My childhood Barbies were always in trouble. I was constantly giving them diagnoses of rare diseases, performing risky surgeries to cure them, or else kidnapping them—jamming them into the deepest reaches of my closet, without plastic food or plastic water, so they could be saved again, returned to their plastic doll-cakes and their slightly-too-small wooden home. (My mother had drawn her lines in the sand; we had no Dreamhouse.) My abusive behavior was nothing special. Most girls I know liked to mess their Barbies up; and when it comes to child’s play, crisis is hardly unusual. It’s a way to make sense of the thrills and terrors of autonomy, the problem of other people’s desires, the brute force of parental disapproval. But there was something about Barbie that especially demanded crisis: her perfection. That’s why Barbie needed to have a special kind of surgery; why she was dying; why she was in danger. She was too flawless, something had to be wrong. I treated Barbie the way a mother with Munchausen syndrome by proxy might treat her child: I wanted to heal her, but I also needed her sick. I wanted to become Barbie, and I wanted to destroy her. I wanted her perfection, but I also wanted to punish her for being more perfect than I’d ever be.

It’s not that I literally wanted to become her, of course—to wake up with a pair of hard plastic tits, coarse blond hair, waxy holes in my feet betraying the robotic fingerprint of my factory birthplace—but some part of me was already chasing the false gods she spoke for: beauty as a kind of spiritual guarantor, writing blank checks for my destiny; the self-effacing ease afforded by wealth and whiteness; selfhood as triumphant brand consistency, the erasure of opacity and self-destructive tendency. I craved all of these—still do, sometimes—even as my own awareness of their impossibility makes me want to destroy their false prophet: Barbie as snake-oil saleswoman hawking the existential and plasticine wares of her impossible femininity, one Pepto-Bismol-pink pet shop at a time.

