The story of how a guy named Mickey Barreto came to own, at least on paper, the New Yorker hotel is a weird one. It started in June 2018, when Barreto first booked a night at the Art Deco landmark for $149. He had plans to stay a while: Using an obscure clause in the city’s rent-stabilization law, Barreto requested a six-month lease to live at the hotel. The gambit worked. Even as the owner of the hotel, which happens to be the Unification Church despite the fact that it operates as a Wyndham, tried to boot him, the judge ordered them to let him back in.

Around the same time he requested the lease, and despite the fact that he did not own the New Yorker, Barreto filed a deed transferring ownership of the hotel from himself to something called Mickey Barreto Missions. Why did Barreto believe he owned the building? As he told a judge in 2019, the “building was never subdivided. It’s all one lot. It’s all one parcel.” Which meant, at least to him, that because he had a legal claim to room 2565, he had a legal claim to the whole thing: “What affects that part of the building called 2565, whatever happens in there, happens to the whole lot, the whole parcel.” He then went around presenting himself as the owner, attempting to collect rent from the building’s street-level businesses and at one point calling the Fire Department to have the building evacuated and, per court documents, identifying “himself as the owner of the subject property.” In the end, the judge found Barreto’s deed, which was extremely fraudulent, to be extremely fraudulent.

But Barreto wasn’t done! The Commercial Observer reports that Barreto made another play at ownership this month, with a 2021 deed transfer from Mickey Barreto Missions to … Mickey Barreto Missions. (Barreto only signed the document earlier this month, and the Department of Finance made it public shortly after.) All of which raises some important questions: Why is it so easy to fake-own a building in New York City? And what is this rent-stabilization law Barreto took advantage of? To help make sense of everything, and potentially try it myself, I reached out to David Reiss, a professor at Brooklyn Law School, who explained everything.q

