The Web site Stack Overflow was created in 2008 as a place for programmers to answer one another’s questions. At the time, the Web was thin on high-quality technical information; if you got stuck while coding and needed a hand, your best bet was old, scattered forum threads that often led nowhere. Jeff Atwood and Joel Spolsky, a pair of prominent software developers, sought to solve this problem by turning programming Q. & A. into a kind of multiplayer game. On Stack Overflow—the name refers to a common way that programs crash—people could earn points for posting popular questions and leaving helpful answers. Points earned badges and special privileges; users would be motivated by a mix of altruism and glory.

Within three years of its founding, Stack Overflow had become indispensable to working programmers, who consulted it daily. Pages from Stack Overflow dominated programming search results; the site had more than sixteen million unique visitors a month out of an estimated nine million programmers worldwide. Almost ninety per cent of them arrived through Google. The same story was playing out across the Web: this was the era of “Web 2.0,” and sites that could extract knowledge from people’s heads and organize it for others were thriving. Yelp, Reddit, Flickr, Goodreads, Tumblr, and Stack Overflow all launched within a few years of one another, during a period when Google was experiencing its own extraordinary growth. Web 2.0 and Google fuelled each other: by indexing these crowdsourced knowledge projects, Google could get its arms around vast, dense repositories of high-quality information for free, and those same sites could acquire users and contributors through Google. The search company’s rapacious pursuit of other people’s data was excused by the fact that it drove users toward the content it harvested. In those days, Google even measured its success partly by how quickly users left its search pages: a short stay meant that a user had found what they were looking for.

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

Late last month, after a year-plus wait, OpenAI quietly released the latest version of its image-generating AI program, DALL-E 3. The announcement was filled with stunning demos—including a minute-long video demonstrating how the technology could, given only a few chat prompts, create and merchandise a character for a children’s story. But perhaps the widest-reaching and most consequential update came in two sentences slipped in at the end: “DALL-E 3 is designed to decline requests that ask for an image in the style of a living artist. Creators can now also opt their images out from training of our future image generation models.”

