Inside Pharrell’s World at Louis Vuitton—and the New Era of Fashion He’s Leading

Pharrell Williams has a pimple. There’s a bandage on his chin, and immediately after introducing myself, I ask him, “What happened?” And he says in the nonchalant, melodious voice I’ve heard approximately 1 billion times on speakers and in headphones but did not expect to be so perfectly his in person: “Oh, just a pimple.”

He just turned 50 and his skin has the texture and tone of a nourished and well-hydrated 22-year-old. Upon clocking the bandage, I thought maybe one of his four children had caught him with a headbutt. Maybe he fell skateboarding. I did not in a thousand years expect him to tell me that under the bandage he had hidden a pimple. And immediately I feel like a jerk for calling attention to it.

But Pharrell does not seem perturbed by my comment, or by the blemish or the bandage. He is full of humility. He is open and honest and ready to share himself—and his imperfections—with the world.

We were in a vast parking lot in Pharrell’s hometown of Virginia Beach, amid a carnival of trailers and trucks that served as the backstage area for the now-annual three-day music festival called Something in the Water that he hosts right on the sand. It was late April, a momentous time for Pharrell. He was just two months into his new job as the men’s creative director of Louis Vuitton, and enormous questions were swirling about what the superstar producer would do with the keys to a global luxury superbrand.

Read the rest of this article at: GQ

When Trucks Fly

A monster trucker is the kind of person who has a favorite type of dirt. I’ve heard drivers describe a track as fluffy, sticky, loose, tacky, grippy, greasy, slick, crumbly, powdery, bone-dry, baked out, dead, loamy, earthen, sandy, slidey, soupy, snotty, and marshmallowy. Everyone understands the distinctions. They obsess over them like vintners obsess over terroir. The first time I met an employee of Monster Jam, which sells millions of tickets to its monster-truck shows every year, the first thing she told me was that the company owns more dirt, she thinks, than anyone else in the world.

Monster Jam runs events in about a hundred and thirty stadiums and arenas annually, on six continents. This requires building a hundred and thirty elaborate, temporary tracks, with massive jumps and ramps constructed out of dirt, like sandcastles for a giant. Rallies, these days, are less demolition-derby crash-fests than aerial acrobatic shows involving twelve-thousand-pound vehicles. It’s expensive to source and truck in enough dirt to fill a stadium, so the company stashes a big pile near each venue, to be used year after year. For the Meadowlands’ MetLife Stadium, in New Jersey, which Monster Jam visited a couple of months ago, the dirt lives in a nearby Superfund site: a decontaminated corner of an old cologne factory. When I showed up on the Thursday morning before the event, a procession of dump trucks was shuttling between the site and the stadium.

‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’ gives us a sense of the poet’s mode: he asks question after question about the urn, not to uncover facts or ‘answers’, but rather to sustain his experience of wonder and curiosity. There is something else, too. Keats is not only speculating, inventing and describing, he’s also seeking out the effects of his imaginative engagement with the urn itself. What exactly are these effects? And is there something about this particular mode of engaging with images and objects – with art – that could prove valuable in other contexts.

“It’s so hard to find good dirt,” Daniel Allen, who’s known informally as Monster Jam’s senior director of dirt, told me. “And by no stretch is the dirt in this area great.” Allen, who is thin and wiry, got the Meadowlands dirt a decade ago from a housing developer nearby. “A Russian guy, Vlady something,” Allen said. “You could barely even understand this guy, but he had good dirt.” That first time, Allen’s crew had taken possession of about half of Vlady’s dirt when bad storms hit, and every construction pit in the area shut down. The show was in a couple of days. Allen had to improvise. “Our dirt in Philadelphia is stored behind Lincoln Financial Stadium, under I-95. I knew it was perfectly good and dry. So we took a night of hauling, and we brought over three thousand yards of clay at night, truck after truck, hundreds of truckloads.”

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

In 1967, the physicist John Wheeler was giving a lecture about a mysterious and startling phenomenon in deep space that the field was just beginning to understand. But it didn’t have a great name to match. Wheeler and his audience were equally tired of hearing “gravitationally completely collapsed object” over and over, so someone threw out an idea for a different name. A few weeks later, at another conference, Wheeler debuted the suggestion: black hole. And it’s perfect, isn’t it? What else would you call a dark abyss that swallows light and matter and doesn’t let go?