Read the rest of this article at: Curbed

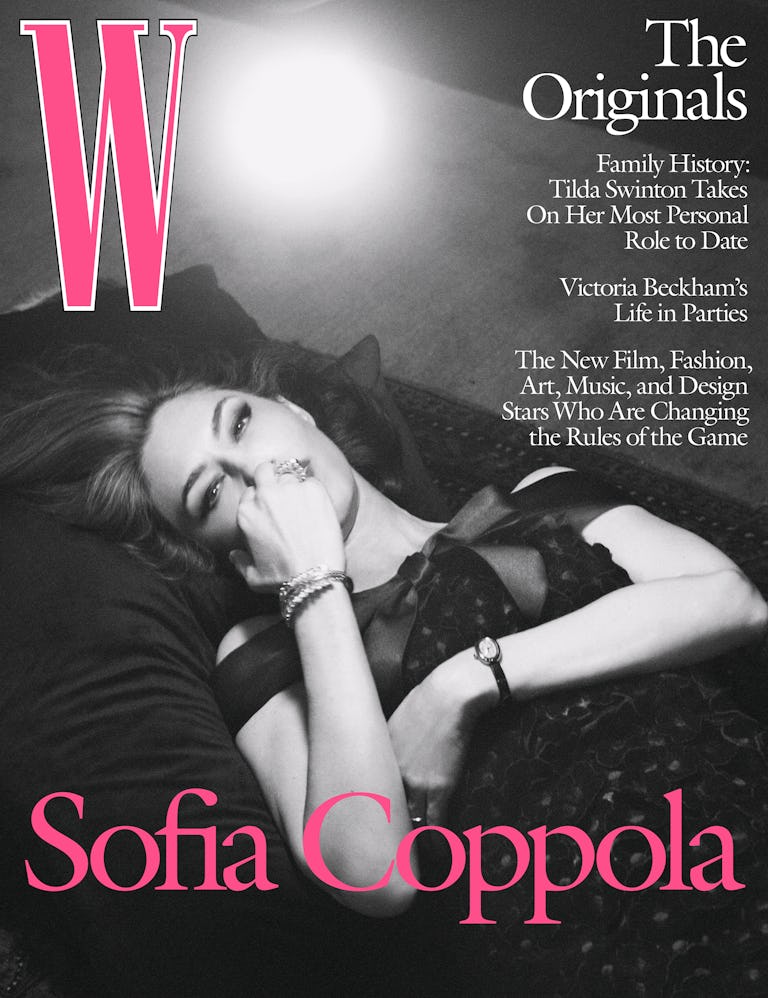

When Sofia Coppola was growing up, her father, Francis Ford Coppola, would take the entire family from their home in Napa Valley, California, to the location of whatever movie he was directing. Sofia was born in New York City, and was the baby in the baptism scene in The Godfather; she attended kindergarten in the Philippines during Apocalypse Now; she went to grade school in Tulsa, Oklahoma, while The Outsiders and Rumble Fish were shot back-to-back. “I was always around the set,” Coppola told me on a humid summer day in Manhattan. We were having lunch at Sant Ambroeus on the Upper East Side, and while most of the people in the crowded restaurant appeared wilted from the heat, Coppola, who was wearing a crisp white short-sleeve shirt tucked at the waist into loose, beautifully tailored dark navy pants, looked, as usual, perfect.

“I had a small part in Rumble Fish,” Coppola recalled, taking a sip of water. “I played the bratty younger sister. My father cast me because I was around, and he loved to include his family in his work. Rob Lowe was in The Outsiders, and he and his girlfriend at the time, Melissa Gilbert, took me out for ice cream to Rumpelmayer’s when we were back in New York.” Coppola smiled at the memory. “I was like an Army brat—always going to different schools in different towns. All that moving around has helped me: I’m good at being in new situations all the time. And it’s one of the reasons why I can relate to Priscilla. She actually was an Army brat.”

Priscilla is Priscilla Presley, the subject of Coppola’s new film, Priscilla, out in theaters on November 3. Based on Presley’s memoir, Elvis and Me, the film follows the titular character, who is played by Cailee Spaeny, from when she first encountered Elvis, on a military base in Germany, to when she ended their marriage, 14 years later. Like almost all of Coppola’s eight feature films—but especially The Virgin Suicides, Lost in Translation, and Marie Antoinette—it is a study in how girls grow up and evolve due to time and circumstance. Priscilla’s life was utterly transformed by her romance with Elvis.

Read the rest of this article at: W Magazine

Right now, many forms of knowledge production seem to be facing their end. The crisis of the humanities has reached a tipping point of financial and popular disinvestment, while technological advances such as new artificial intelligence programmes may outstrip human ingenuity. As news outlets disappear, extreme political movements question the concept of objectivity and the scientific process. Many of our systems for producing and certifying knowledge have ended or are ending.

We want to offer a new perspective by arguing that it is salutary – or even desirable – for knowledge projects to confront their ends. With humanities scholars, social scientists and natural scientists all forced to defend their work, from accusations of the ‘hoax’ of climate change to assumptions of the ‘uselessness’ of a humanities degree, knowledge producers within and without academia are challenged to articulate why they do what they do and, we suggest, when they might be done. The prospect of an artificially or externally imposed end can help clarify both the purpose and endpoint of our scholarship.

Read the rest of this article at: aeon

Olivia Hussey was 15 years old when Franco Zeffirelli cast her in his adaptation of Romeo and Juliet. She had been a working stage actor for a few years but was unknown in the world of film and had no agent or manager. Her parents had split up when she was 1, and she hadn’t seen her father, an Argentine singer, since she was 7; her mother, a British secretary who worked three jobs, wasn’t around on set. To make the film, Olivia, along with her co-star, Leonard Whiting, moved in with the director in his villa outside Rome. Hussey was in awe of Zeffirelli. “When he comes into the room and speaks, no one else says anything,” she told a journalist at the time. “No one else can compete with anything he says, his ideas are so brilliant.” Sometimes she called him “Daddy.”

