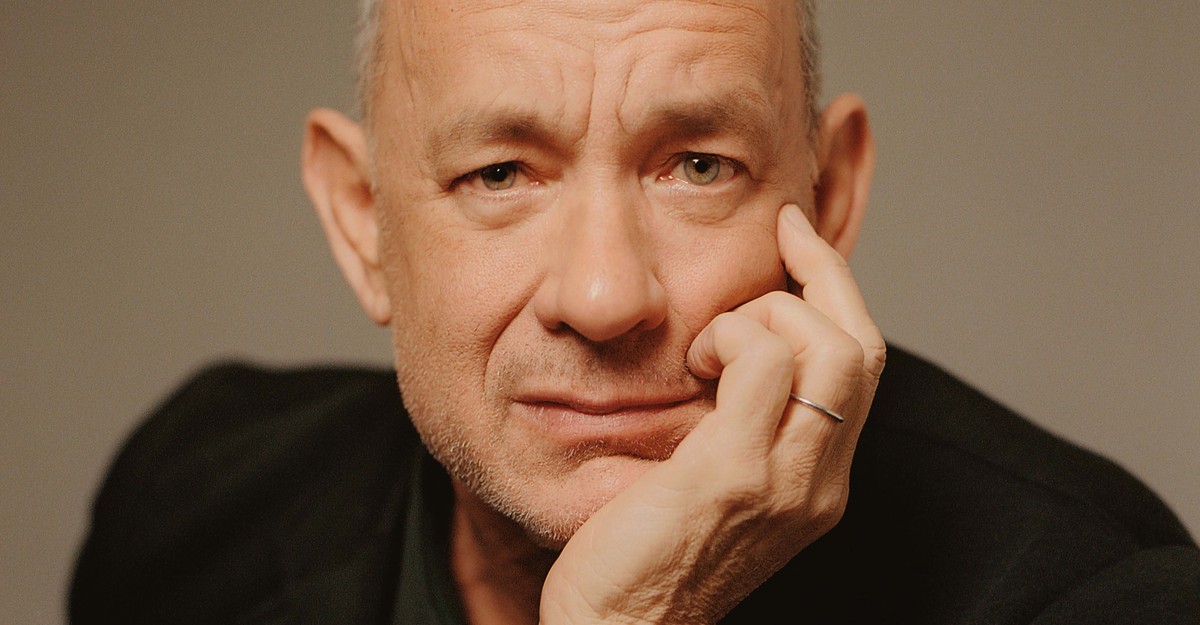

There is a particular circumstance deep in Tom Hanks’s past that he thinks may explain something significant about the person he is now. One that suggests how, before all of this—before everything he would achieve and come to represent in the world, before he had even begun to work out what talents he might have and how he might best use them—he was already well on the way to becoming who he would be.

As a child, several times a year, Hanks would take a long journey on a Greyhound bus, heading to and from the small Northern California town of Red Bluff. He was often alone, and he always sat by the window. In Red Bluff, Hanks would stay with his mother, Janet; after his parents’ marriage ruptured when he was 5, he never lived with her, but on holidays he’d visit. And so, from when he was 8 until he was 17, four or so hours each way, he’d take this ride.

Those journeys, they released something within him. Sometimes he read a little, maybe a comic, maybe a book, but mostly he’d stare out into the passing world. He’d watch the broken sine wave of the telephone lines, looping on and on and on for miles, then veering away, then rejoining the bus’s path. He’d see a barn, wonder what was on the other side. A house would flash by; he’d imagine who lived in it. Some figures standing outside: What were they doing? A plane up in the clear sky: All those people, where were they going and what were they thinking? The couple in that car as the Greyhound passed, the guy by himself in the truck, that station wagon loaded up with kids in the back, that locomotive on the train tracks …

Read the rest of this article at: The Atlantic

Suppose a large inbound asteroid were discovered, and we learned that half of all astronomers gave it at least 10% chance of causing human extinction, just as a similar asteroid exterminated the dinosaurs about 66 million years ago. Since we have such a long history of thinking about this threat and what to do about it, from scientific conferences to Hollywood blockbusters, you might expect humanity to shift into high gear with a deflection mission to steer it in a safer direction.

Sadly, I now feel that we’re living the movie “Don’t look up” for another existential threat: unaligned superintelligence. We may soon have to share our planet with more intelligent “minds” that care less about us than we cared about mammoths. A recent survey showed that half of AI researchers give AI at least 10% chance of causing human extinction. Since we have such a long history of thinking about this threat and what to do about it, from scientific conferences to Hollywood blockbusters, you might expect that humanity would shift into high gear with a mission to steer AI in a safer direction than out-of-control superintelligence. Think again: instead, the most influential responses have been a combination of denial, mockery, and resignation so darkly comical that it’s deserving of an Oscar.

When “Don’t look up” came out in late 2021, it became popular on Netflix (their second-most-watched movie ever). It became even more popular among my science colleagues, many of whom hailed it as their favorite film ever, offering cathartic comic relief for years of pent-up exasperation over their scientific concerns and policy suggestions being ignored. It depicts how, although scientists have a workable plan for deflecting the aforementioned asteroid before it destroys humanity, their plan fails to compete with celebrity gossip for media attention and is no match for lobbyists, political expediency and “asteroid denial.” Although the film was intended as a satire of humanity’s lackadaisical response to climate change, it’s unfortunately an even better parody of humanity’s reaction to the rise of AI. Below is my annotated summary of the most popular responses to rise of AI:

Read the rest of this article at: Time

For the past 70 years, one tradition has brought Europeans (and many from other nations) to their TV screens to marvel at the performances by dozens of singers: the Eurovision Song Contest.

About 200 million viewers take pride in the performers representing their nations while cheering and picking their favorites among the competition. The celebration of unity and diversity is tinged with politics in what’s supposed to be an apolitical contest.

Many in the U.S. were first introduced to the international song competition during the COVID-19 pandemic through Netflix’s hit parody “Eurovision Song Contest: The Story of Fire Saga” starring Will Ferrell and Rachel McAdams.

Read the rest of this article at: USA Today

You know the scene in American Psycho in which murdery investment banker Patrick Bateman, played by a young Christian Bale, strides stoically into his office while Katrina and the Waves’ “Walking on Sunshine” blares through his headphones? It’s been playing on an endless loop on TikTok for months.

While there’s nothing new to TikTok breathing life into pop-culture relics — take, for example, the resurgence of Kate Bush’s 1985 hit “Running Up That Hill (A Deal With God)” after the track’s needle drop on Stranger Things — the app’s meme-ing of the 2000 thriller isn’t actually about the film or the soundtrack. It’s about Gen Z being horny for Christian Bale.

Read the rest of this article at: The Cut

“There’s no such thing as a good landlord” is a rallying cry of angry renters. In the future, it might be conventional morality that it’s simply wrong to own land.

In our times, owning land seems as natural as owning cars or houses. And this makes sense: The general presumption is that you can privately own anything, with rare exceptions for items such as dangerous weapons or archaeological artifacts. The idea of controlling territory, specifically, has a long tenure. Animals, warlords, and governments all do it, and the modern conception of “fee simple”—that is, unrestricted, perpetual, and private—land ownership has existed in English common law since the 13th century.

Yet by 1797, US founding father Thomas Paine was arguing that “the earth, in its natural uncultivated state” would always be “the common property of the human race,” and so landowners owed non-landowners compensation “for the loss of his or her natural inheritance.”

A century later, economist Henry George saw that poverty was rising despite increasing wealth and blamed this on our system of owning land. He proposed that land should be taxed at up to 100 percent of its “unimproved” value—we’ll get to that in a moment—allowing other forms of taxes (certainly including property taxes, but also potentially income taxes) to be reduced or abolished. George became a sensation. His book Progress and Poverty sold 2 million copies, and he got 31 percent of the vote in the 1886 New York mayoral race (finishing second, narrowly ahead of a 31-year-old Teddy Roosevelt).

Read the rest of this article at: Wired