Sposato patented his diamond-shaped core, which he claims produces 20 percent more inertia than any competitor, and placed it in balls that he manufactured under the brand name Lane #1. But while he’s adamant that his core is the most advanced on the market, Sposato has always lagged behind Pinel in terms of sales and recognition. That dynamic led to years of conflict between the two ornery men. After one tussle in the online forum Bowling Ball Exchange, Pinel was banned for his caustic replies to Sposato’s criticism.

“See, Mo, he talks above everybody, talks down to people,” Sposato says. “People can’t understand what he’s talking about—physics-wise, all these big words, stuff like that. So they just look at him and they agree with him. But I can see right through it. I know what he’s talking about, what he’s saying, and I can always throw it right back in his face.” (In addition to designing Lane #1 balls, Sposato also owns a nightclub in Syracuse; he made headlines last year for openly flouting the state’s lockdown by hosting a party.)

Read the rest of this article at: Wired

Last June, when most Americans could agree that their country was in crisis but few could agree on what to do about it, staffers from a small organization called Justice Democrats—part of a burgeoning faction of young activists whose goal is to push the Democratic Party, and thus the entire political spectrum, to the left—joined a gathering on the patio of a restaurant in Yonkers, overlooking the Hudson. It was a breezy Tuesday night, and polls in the congressional primary had just closed. Most of the staffers hadn’t seen one another in person since COVID lockdowns began, and their hesitant enthusiasm—distant air hugs, cocktails sipped hastily between remaskings—seemed appropriate to the event, which could, at any moment, turn into either a victory party or a defeat vigil. A lectern, framed by string lights and uplit pine trees, stood empty, apart from a sign bearing their candidate’s name: Jamaal Bowman. Bowman was still out campaigning, urging voters at crowded polls to stay in line. At least, that’s what everyone assumed. He had no staff with him, and his phone was dead.

Bowman was running to replace Eliot Engel, who represented southern Westchester and the North Bronx in Congress. Since being elected, in 1988, Engel had breezed through fifteen reëlection campaigns, usually without serious competition. But he was a seventy-three-year-old white man whose constituents were relatively young and racially diverse. He was also a moderate Democrat—militarily and monetarily hawkish, and a recipient of numerous corporate donations—in an increasingly progressive district. Seeing an opportunity, Justice Democrats had encouraged Bowman, a middle-school principal in his forties and an avid supporter of the Black Lives Matter and environmental-justice movements, to run a long-shot primary campaign against Engel. “I identify as an educator and as a Black man in America,” he said in a video interview with the Intercept. “But my policies align with those of a socialist”—grin, shrug—“so I guess that makes me a socialist.”

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

Levi Jed Murphy smoulders into the camera. It’s a powerful look: piercing blue eyes, high cheekbones, full lips and a razor-sharp jawline – all of which, he says, cost him around £30,000. Murphy is an influencer from Manchester in the UK, with a large social media following. Speaking on his approach to growing his fans, he says that, if a picture doesn’t receive a certain number of ‘Likes’ within a set time, it gets deleted. His surgeries are simply a way to achieve rapid validation: ‘Being good-looking is important for … social media, because obviously I want to attract an audience,’ he says.

His relationship with social media is a striking manifestation of the worries expressed by the French philosopher Guy Debord, in his classic work The Society of the Spectacle (1967). Social life is shifting from ‘having to appearing – all “having” must now derive its immediate prestige and its ultimate purpose from appearances,’ he claims. ‘At the same time all individual reality has become social.’ Debord recognised that individuals were increasingly beset by social forces, a prescient observation in light of the later rise of social media. But as a political theorist writing in the 1960s, Debord would have struggled to see how this shift towards appearances could affect human psychology and wellbeing, and why people such as Murphy might feel the need to take drastic action.

