In recent months, the signs and portents have been accumulating with increasing speed. Google is trying to kill the 10 blue links. Twitter is being abandoned to bots and blue ticks. There’s the junkification of Amazon and the enshittification of TikTok. Layoffs are gutting online media. A job posting looking for an “AI editor” expects “output of 200 to 250 articles per week.” ChatGPT is being used to generate whole spam sites. Etsy is flooded with “AI-generated junk.” Chatbots cite one another in a misinformation ouroboros. LinkedIn is using AI to stimulate tired users. Snapchat and Instagram hope bots will talk to you when your friends don’t. Redditors are staging blackouts. Stack Overflow mods are on strike. The Internet Archive is fighting off data scrapers, and “AI is tearing Wikipedia apart.” The old web is dying, and the new web struggles to be born.

The web is always dying, of course; it’s been dying for years, killed by apps that divert traffic from websites or algorithms that reward supposedly shortening attention spans. But in 2023, it’s dying again — and, as the litany above suggests, there’s a new catalyst at play: AI.

The problem, in extremely broad strokes, is this. Years ago, the web used to be a place where individuals made things. They made homepages, forums, and mailing lists, and a small bit of money with it. Then companies decided they could do things better. They created slick and feature-rich platforms and threw their doors open for anyone to join. They put boxes in front of us, and we filled those boxes with text and images, and people came to see the content of those boxes. The companies chased scale, because once enough people gather anywhere, there’s usually a way to make money off them. But AI changes these assumptions.

Read the rest of this article at: The Verge

What is the most uninformative statement that people are inclined to make? My nominee would be “I love to travel.” This tells you very little about a person, because nearly everyone likes to travel; and yet people say it, because, for some reason, they pride themselves both on having travelled and on the fact that they look forward to doing so.

The opposition team is small but articulate. G. K. Chesterton wrote that “travel narrows the mind.” Ralph Waldo Emerson called travel “a fool’s paradise.” Socrates and Immanuel Kant—arguably the two greatest philosophers of all time—voted with their feet, rarely leaving their respective home towns of Athens and Königsberg. But the greatest hater of travel, ever, was the Portuguese writer Fernando Pessoa, whose wonderful “Book of Disquiet” crackles with outrage:

I abhor new ways of life and unfamiliar places. . . . The idea of travelling nauseates me. . . . Ah, let those who don’t exist travel! . . . Travel is for those who cannot feel. . . . Only extreme poverty of the imagination justifies having to move around to feel.

If you are inclined to dismiss this as contrarian posturing, try shifting the object of your thought from your own travel to that of others. At home or abroad, one tends to avoid “touristy” activities. “Tourism” is what we call travelling when other people are doing it. And, although people like to talk about their travels, few of us like to listen to them. Such talk resembles academic writing and reports of dreams: forms of communication driven more by the needs of the producer than the consumer.

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

Oh, jake,” brett said, “we could have had such a damned good time together.” So writes Ernest Hemingway in “The Sun Also Rises”. “Ahead was a mounted policeman in khaki directing traffic. He raised his baton. The car slowed suddenly pressing Brett against me. ‘Yes,’ I said. ’isn’t it pretty to think so?’”

It is pretty to think so, and if Hollywood got its mitts on Hemingway’s oeuvre today, the story would not end with such aching futility. As the baton came down the scene would jump to another world, or timeline, where Brett and Jake—he, in this other reality, having dodged that emasculating war wound—are rolling in the hay, then (wave of the baton) another reality in which Brett, now a matador, is bringing a bull to its knees and then (this time a wave of her red cape) another where she is helping a wrinkled Cuban fellow in a tiny boat reel in a giant fish, with a heave from the Incredible Hulk and, inevitably, his chuckling buddy Thor.

