Ryan Gosling subscribes to what he calls an escape-room style of being an actor. This is a little theoretical, because he’s never actually been to an escape room, and he’s not totally sure what happens inside of them. “Maybe I should do one,” he says, “to see if this really works.” But the general idea is: You’re thrown into a particular set of circumstances and you’ve got to find your way out. Maybe you show up on set one day and it’s raining when it’s not supposed to be raining, Gosling says, “or this person doesn’t want to say any of that dialogue, or the neighbor’s got a leaf blower and they’re not turning it off.” What do you do next?

Over time, Gosling has discovered that this approach might apply to more than just acting. Maybe, for instance, you’re a kid growing up in a town you don’t want to be in and you’re trying to locate an exit. Maybe you’re looking for something you can’t put into words and you make movies to try to pin down whatever it is you’re looking for. Maybe you’re a person who never envisioned raising a family and then you meet the person who changes, in some radical way, how you see yourself and your future. Life comes at you, in all its unanticipated and startling particulars; the thing that makes you an artist is the way you respond.

And being open to the unexpected has served Gosling well. When he was young, his first real breakthrough came in a movie, 2001’s The Believer, about a Jewish kid from New York who becomes a neo-Nazi. Gosling was none of these things, a fact that the director, Henry Bean, turned out to like—“The fact that I wasn’t really right for it was exactly why he thought I was right for it,” Gosling says. A few years later, when Gosling was auditioning for The Notebook, he says, the director, Nick Cassavetes, “straight up told me: ‘The fact that you have no natural leading man qualities is why I want you to be my leading man.’ ” Gosling got the part; he’s been a leading man ever since.

Read the rest of this article at: GQ

Twenty-one years ago this month, on September 6, 1992, the decomposed body of Christopher McCandless was discovered by moose hunters just outside the northern boundary of Denali National Park. He had died inside a rusting bus that served as a makeshift shelter for trappers, dog mushers, and other backcountry visitors. Taped to the door was a note scrawled on a page torn from a novel by Nikolai Gogol:

ATTENTION POSSIBLE VISITORS.

S.O.S.

I NEED YOUR HELP. I AM INJURED, NEAR DEATH, AND TOO WEAK TO HIKE OUT OF HERE. I AM ALL ALONE, THIS IS NO JOKE. IN THE NAME OF GOD, PLEASE REMAIN TO SAVE ME. I AM OUT COLLECTING BERRIES CLOSE BY AND SHALL RETURN THIS EVENING. THANK YOU,

CHRIS McCANDLESS

AUGUST ?

From a cryptic diary found among his possessions, it appeared that McCandless had been dead for nineteen days. A driver’s license issued eight months before he perished indicated that he was twenty-four years old and weighed a hundred and forty pounds. After his body was flown out of the wilderness, an autopsy determined that it weighed sixty-seven pounds and lacked discernible subcutaneous fat. The probable cause of death, according to the coroner’s report, was starvation.

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

How Adidas Uncanceled Yeezy

On Wednesday, for the first time in over seven months, sneakerheads put aside their love-hate relationship with Ye, the artist formerly known as Kanye West, and resumed a love-hate relationship with his Yeezy sneaker brand—which is to say, loving to buy them and hating to miss out. As Adidas sold off some of the Yeezy shoes left over from its partnership with Ye, which ended last October, fans turned to social media for a familiar ritual of shared delight and disappointment. On Twitter, some complained about losing the raffles that determine who gets the chance to buy a pair of Yeezys. Others worried how much it might cost them to win every raffle they entered: “I’m in four different draws for some Yeezys,” @theregoesrhodes tweeted. “if I hit on all four, imma have to work four 24 hour shifts in a row smh.” Most sneakerheads seemed to view the drop as an apolitical return to business as usual, though some Ye fans clearly saw it as a kind of vindication for the embattled rap star and fashion mogul. A few even thanked those who had “canceled” Ye for making it easier to cop a pair of Yeezys.

If the odds have improved for Yeezy fans, however, it probably has less to do with supposed cancel culture than with the generous supply on offer. After dropping the first few styles and colorways around 5 am EST, Adidas continued to roll out fresh silhouettes and colorways throughout the day. The direct-to-consumer mega-drop featured no less than four different colorways for the Yeezy 350 v2, one or more each for the 380, 450, 500, 700 v1, 700 v2, plus Yeezy foam runners and slides. At least one new style has been offered through the app this morning, while others have fresh countdown clocks indicating a re-stock will be offered tomorrow.