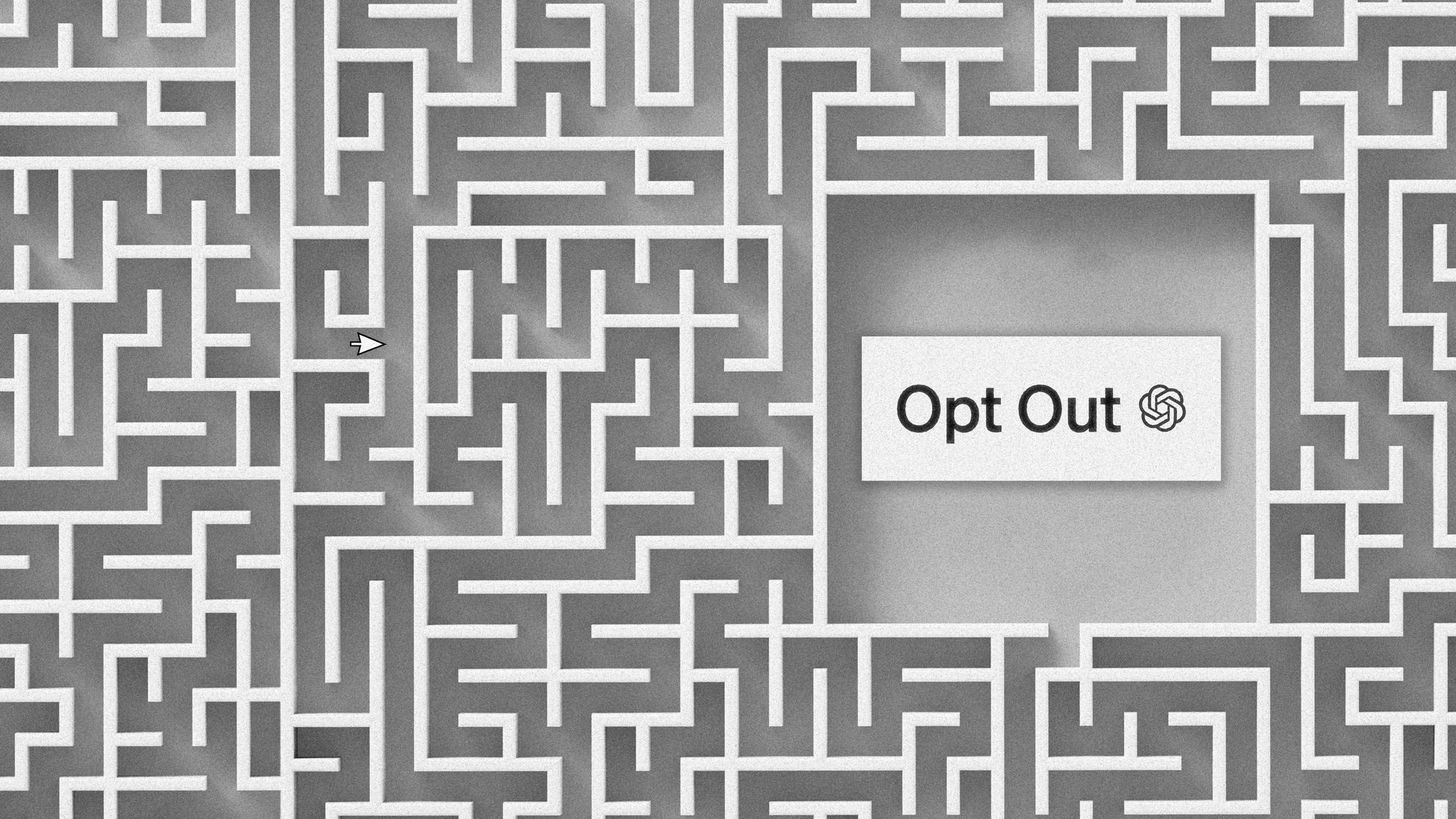

The language is a tacit response to hundreds of pages of litigation and countless articles accusing tech firms of stealing artists’ work to train their AI software, and provides a window into the next stage of the battle between creators and AI companies. The second sentence, in particular, cuts to the core of debates over whether tech giants like OpenAI, Google, and Meta should be allowed to use human-made work to train AI models without the creator’s permission—models that, artists say, are stealing their ideas and work opportunities.

OpenAI is claiming to offer artists a way to prevent, or “opt out” of, their work being included among the millions of photos, paintings, and other images that AI programs like DALL-E 3 train on to eventually generate images of their own. But opting out is an onerous process, and may be too complex to meaningfully implement or enforce. The ability to withdraw one’s work might also be coming too late: Current AI models have already digested a massive amount of work, and even if a piece of art is kept away from future programs, it’s possible that current models will pass the data they’ve extracted from those images on to their successors. If opting out affords artists any protection, it might extend only to what they create from here on out; the work published online in all the time before 2023 could already be claimed by the machines.

Read the rest of this article at: The Atlantic

At the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust centre in Slimbridge, Gloucestershire, children zigzagged between the duckponds like bees performing a cryptic private dance. The sound of children screaming makes my hands judder, in half-remembered horror. But today I could bear it, because there were geese to feed; they ran after me, pistoning seed out of my hand and leaving crescents of mud behind. As we left the feeding area, birdwatching hides rose up from the path: dark and shady, with silence inside and long windows giving out on to the marshy flatlands around the Severn Estuary. This was more like it.

Very quietly, we unhooked the wooden window clasps and let the pane down. My friend settled in with his binoculars, while I, chin-on-arms, watched the flat landscape – the low, ironed green, sprinkled with buttercups; the patches of water like gleaming fallen coins. We’d come in summer: a bad time for wetland wildfowl, my friend told me. In wintertime, godwits and dunlin and grey plovers come in from northern Europe and Russia to nibble on Britain’s mudflats. But when the weather gets warmer, many of these nice solid wading birds go back to the Arctic Circle, and leave Britain’s flat landscapes to themselves. That was OK with me. I was really here for the bare, stretched horizons of the wetlands. The flat places with nothing much to look at.

Read the rest of this article at: aeon

In 2014, the National Rail Passenger Corporation, best known as Amtrak, pulled off one of the epic marketing coups of U.S. railroad history—granted, there haven’t been many of late—when they announced the Amtrak Residency for Writers, where they would send 24 writers on cross-country trips, meals and beds gratis, to write the Great American Novel. The announcement of this perfect marriage of two beloved dinosaurs—trains and publishing!—set Twitter aflame, like hearing Panasonic and Oldsmobile had teamed up to launch a new line of gas-powered fax machines.