Decades later, black holes—invisible, impenetrable, and many light-years away—are more familiar to us than ever before. We know that supermassive versions sit at the center of most galaxies, including our own Milky Way. In 2019, we even got pictures that show a black hole as an imposing shadow against the glow of cosmic material. Scientists have detected the gravitational ripples that result when black holes smash into each other; the entire cosmos, we recently learned, might be humming with the force of such collisions. The list goes on.

Read the rest of this article at: The Atlantic

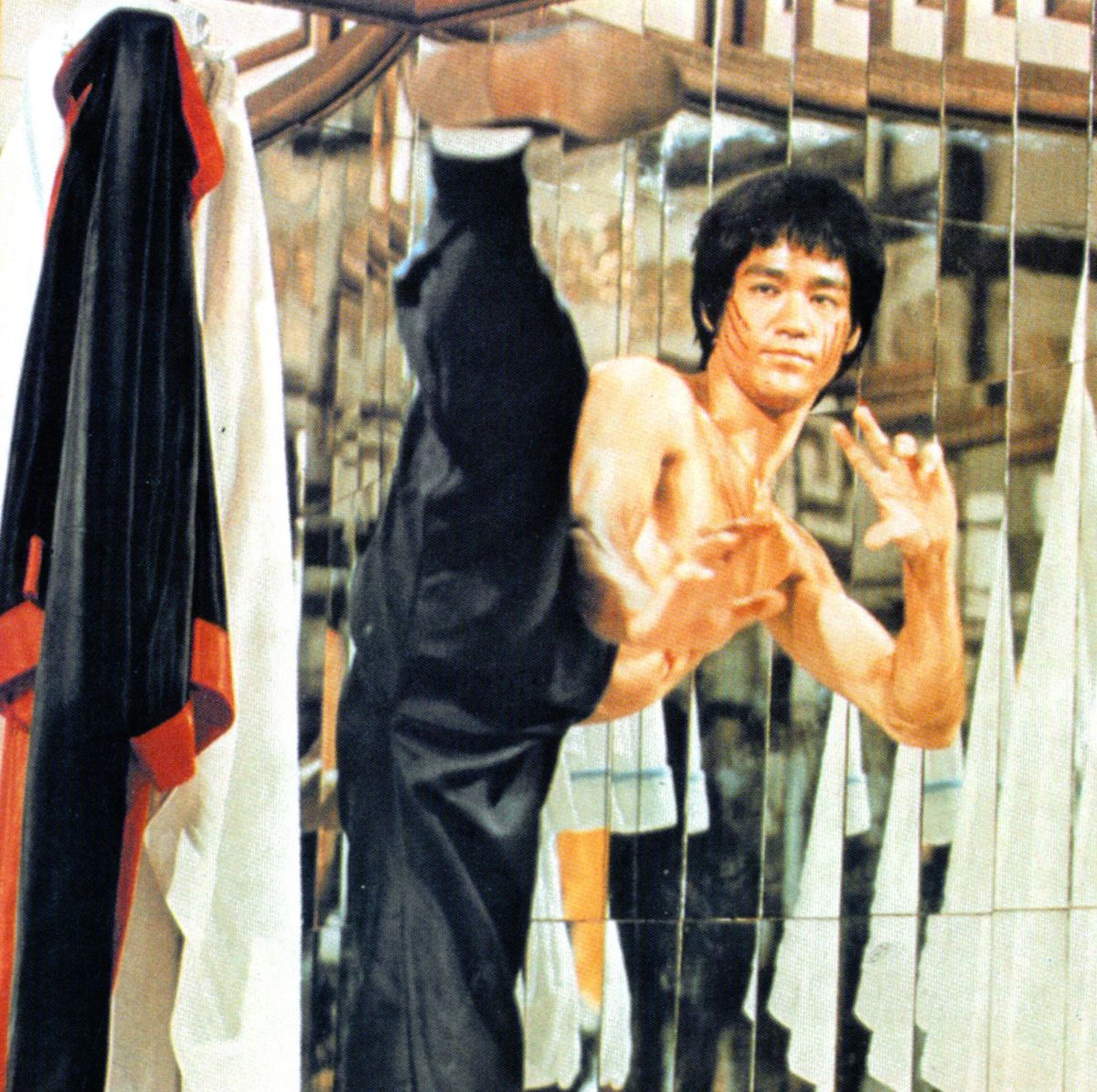

The Immortality of Enter the Dragon

Bruce Lee was a god amongst men. He commanded impossible strength, charisma, and vigor—and Enter the Dragon captured it all on celluloid for posterity. When the film hit theaters in August 1973, action cinema changed forever; its awesome might only added to its leading man’s evergreen mystique. But Lee never had the chance to witness Enter the Dragon‘s impact. He died of a cerebral edema at the age of 32, a month before the movie’s release. Fifty years later, Enter the Dragon still spellbinds audiences—especially Lee’s daughter, Shannon, who tells me she loves merely listening to the film.