If he was a father figure, he wasn’t a very nurturing one. His focus on her body was relentless. Before the shoot began, she was ordered to go to a doctor who prescribed her diet pills that made her ill. By the time the cameras were rolling, Olivia weighed 100 pounds and wasn’t allowed to gain any weight. When she told Zeffirelli she was self-conscious about her chest and wasn’t sure about wearing a low-cut dress, he gave her the nickname “Boobs O’Mina,” which he would shout into a megaphone whenever he wanted her on set. She later reasoned he had humiliated her in order to break down her defenses. “Clever man,” she wrote in her memoir. “By constantly calling attention to my body, he had drained away my embarrassment.”

Zeffirelli waited until nearly the end of production to shoot the film’s most controversial scene. In a departure from Shakespeare’s text, he moved the young lovers’ postcoital scene from Juliet’s balcony to her bedroom. He shot the couple naked in bed together, covered only by a sheet and the angle of the camera. Olivia did not realize she would be fully undressed until that morning, when the makeup man arrived and announced he was there to make her up “head to toe.” Panicking, she ran to Zeffirelli, who promised her the audience would see only “a hint — a bare back, a shoulder.” For most of the shoot, she lay in bed holding the sheet over her chest, but Zeffirelli had placed her nightgown out of reach so that her nipples were briefly exposed when she rose to get it. She didn’t realize this moment made the final cut until she saw the film for the first time at its royal premiere in London, where she sat behind Prince Philip, Prince Charles, and the queen.

Read the rest of this article at: Vulture

The fudge sold at Copper Kettle was so creamy, so sweet, so beyond compare, that many candy shops on the Ocean City boardwalk didn’t even sell fudge, because there was no point. During summer vacations to the Jersey Shore in the 1970s, my father would take my brother and me as a treat, when we behaved. A pretty girl in a pinafore would greet us outside with a tray of free shavings. We’d load up on them until her smile strained, then proceed inside. Once we popped actual cubes of the magic stuff into our tiny mouths, we were as high as kids are allowed to be.

For decades, Copper Kettle lived in my head as a kind of childhood memory-scape: the salt air coming off the ocean, the shiny vats of molten fudge, the too much sugar all at once. Then, during the pandemic, my family decided to return to the Jersey Shore for my mother’s birthday, so everyone could gather outside. I told my brother we should make our way back to Copper Kettle, and he informed me that it had long since gone out of business. He had some more information too: about what had become of Harry Anglemyer, the man behind the fudge.

In the early 1960s, Harry had a string of Copper Kettle Fudge shops up and down the Shore. So revered were his stores that Harry was known far and wide as the Fudge King. He was even in talks to build a fudge factory—something that would’ve taken his Willy Wonka–ness to the next level—when he was savagely beaten to death on Labor Day 1964. His body was stuffed under the dashboard of his Lincoln Continental, parked at an after-hours nightclub called the Dunes. The case was never solved.

I spent the next two years sorting through a trove of whispers and accusations around the murder. At first I was just curious, but the more I learned about Harry—a figure beloved by friends and strangers alike—the more intent I was to identify his killer.

I scoured blogs, Facebook groups, newspaper archives, and thinly veiled fictional accounts of the crime. As one local put it, over the years a veritable “Jersey Shore QAnon” had blossomed around the murder, raising questions of culture, class, sexuality, and hierarches of power. I discovered a plausible myth, a trove of red herrings, and, finally, what appeared to be the truth.

Almost six decades on, I wasn’t sure anyone wanted to hear it. When I visited Ocean City while reporting this story, a shop owner I engaged about Harry Anglemyer lowered her voice and said, “You know he was murdered, don’t you?”

I admitted that I did.

She responded, by way of warning: “You sneeze in this town and everyone hears it.”

Read the rest of this article at: Atavist Magazine