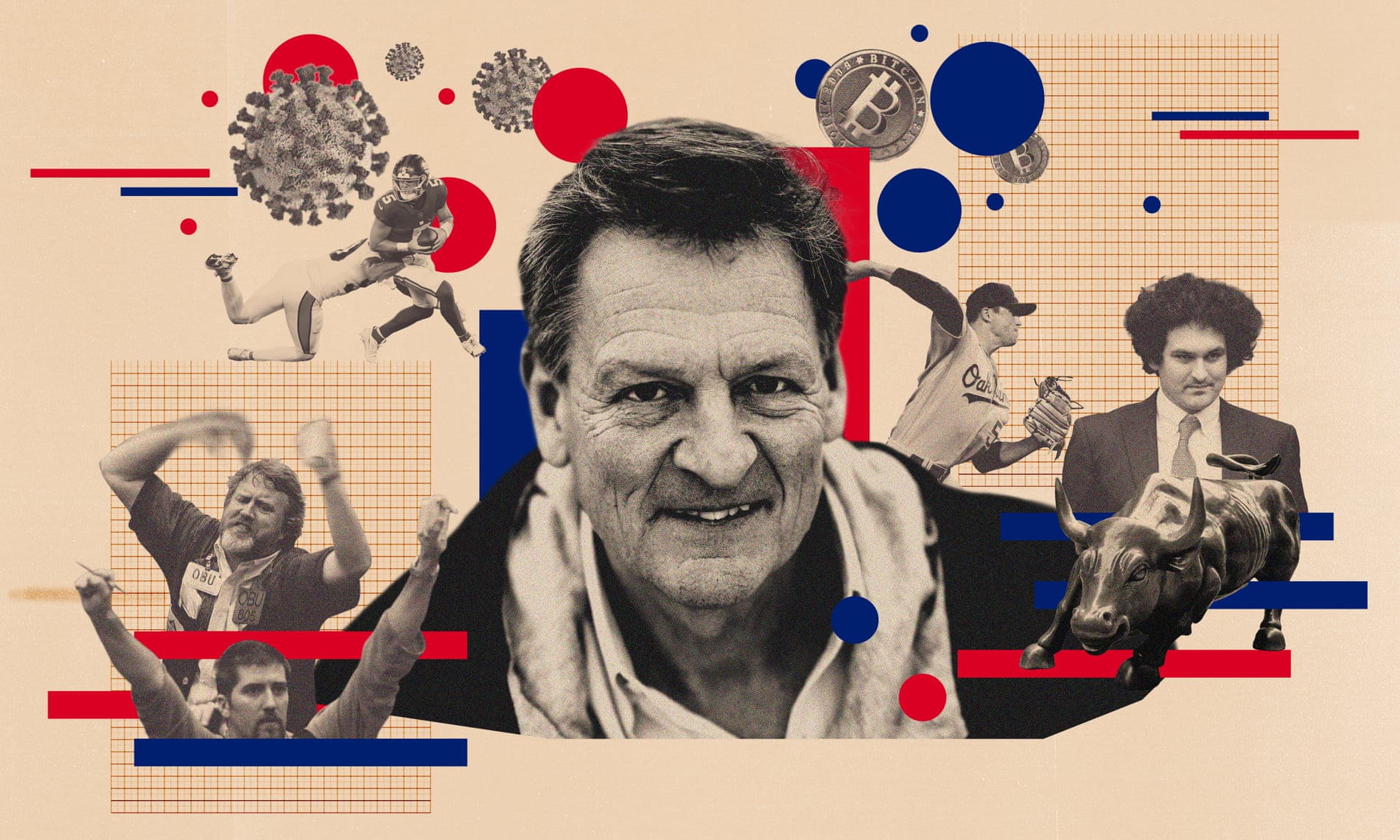

Right around the time the gales of the financial crisis were tearing up Wall Street in 2009, Meredith Whitney started her own financial research firm. Whitney, a stock market analyst, had predicted the crash of the previous year, and among the journalists who had sought her out had been Michael Lewis. When her new Manhattan office opened and she threw “a party for all the muckety-mucks”, she invited Lewis. He had just published a magazine article calling Wall Street’s titans greedy and stupid, so thrusting him into a gathering of those selfsame titans was like taking a Broadway heckler into the play’s dressing rooms. “But all these former heads of investment banks, all these current bankers – they ran, not walked, to the office, just to meet him,” Whitney said. “One hedge fund manager walked in with 15 copies of Lewis’s books. Michael signed them all.”

Lewis enjoys a rare kind of celebrity among the moneyed men and women of the US. They believe he gets them, that he is the Hemingway of their bullring. He used to be one of them, after all: a Salomon Brothers bond salesman in the late 1980s, and therefore part of the extravagant avarice that defined Wall Street in that decade. Then he quit to write a memoir about it, Liar’s Poker. It was the first in a series of blockbusters about the thin top slice of American society: the one in which Whitney and her muckety-mucks reside, alongside other mavens, savants and powerbrokers. They drive its commerce and politics, its sports and culture – and Lewis is their bard. He’s the kind of writer Vanity Fair will call upon to interview Barack Obama one day, Arnold Schwarzenegger the next. When a rumour surfaced that Vanity Fair used to pay Lewis $10 a word – while most journalists otherwise languish in the 50-cent range – it almost didn’t matter if it was true. (It was, it turned out.) The rumour merely confirmed what everyone knew: Lewis is the most prestigious narrator of American life.

Read the rest of this article at: The Guardian