Read the rest of this article at: GQ

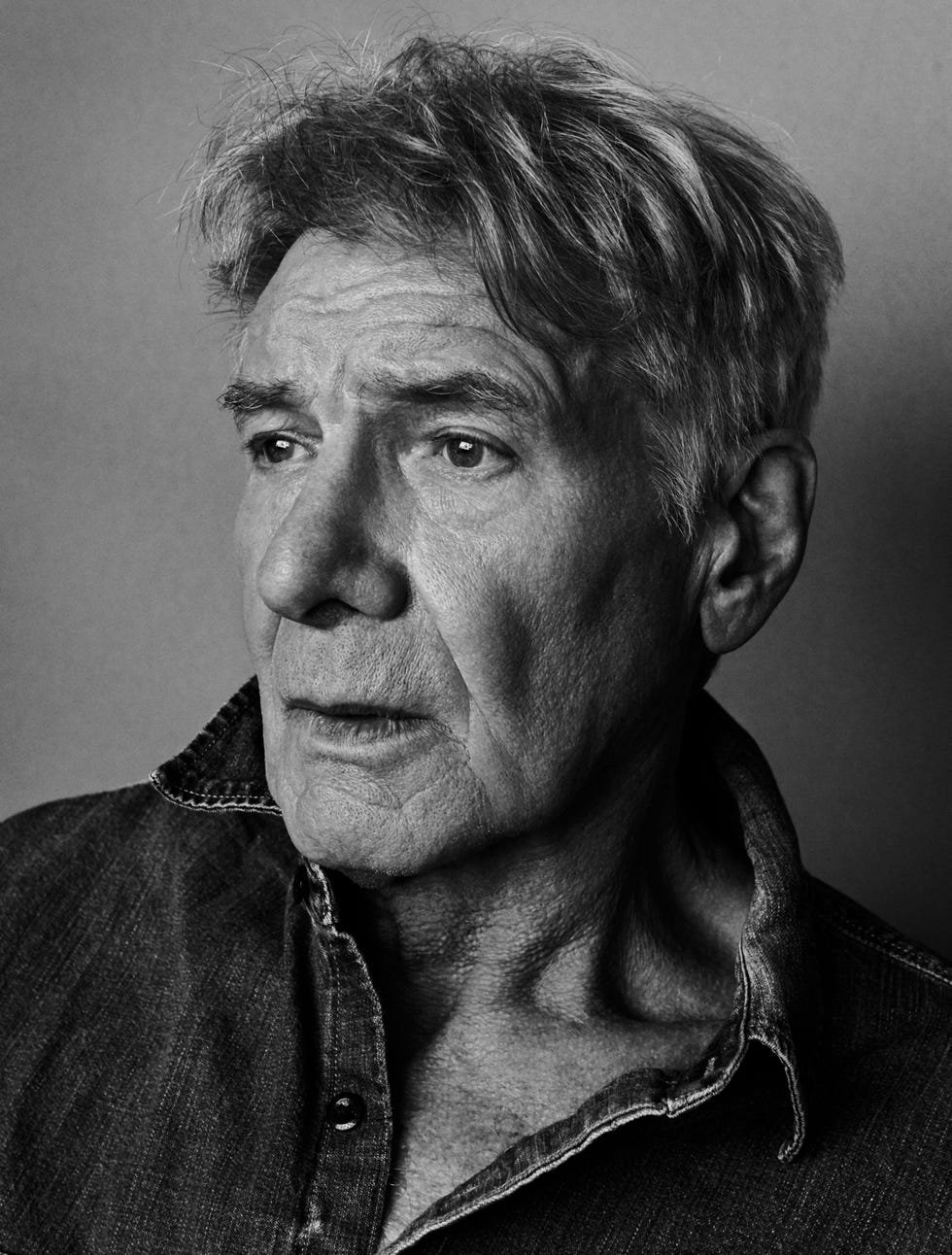

The last time I spoke with him was on the phone, three weeks after we drank bourbon at his house. We sat at the bar in what I’ll call the family room, a gleaming wooden bar with the bottles lined up behind, organized in neat rows by type of liquor. We ate Emmentaler cheese that Harrison Ford had sliced in the kitchen with a silver cheese knife and arranged on a plate with a handful of wheat crackers. That was in Los Angeles, where he lives when he’s not at his most-of-the-time home, the ranch in Wyoming that he bought in the eighties.

He was now in Atlanta. His voice, the unmistakable rich, low grumble, came through the phone obscured by some shuffling in the background.

“How you doing?” he asked.

In movies, Ford’s voice can tremble and quiver at low volume, just enough to communicate a terrifying degree of urgency, like if you don’t do what he says right now, people could die.It can jump to a sharp holler when things get even worse. His voice can be tender. It can be funny and biting.

On the phone, he just sounded like a guy on a Sunday afternoon. The background shuffling quieted.

“I’m learning a bunch of lines for tomorrow,” he said, exhaling.

Read the rest of this article at: Esquire

When Vincent Richardson was 14 years old, he wore a police uniform into Chicago’s Third District Grand Crossing police station and reported for duty. It was January 24th, 2009, and he told officers he’d been assigned by another district to work a shift there. An intake officer issued Vincent a police radio and ticket book; then, the officer assigned Vincent a partner and a police cruiser.

Over the next five hours, they drove around the South Side of Chicago monitoring hot spots and responding to calls from dispatch. Vincent helped with traffic stops. He communicated with dispatchers using specific criminal codes about activities on the beat. He even assisted in an arrest helping to place handcuffs on someone suspected of violating a protective order.

He did this as an eighth grader. His uniform was a costume. And no one realized he was just a kid pretending to be a cop.

Vincent and his partner returned to Grand Crossing station later that evening. The captain on duty noticed the small, clean-shaven officer and asked Vincent to produce a badge. He couldn’t, of course. The captain searched him and discovered Vincent’s gun holster was empty; he’d crammed a newspaper into his body armor bag to make it look full. The captain placed Vincent under arrest and charged him as a juvenile with the misdemeanor offense of impersonating a police officer.

Read the rest of this article at: The Verge

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24690946/236623_Kid_Cop_MOMatic_001.jpg)