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

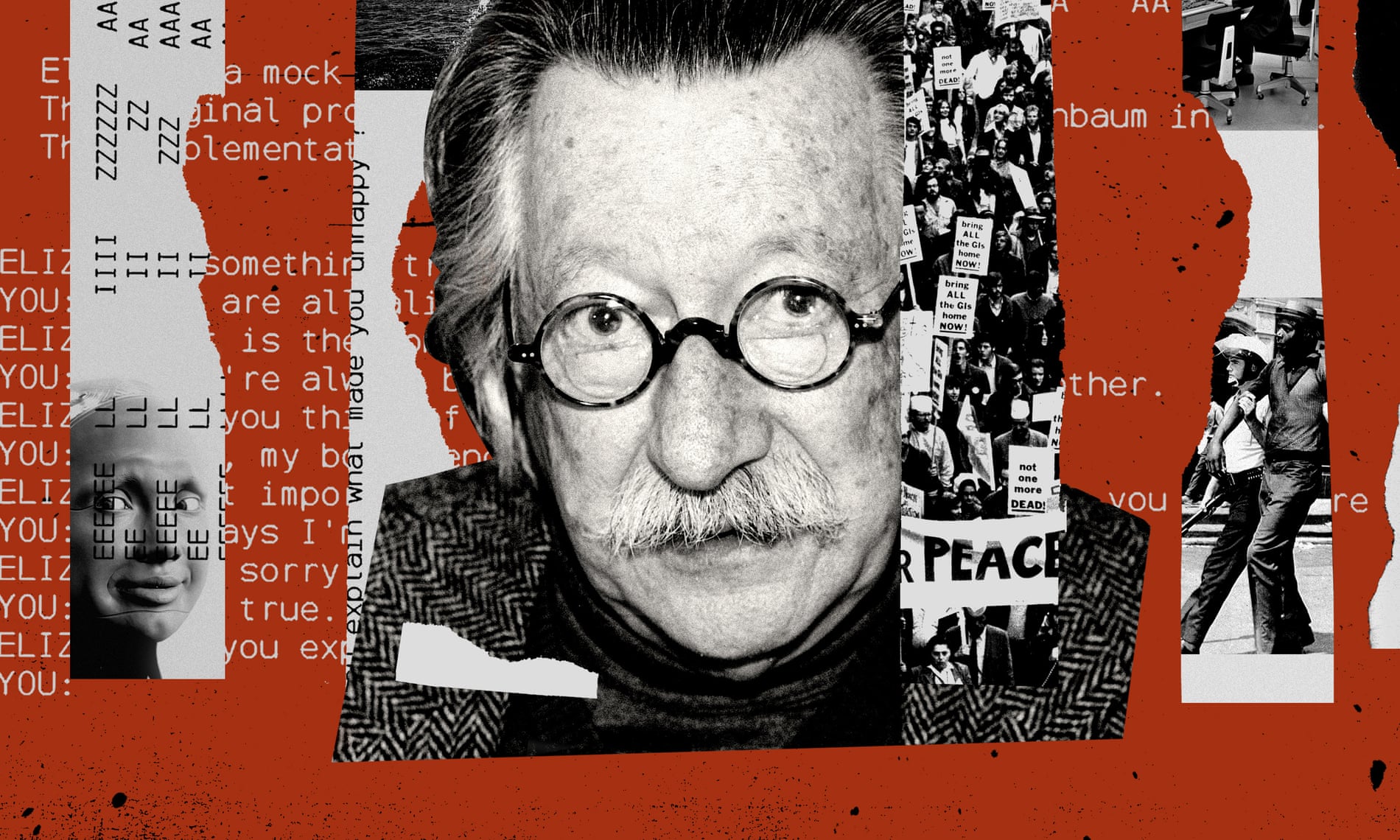

In 1966, an MIT professor named Joseph Weizenbaum created the first chatbot. He cast it in the role of a psychotherapist. A user would type a message on an electric typewriter connected to a mainframe. After a moment, the “psychotherapist” would reply.

User: Men are all alike.

Chatbot: IN WHAT WAY

User: They’re always bugging us about something or other.

Chatbot: CAN YOU THINK OF A SPECIFIC EXAMPLE

User: Well, my boyfriend made me come here.

Chatbot: YOUR BOYFRIEND MADE YOU COME HERE

User: He says I’m depressed much of the time.

Chatbot: I AM SORRY TO HEAR YOU ARE DEPRESSED

Weizenbaum published this sample exchange in a journal article that explained how the chatbot worked. The software was relatively simple. It looked at the user input and applied a set of rules to generate a plausible response. He called the program Eliza, after Eliza Doolittle in Pygmalion. The cockney flower girl in George Bernard Shaw’s play uses language to produce an illusion: she elevates her elocution to the point where she can pass for a duchess. Similarly, Eliza would speak in such a way as to produce the illusion that it understood the person sitting at the typewriter.

“Some subjects have been very hard to convince that Eliza (with its present script) is not human,” Weizenbaum wrote. In a follow-up article that appeared the next year, he was more specific: one day, he said, his secretary requested some time with Eliza. After a few moments, she asked Weizenbaum to leave the room. “I believe this anecdote testifies to the success with which the program maintains the illusion of understanding,” he noted.

Read the rest of this article at: The Guardian

When the world’s first internet cafe, Cafe Cyberia, first opened its doors in London’s West End in September 1994, its founders could never have imagined what they’d unleashed.

Internet cafes — cheap, accessible venues where just about anyone could explore cyberspace in its infancy — spread slowly across the world at first, and then snowballed in popularity. In the spring of 1996, Sri Lanka got its first two internet cafes: the Cyber Cafe, and the Surf Board. A few months later, Kuwait’s first internet cafe launched with 16 PCs. In 1999, a travel guide promised readers a list of 2,000 cafes in 113 countries.

Within a couple years, it was estimated that there were more than 100 internet cafes in Ghana alone. BusyInternet opened the largest internet cafe in Accra, boasting 100 screens. By 2002, there were more than 200,000 licensed internet cafes in China, and still more operating under the table.

“They were mushrooming,” Ricardo Gomez, an associate professor at the University of Washington who conducted a definitive survey of public internet access in the late 2000s, told Rest of World.

Internet cafes were more than just places to log on. They emerged in the waning years of the 20th century — a post-Cold War moment full of techno-optimism. Sharing a global resource like the internet “was going to bring different people in different cultures together in mutual understanding,” historian and author Margaret O’Mara told Rest of World. It was an era in which, both physically and digitally, “people were moving across borders that before were very difficult, if not impossible, to cross.”

Read the rest of this article at: Rest Of The World

Bruce Willingham, fifty-two years a newspaperman, owns and publishes the McCurtain Gazette, in McCurtain County, Oklahoma, a rolling sweep of timber and lakes that forms the southeastern corner of the state. McCurtain County is geographically larger than Rhode Island and less populous than the average Taylor Swift concert. Thirty-one thousand people live there; forty-four hundred buy the Gazette, which has been in print since 1905, before statehood. At that time, the paper was known as the Idabel Signal, referring to the county seat. An early masthead proclaimed “INDIAN TERRITORY, CHOCTAW NATION.”

Willingham bought the newspaper in 1988, with his wife, Gwen, who gave up a nursing career to become the Gazette’s accountant. They operate out of a storefront office in downtown Idabel, between a package-shipping business and a pawnshop. The staff parks out back, within sight of an old Frisco railway station, and enters through the “morgue,” where the bound archives are kept. Until recently, no one had reason to lock the door during the day.

Three days a week (five, before the pandemic), readers can find the latest on rodeo queens, school cafeteria menus, hardwood-mill closings, heat advisories. Some headlines: “Large Cat Sighted in Idabel,” “Two of State’s Three Master Bladesmiths Live Here,” “Local Singing Group Enjoys Tuesdays.” Anyone who’s been cited for speeding, charged with a misdemeanor, applied for a marriage license, or filed for divorce will see his or her name listed in the “District Court Report.” In Willingham’s clutterbucket of an office, a hulking microfiche machine sits alongside his desktop computer amid lunar levels of dust; he uses the machine to unearth and reprint front pages from long ago. In 2017, he transported readers to 1934 via a banner headline: “NEGRO SLAYER OF WHITE MAN KILLED.” The area has long been stuck with the nickname Little Dixie.

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

LUCY

I am the daughter of a newspaperman.

Throughout my life, I’ve used a version of this sentence to talk about myself: in college application essays and internship cover letters, on first dates, and now in this story. At 32 years of age, my pride in stating what is a core fact of my existence hasn’t diminished.

My dad, Joe Sexton, began his career as a sportswriter at the City Sun in Brooklyn, New York. One of his earliest stories was about the Rikers Island Olympics. He later covered a young Mike Tyson; he sat ringside, and had the blood on his clothes to prove it. When he made it to the sports desk at The New York Times, he spent years terrorizing the Mets and their ownership for crimes of mediocrity and incompetence.

Then, at 34, Joe was suddenly a single father of two daughters. I was just shy of three at the time. If memory can be trusted, I have a few vivid images—random snapshots captured through my toddler’s eyes—of the good and the bad: my tiny cowboy boots against shimmering asphalt; a stash of candies in a porcelain pitcher; being in a dark, frightening hotel room. When it became clear that my mother had demons she would need to wrestle with alone, Joe gained custody of me and my sister.

Here’s another memory: a late-night bottle of milk Joe gave me while friends, presumably fellow reporters, were visiting our house. Joe was simultaneously holding his family together and building a high-profile media career. Work meant that he was on the clock 24/7, and the Times became a second home for our family, a place where we were surrounded by people rooting for the three of us. When Joe jumped from the sports desk to the metro section, the newsroom served as a backup babysitter. When a story demanded that Joe’s feet hit the pavement, two little girls weren’t the worst accessories in pursuit of a quote.

Joe helped the Times garner a fistful of Pulitzer Prizes and covered everything from 9/11 (he dropped me off at school in Brooklyn that morning, and I didn’t see him for days afterward), to the sex-abuse scandal at Penn State, to the ousting of two New York governors. Eight years and more stories and prizes followed at ProPublica, the nonprofit news organization.

Read the rest of this article at: The Atavist Magazine