Read the rest of this article at: The Economist

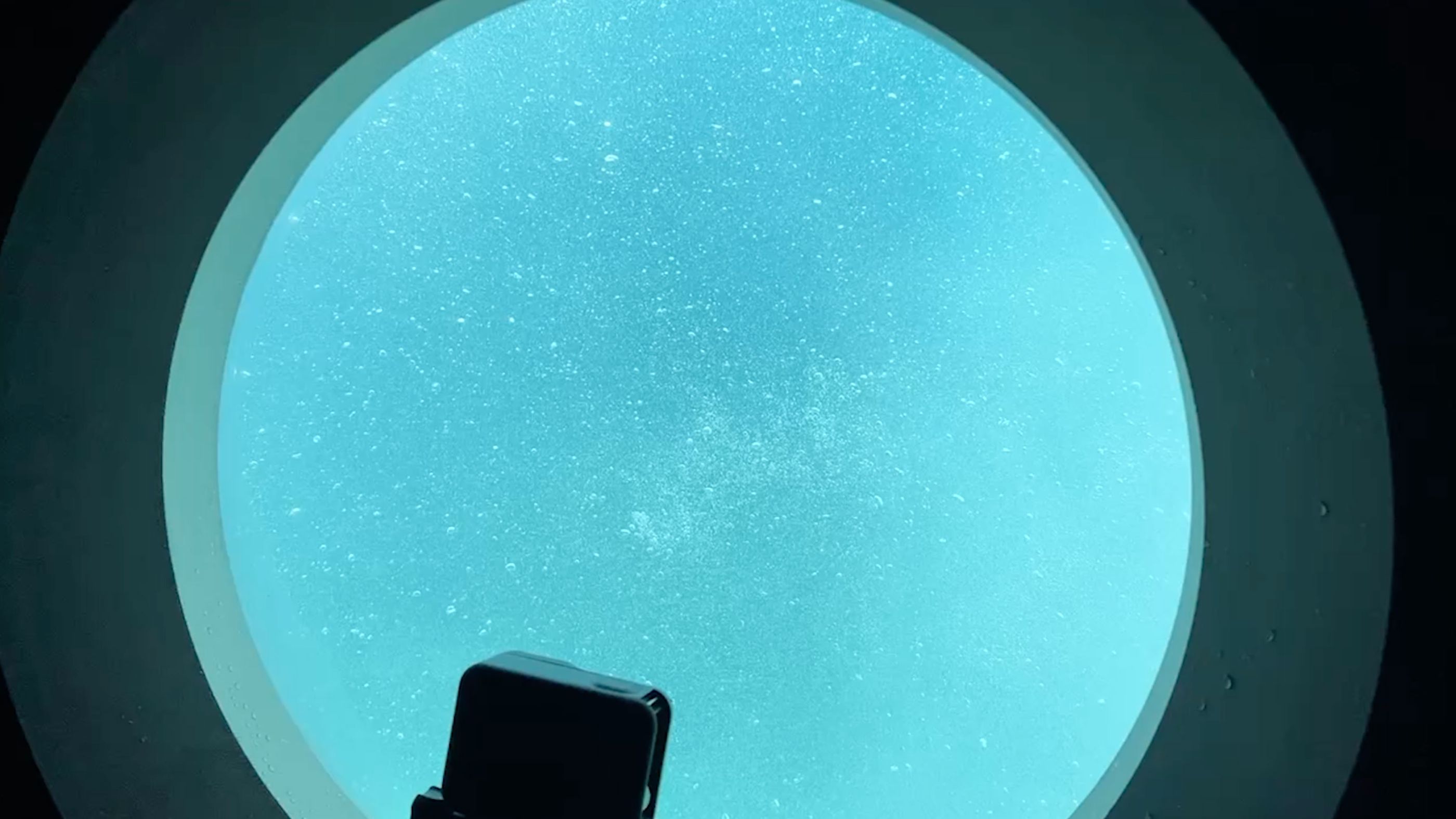

Last summer, for a CBS News Sunday Morning story, I joined OceanGate for a dive on its Titan submersible. I never saw the Titanic. We were only 37 feet below the waves when mission control aborted our dive.

At the time, I thought the reason was pretty dumb: Two capsule-shaped black floats, poorly tied to the sub’s launching platform, had come loose. The floats weren’t part of the sub. They’d have no effect on the dive itself. Who cared about the stupid platform? Let’s GO!

Now, of course, it all looks different. Now, I’m sick to my stomach. Now, I feel like I won at Russian roulette. Three dives later, the Titan imploded and killed the five people onboard.

You can think about our dive’s cancellation in two ways (well, I can). One take: You should never have gotten on that thing. Bad knots should have been a red flag. The other: They’d rather cancel a dive, even for something small, than risk lives. That’s a safety culture.

And right there, in microcosm, is the debate I’ve had with myself for the past year. Stockton Rush, who died in the implosion, was OceanGate’s CEO and the Titan’s designer. Was he a bold innovator, the Elon Musk of submersibles, advancing 50-year-old ideas with modern technologies?

Or was he a con man who cut corners to save money at the cost of his customers’ lives?

This is a journal of the events of that expedition and the evolution of my thinking. It’s also my chance to introduce some new information into the conversation — details that have been missing from the thousands of hours of Titan news coverage so far.

Read the rest of this article at: New York Magazine

She arrives, queenlike, in a designer Italian overcoat, high collar, and sunglasses, lipstick smile at once warm and fixed. An aide guides her by the elbow, security detail in tow, to the dining room of Pier 23, an old-school San Francisco tavern in the Embarcadero with a stuffed marlin on the wall and a multistory cruise ship idling outside. Two workmen in dayglow safety coats crane their necks from the bar to see Nancy Pelosi, Madam Speaker, doyenne of San Francisco, bête noire of the right.

Pelosi removes her shades and requests a bowl of vanilla ice cream with chocolate sauce on top. “A lot of chocolate,” she orders.

I ask her if she’s been briefed on the subject of today’s interview. Her press man told her I was writing “about California,” she says with a knowing twinkle, “and how magnificent it is, and how it is the leader in the world.”

Yes. And no.

Once in a while, an East Coast journalist will come out to California to find out what’s happening in the land of dreams. As Los Angeles goes, so goes the nation; if San Francisco loses its charm, what then? “It’s what’s coming next for you,” Pelosi says, portentously.

Earlier that afternoon, I’d walked through the Tenderloin and seen drug addicts splayed out on street corners and a hundred human tragedies strewn across UN Plaza, City Hall looming helplessly in the background. Dickens meets Dante. “Oh, it’s sad,” Pelosi remarks. “It’s worse now.”

That morning, after a freak snowfall, I’d hiked to the top of Mount Tamalpais in Marin County to survey the preposterous beauty of California and found a snowman with a frown carved into its face. “A couple of days ago was the coldest day in, like, 150 years,” Pelosi notes. “Well, it is what it is,” she shrugs, and tells me how the Spanish missionaries used to follow their livestock to the warmest grazing area with water and then build their settlement, which is how San Francisco got the Mission District. No snowmen down there.

Read the rest of this article at: Vanity Fair

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24390468/STK149_AI_Chatbot_K_Radtke.jpg)