“It’s his own voice in the film, as opposed to being dubbed over,” she explains over recent video call. “It holds a special place in my heart just in terms of connecting with my father.” Of all of Lee’s films, including Fist of Fury, The Game of Death, and The Way of the Dragon—with its all-time showdown between Bruce Lee and Chuck Norris—Shannon says that his visage in Enter the Dragon is “the closest [thing] to the father that I knew.”

As Enter the Dragon celebrates its 50th anniversary—and theaters across the globe hold screenings of the film—Shannon is reflecting on the movie that made her father famous everywhere. “This may sound self-serving, but I think it’s because of Bruce Lee the movie is phenomenal,” Shannon says, believing her father’s performance is timeless amidst the era’s abundance of funky ’70s kitsch. “He still electrifies and jumps off the screen, and is just so badass. It’s a fun movie—and he brings the fun.”

On August 17, 1973, Enter the Dragon swept its competition to become one of the highest-grossing movies of the year. A spy film in the style of a James Bond adventure, Lee plays a secret agent who infiltrates a martial-arts tournament on an exotic island to take down a criminal mastermind. Adjusted for inflation, Enter the Dragon grossed $150 million in 1973. The number isn’t too shabby, considering Enter the Dragon faced stiff competition from other artistic giants such as Westworld, American Graffiti, The Sting, and The Exorcist.

Read the rest of this article at: Esquire

How Carl Linnaeus Set Out to Label All of Life

For the Tyrannosaurus rex, as for Elvis and Jesus, being extremely dead has proved no obstacle to ongoing fame. Last seen some sixty-six million years ago, before an asteroid wiped out three-quarters of the life-forms on earth, it is nonetheless flourishing these days, thanks in large part to Michael Crichton, Steven Spielberg, and elementary-school children all over the world. In my experience, such children not only can rattle off the dinosaur’s vital statistics—fifteen feet tall, forty feet long, twelve thousand pounds—but will piously correct any misinformation advanced by their paleontologically passé elders. And here is the most surprising thing that all those ten-year-olds plus pretty much everyone else on the planet know about T. rex: the creature’s proper scientific name.

That name is itself properly called a binomen, the smallest unit in the vast system known as binomial nomenclature. You’ll remember the gist from basic biology: to eliminate any possible overlap or confusion, every species on the planet, whether extant or extinct, is assigned a full name, consisting of its genus (used here as a surname of sorts, indicating to what other creatures it is related) followed by its species, with both halves Latinized, and the genus sometimes reduced to just an initial, like Josef K. Thus: Tyrannosaurus rex, or T. rex, of the genus Tyrannosaurus and the species rex, known in full translation as King of the Tyrant Lizards.

Binomial names are extremely important to scientists but rarely used by the rest of us. Apart from T. rex, I am aware of only a few that crop up in everyday conversation. We know our own full name, of course—Homo sapiens, the last surviving species in a genus that once included Homo habilis, Homo floresiensis, Homo neanderthalensis, and several others—as well as that of the boa constrictor, a snake of the genus Boa, and E. coli, a bacterium of the genus Escherichia. You could argue based on those two examples plus T. rex that we speak respectfully of species that are potentially dangerous to us—not a bad policy, but also not a good argument, since a fourth example that comes to mind is Aloe vera. Also, almost no one outside scientific circles calls the great white shark Carcharodon carcharias.

Inside scientific circles, however, binomial nomenclature still rules the day, lending concision and clarity to fields ranging from molecular biology to evolutionary ecology. It was developed, as you might also remember from your school days, by the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus in the middle of the eighteenth century, an era that was in thrall to the mighty project of trying to systematize all of nature. Appropriately for his line of work, Linnaeus’s name remains widely known, and he is hailed in his country of origin as his own kind of rex—the King of Flowers. But the details of his life and the nature of his scientific contributions are both less contemplated and more complicated, with his staunchest defenders characterizing him as an Enlightenment-era genius who paved the way for Charles Darwin, and his fiercest critics casting him as one of history’s most influential racists. A new biography, “The Man Who Organized Nature” (Princeton), written by Gunnar Broberg and translated from the Swedish by Anna Paterson, attempts to provide the fullest possible account of his life yet fails to grapple with the fundamental question it raises: if categorization is crucial to making sense of the world, how should we classify Carl Linnaeus?

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker