The Haves and the Have-Yachts

In the Victorian era, it was said that the length of a man’s boat, in feet, should match his age, in years. The Victorians would have had some questions at the fortieth annual Palm Beach International Boat Show, which convened this March on Florida’s Gold Coast. A typical offering: a two-hundred-and-three-foot superyacht named Sea Owl, selling secondhand for ninety million dollars. The owner, Robert Mercer, the hedge-fund tycoon and Republican donor, was throwing in furniture and accessories, including several auxiliary boats, a Steinway piano, a variety of frescoes, and a security system that requires fingerprint recognition. Nevertheless, Mercer’s package was a modest one; the largest superyachts are more than five hundred feet, on a scale with naval destroyers, and cost six or seven times what he was asking.

For the small, tight-lipped community around the world’s biggest yachts, the Palm Beach show has the promising air of spring training. On the cusp of the summer season, it affords brokers and builders and owners (or attendants from their family offices) a chance to huddle over the latest merchandise and to gather intelligence: Who’s getting in? Who’s getting out? And, most pressingly, who’s ogling a bigger boat?

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

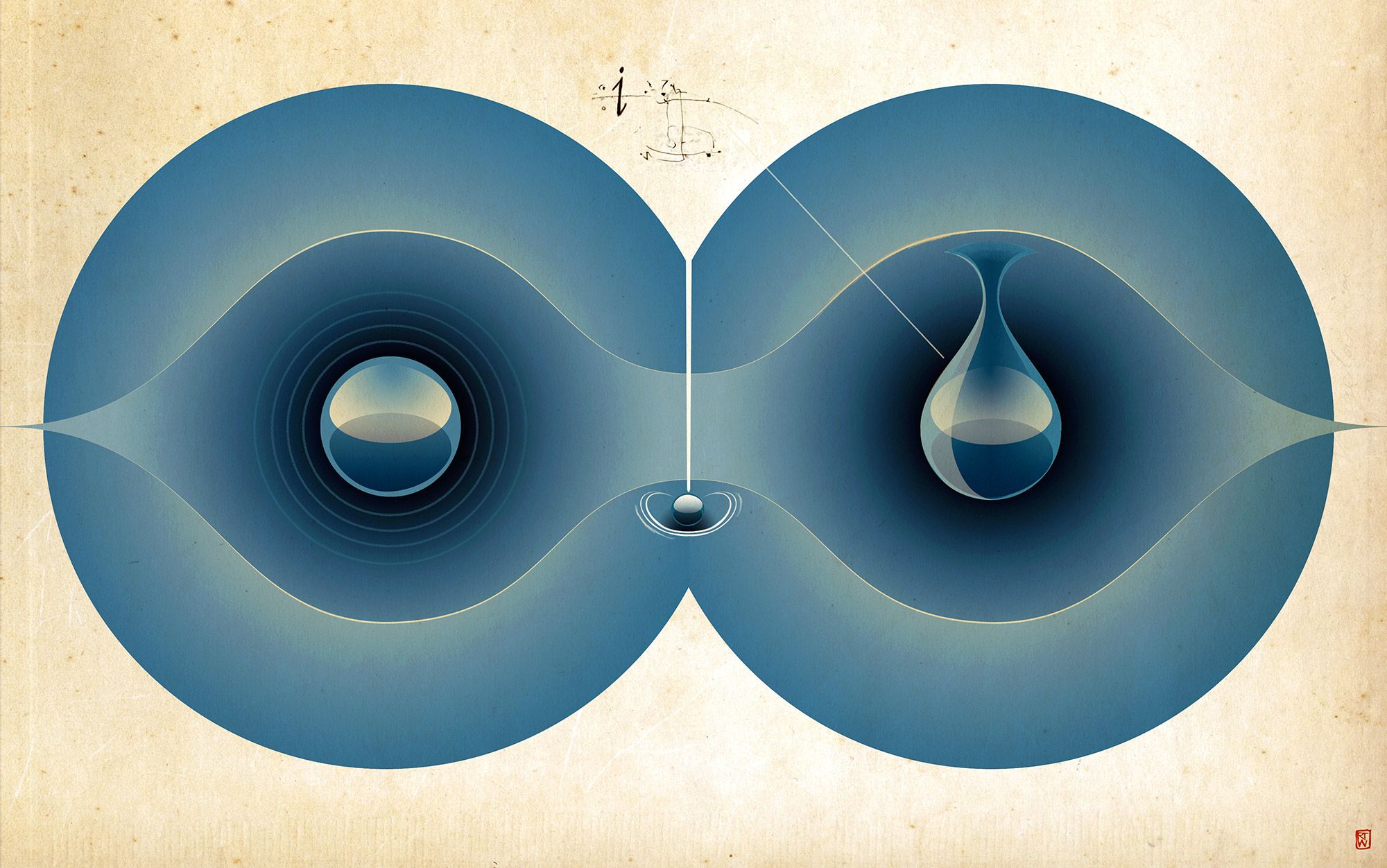

Many science students may imagine a ball rolling down a hill or a car skidding because of friction as prototypical examples of the systems physicists care about. But much of modern physics consists of searching for objects and phenomena that are virtually invisible: the tiny electrons of quantum physics and the particles hidden within strange metals of materials science along with their highly energetic counterparts that only exist briefly within giant particle colliders.

In their quest to grasp these hidden building blocks of reality scientists have looked to mathematical theories and formalism. Ideally, an unexpected experimental observation leads a physicist to a new mathematical theory, and then mathematical work on said theory leads them to new experiments and new observations. Some part of this process inevitably happens in the physicist’s mind, where symbols and numbers help make invisible theoretical ideas visible in the tangible, measurable physical world.

Sometimes, however, as in the case of imaginary numbers – that is, numbers with negative square values – mathematics manages to stay ahead of experiments for a long time. Though imaginary numbers have been integral to quantum theory since its very beginnings in the 1920s, scientists have only recently been able to find their physical signatures in experiments and empirically prove their necessity.

In December of 2021 and January of 2022, two teams of physicists, one an international collaboration including researchers from the Institute for Quantum Optics and Quantum Information in Vienna and the Southern University of Science and Technology in China, and the other led by scientists at the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC), showed that a version of quantum mechanics devoid of imaginary numbers leads to a faulty description of nature. A month earlier, researchers at the University of California, Santa Barbara reconstructed a quantum wave function, another quantity that cannot be fully described by real numbers, from experimental data. In either case, physicists cajoled the very real world they study to reveal properties once so invisible as to be dubbed imaginary.

For most people the idea of a number has an association with counting. The number five may remind someone of fingers on their hand, which children often use as a counting aid, while 12 may make you think of buying eggs. For decades, scientists have held that some animals use numbers as well, exactly because many species, such as chimpanzees or dolphins, perform well in experiments that require them to count.

Read the rest of this article at: aeon

This spring, a polling company surveyed Brits to find the nation’s most beloved exports. Beating out William Shakespeare and afternoon tea for the top three spots were the Sunday roast dinner, fish and chips, and the naturalist and television presenter Sir David Attenborough. A few years earlier, Attenborough, now ninety-six years old, was voted the most popular person in Britain. His popularity extends beyond national borders, too. The Australian comedian Ben Ellwood hosts a podcast called Thank God for David Attenborough, on which biologists join him to digest and appreciate episodes of Attenborough’s nature documentaries. But the metric of popularity that might matter most to Attenborough himself—one he has called “the biggest of compliments”—comes from the world of wildlife biology: dozens of species of plants and animals, living and extinct, including a bright blue and yellow lizard, a deep-water fish parasite, and a small golden wildflower, have been named after him.

Part of the reason that Attenborough is so beloved is simply the strength of his public-broadcasting version of star quality, a magic of affect and appearance. His accent is posh and plummy, his voice at once soft and authoritative as he describes the arrival of heavy clouds over a parched savannah or the rare midnight opening of some dusky bloom. Attenborough’s popularity has seemed to spike in recent years, in parallel with public understanding of the urgency of the climate crisis. Whether or not you consider yourself a “nature lover,” your media diet in recent years has most likely become saturated with stories of social and environmental peril driven by climate collapse. As wilderness disappears and our ways of experiencing it grow ever more mediated, Attenborough is there on the ground, pushing aside a branch to reveal some creature—or, as in his new series, Green Planet, which focuses on the lives of plants, zooming in on something special about the branch itself—and meeting the natural world with attention and reverence.

Read the rest of this article at: Dissent

The salvage yard at M. Maselli & Sons, in Petaluma, California, is made up of six acres of angle irons, block pulleys, doorplates, digging tools, motors, fencing, tubing, reels, spools, and rusted machinery. To the untrained eye, the place is a testament to the enduring power of American detritus, but to Foley artists—craftspeople who create custom sound effects for film, television, and video games—it’s a trove of potential props. On a recent morning, Shelley Roden and John Roesch, Foley artists who work at Skywalker Sound, the postproduction audio division of Lucasfilm, stood in the parking lot, considering the sonic properties of an enormous industrial hopper. “I’m looking for a resonator, and I need more ka-chunkers,” Roden, who is blond and in her late forties, said. A lazy Susan was also on the checklist—something to produce a smooth, swivelling sound. Roesch, a puffer-clad sexagenarian with white hair, had brought his truck, in the event of a large haul. The pair was joined by Scott Curtis, their Foley mixer, a bearded fiftysomething. Curtis was in the market for a squeaky hinge. “There was a door at the Paramount stage that had the best creak,” he said. “The funny thing was, the cleaning crew discovered this hinge squeak, and they lubricated the squeak—the hinge. It was never the same.”

Petaluma is a historically agricultural town, and that afternoon was the thirty-ninth annual Butter and Egg Days Parade; the air smelled of lavender and barbecued meat. Inside the yard, Curtis immediately gravitated toward a pile of what looked like millstones, or sanding wheels. He began rotating one against another, producing a gritty, high-pitched ring, like an elementary-school fire alarm. “The texture is great,” Roden said. She suggested that one of the wheels could be used as a sweetener—a sound that is subtly layered over another sound, to add dimension—for a high-tech roll-up door, or perhaps one made of stone. “It’s kinda chimey,” she said, wavering. “It has potential.” A few yards away, Curtis had moved on to a shelf of metal filing-cabinet drawers, freckled with rust. “We have so many metal boxes,” Roden said, and walked away.

“It’s kinda the squeak I was looking for,” Curtis said softly.

“Hey, guys, remember the ‘Black Panther’ area?” Roden called out. “Wanna explore?” She led the group past a rack of hanging chains, also rusted; Curtis lightly palmed a few in sequence, producing the pleasant rings of a tintinnabulum. Roden pointed to the spot where she had found a curved crowbar to create the sound of Vibranium—a fictional rare metal unique to the Marvel universe—before zeroing in on a rack of thimbles, clamps, nuts, bolts, and washers. The trio began knocking and tapping hardware together, producing a series of chimes, tinks, and clunks. Roesch, who calls himself an “audile”—someone who processes information in a primarily auditory manner, rather than in a visual or a material one—had unearthed a sceptre-like industrial tool with a moving part, and was rapidly sliding it back and forth. “Robot,” he said.

Read the rest of this article at: The Guardian

Victoria, Seychelles

When Olivier Bancoult boarded the ship that was to take him 1,000 miles across the Indian Ocean to the Chagos Archipelago—his childhood home, from which he and his fellow islanders had been expelled 50 years earlier—he carried five wrought-iron crosses. Most of them bore a short inscription, hand-lettered in white paint, memorializing the return of Chagossians to their birthplace. The crosses were to be driven into the ground of Peros Banhos and Salomon, two of the archipelago’s once-inhabited atolls. But one cross was different. It was inscribed with the name of Bancoult’s grandfather Alfred Olivier Elysé, and it was destined for an island cemetery. Elysé had died in 1969, as expulsions from the archipelago were under way.

The expulsions were part of an international bargain, though not one that the 2,000 people of Chagos had any say in. The short version: For many years, the archipelago was a faraway administrative appendage of the British colony of Mauritius, an island off the coast of Africa. When Mauritius sought independence, in the mid-1960s, Britain decided to keep Chagos for itself. It did so primarily to sequester one of the atolls, Diego Garcia, for use by the United States—part of a global American ambition, at the height of the Cold War, to establish military outposts in strategic places. Chagos itself was nowhere, but it was equidistant from everywhere: Draw a long line from Madagascar to Indonesia, and another from India to Antarctica, and stick a pin in the blue at the intersection. The catch for Britain was that under international law, the archipelago could be separated from Mauritius only if it had no “permanent population.”

Chagos did have a permanent population—it had had one for centuries. The Chagossians harvested coconuts and they fished. They had churches of stone. Mossy gravestones go back many generations. But a world away, in the offices of Whitehall and the clubs of St. James’s, this was a technicality. That the islanders involved were Black made decisions even easier. The conversations might reasonably be imagined, but they don’t have to be. Foreign and Colonial Office documents from the period state that, for official purposes, people living in Chagos were to be referred to as transitory “contract laborers.” The archipelago was described as having “no indigenous population except seagulls.” Internal documents freely admitted that all of this was a “fiction.” A few years before Alfred Olivier Elysé was laid to rest in the Catholic cemetery on Île du Coin, one of the Chagos islands, a comment scrawled on a British document by an official named Denis Greenhill captured the government’s outlook: “Along with the Birds go some few Tarzans or Men Fridays whose origins are obscure.”

One thing at least was true: Governmental fiat had the power to turn fable into fact. For reasons of state, the permanent inhabitants of the archipelago were removed, often with little warning, and typically allowed to bring only a single bag or suitcase or wooden box. The United States, which wanted and endorsed the expulsions, built its military base. The archipelago as a whole—Diego Garcia and some 60 other islands, mainly in the Peros Banhos and Salomon atolls—was reconstituted into a colonial entity known as the British Indian Ocean Territory, within which Diego Garcia could nest. Having been detached from Mauritius, BIOT would become both the newest British colony in Africa and the last remaining one.

Uprooted and desperately poor, the Chagossians formed small communities in Mauritius, the Seychelles, and the United Kingdom, with little support from any of those countries. As a remembrance, many kept sand from Chagos in small bowls in their home. On the balance scale of Cold War morality, the sand didn’t count for much. But the Chagossians never forgot where they’d come from—or, given that half a century has now elapsed, where their parents and grandparents had come from. Some hoped to return to Chagos, or at least to have that right. Some wanted a path to citizenship in Britain. Most wanted compensation commensurate with their loss.

Read the rest of this article at: The Atlantic

/media/cinemagraph/2022/06/09/WEL_Murphy_Chagos.mp4)