Around the same time, evil scientist Elon Musk announced his plan for the Hyperloop, a high-speed transport system where humans would be jammed into cans like Vienna sausages and shipped across the nation via pneumatic mail; meanwhile, Astronerd Jeff Bezos and his Amazonian Savings Monster continued to strip-mine the foundations of the literary ecosystem. So this little PR stunt by Amtrak, the desktop PC of the global travel industry, a national embarrassment to hide from your European friends, smelled of quiet revolution. Together, trains and writers would lay siege to the behemoth of late-stage capitalism.

There’s a silent movie by Ernst Lubitsch from 1919 called The Doll, in which a woman has to pretend she’s a doll to her fiancé while also convincing him that she’s convincing a wedding party that she’s a real person (which she is). This strikes me as a more sophisticated approach to the gender bind than anything in Greta Gerwig’s Barbie, in which the doll-as-doll (Margot Robbie), now in the real world, goes up to a construction crew (the working class) to announce that she doesn’t have a vagina. That just seems schizophrenic, or hysterical in the old-school sense, instead of funny.

I guess it’s a joke about white privilege, or blonde privilege, but the construction workers don’t really get vulgar with Barbie, like they might in the real real world. In fact, freed from her Barbieland enclave, she strides through Los Angeles unharassed. Everyone is nice to her, including the owner of a store where she’s shoplifting, and then the police, who let her go. The only meanie is a teenage girl who calls Barbie a fascist, also a joke because we already know Barbie is totally, perfectly egalitarian as a citizen of Barbieland, except with Ken (Ryan Gosling), who is beneath her as a member of a caste born to be her accessory and nothing more, and who is also homeless. Supposedly things are the opposite in the real world, but we never quite see that. We just have to take it for granted that there, in reality, the Barbies are the accessories for the Kens, even though there are women doctors who stop Ken from performing surgery just because he wants to.

Read the rest of this article at: Longreads

A T 5:44 P.M. ON FEB. 23, 2022, my phone lit up with a WhatsApp message from a stranger. “Hello Sean Williams,” he wrote. “I have something for you.”

Seconds later, the stranger sent a link to a Spectrum 1 News interview with a retired LAPD cop and writer named Cheryl Dorsey. Dorsey had penned a biography titled The CONfidence Chronicles, about a “Black criminal genius” named Maverick Miles Nehemiah, who’d swindled the U.S. government out of $20 million via counterfeit savings bonds in the Eighties. Nehemiah hadn’t cashed the bonds himself, Dorsey told the reporter in the interview. Rather, he’d enlisted three women and three men — the “All-American Team,” as he called them — whose skin color wouldn’t raise the eyebrows of racist bank tellers.

Nehemiah had served five years in prison for the scam, Dorsey explained in the clip, and he’d since built a business refurbishing vintage Porsche 928s out of a downtown L.A. hangar. Now, Dorsey explained, Nehemiah was ready to share his tale with the world. “It’s a story of redemption,” she told the reporter.

Seven minutes later, the stranger sent me a third message. “I’ve been very careful in selecting the ‘right’ journalist with this one-of-a-kind true-crime story Sean,” it read. “As I remain, in hope and trust, Maverick Miles Nehemiah.”

Dorsey had already been a go-to police expert for cable-news shows before writing The CONfidence Chronicles, and she had plugged the book via appearances on MSNBC, CNN, and others. But she had failed to secure a contract, and sales of the self-published result had flagged. Maverick wanted a major magazine to cover his story, too.

“I’d be lying,” I wrote him back, “if I said I weren’t interested.”

The following day, Maverick emailed me a PDF copy of Dorsey’s book. The CONfidence Chronicles had all the ingredients of a true-crime classic — even if, on first glance, many of its details read jarringly like fiction. In it, Maverick, the Texas-raised adopted son of a Pueblo Indian pianist mother and Black airman father, channeled increasing disillusionment with America’s history of racism, and failed shots at pro football, into a daredevil scheme to defraud the government — perfecting counterfeit U.S. Treasury bonds, before dispatching his hand-selected All-American Team to cash them, or “walk the paper” as he called it, in banks up and down the country. He decked out his counterfeit runners with flashy clothes and went on trips to the Caribbean. But his own motivations ran deeper. “Maverick believed that this country had then and continues to this day — an agenda to ‘keep Black people down,’” Dorsey wrote. “Maverick went after the government’s money.” He’d aimed to walk $50 million of the bonds. But one of the so-called All-American Team, a hard-drinking Midwesterner he called “Delilah,” had, “because of her greed and betrayal,” wrote Dorsey, hit banks on her own, gotten arrested, and snitched.

Read the rest of this article at: Rolling Stone