Read the rest of this article at: aeon

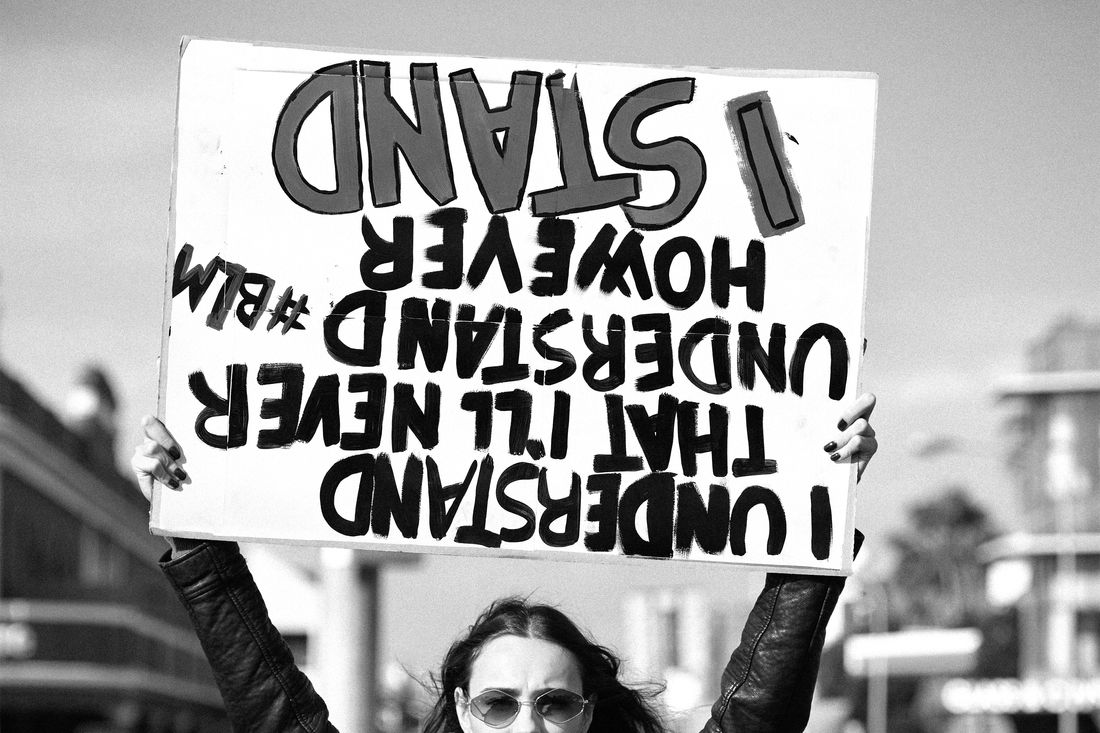

“Man Dies After Medical Incident During Police Interaction” was the title of the initial statement the Minneapolis Police Department released after Officer Derek Chauvin killed George Floyd a year ago. It explained: “He was ordered to step from his car. After he got out, he physically resisted officers. Officers were able to get the suspect into handcuffs and noted he appeared to be suffering medical distress.”

The narrative was untrue in both broad outlines and specific details, muddying cause and effect, subject and object. We know because of cell phone video recorded by Darnella Frazier, then 17 years old, that revealed what really happened.

“At no time were weapons of any type used by anyone involved in this incident,” the statement read. Frazier’s video showed how Chauvin killed Floyd. He weaponized his body by kneeling on Floyd’s neck for over eight minutes, ignoring Floyd’s pleas for air, causing the “medical distress,” committing murder.

In statements like this one, police stretch, manipulate, and abuse plain language. Across the United States, in the most heavily policed neighborhoods, and as recorded on protest placards or in innumerable rap, reggae, and punk lyrics, it’s widely understood, if not accepted, that cops lie.

Reading police literature gives you a diametrically opposed account. You learn that police are locally accountable, domestically oriented, civilian peacekeepers. They are politically nonpartisan and neutral enforcers of the law, guided by policy, science, and rank discipline. John Elder, the director of public information for the Minneapolis Police Department and author of the Floyd statement, called its falsehoods a consequence of a “fluid” situation. A cop would never lie. “We try very hard to get information out as quickly as possible that is wholly honest and correct,” he told the Star Tribune. “There is no way I’m going to lie about a situation that is on body camera and is going to prove this department to be disingenuous.” The message is that police prevent violence, investigate and solve crime mysteries, and answer to a mass public demanding that they accomplish these tasks with alacrity.

You could call these the sustaining myths of policing, but I think of them as political arguments police make. They are instrumental, a means toward an end. Police attempt to achieve legitimacy through the stories they tell about themselves. Police legitimacy means public compliance. It means power.

It’s thus not simply that cops mislead in their statements to the press after an “officer-involved shooting.” The lie that police tell is not only rendered in deceptive language. It’s not about the words they choose. The lie is baked into the institution. The core of policing is not safety. It is social control. All the other lies obfuscate this function.

Read the rest of this article at: The New Republic

Follow us on Instagram @thisisglamorous

[instagram-feed]

When, before the pandemic, I started getting into bourbon, I wanted to learn everything about it — what it was made of, how it was created, how to find the best bottles. I watched whiskey-review channels on YouTube and read bourbon blogs and history books, which is to say I spent a lot of time listening to and reading about white people.

It’s not that Black people have had no hand in shaping the bourbon industry — nothing has happened in this country without Black people’s contributions, be it through forced labor and exploitation or appropriation. Some historians, like Kansas State University’s Dr. Erin Wiggins Gilliam, have found evidence that enslaved Africans even worked as distillers, rented out by slave owners to Kentucky distilleries. But Black people make up only 9 percent of bourbon drinkers, which likely has something to do with the way bourbon has been marketed. At the turn of the 20th century, some distilleries used minstrel imagery in their advertisements, and since then, bourbon has retained its associations with a particular brand of white southern masculinity.

I like bourbon because of the flavors — caramel, brown sugar, and vanilla — and it excites me to tease out differences between styles that have more fruit-forward tastes or notes of baking spices. But I dislike the culture surrounding it, and not solely because it is so white — rather, because there is so little acknowledgment of its whiteness. I have spent hours watching YouTube bourbon personalities sound off on mash bills and barrels without ever wondering aloud why the communities they have created look so much like themselves. I’ve only seen one video from one white creator attempt to address this; it is one of his least popular.

So when, last summer, the issuance of an anti-racist statement became a perfunctory obligation of major U.S. companies, I wasn’t expecting any response from the bourbon industry. I figured its consumers so heavily skewed toward the type of people who brandish BLUE LIVES MATTER flags that bourbon-makers would view it as unnecessary or even unwise to comment on the nation’s racial unrest.

I was wrong. Nearly every major distillery, and even some smaller distilleries, made statements condemning racism and claiming solidarity with Black communities. Wild Turkey’s parent company pledged $300,000 to the Equal Justice Initiative, while Jim Beam said it would donate $150,000 to “support Black-owned restaurants and bars.” I’m not surprised by much when it comes to American racism, but this managed a “Huh, interesting” out of me.

I say nearly every major distillery because there was one holdout: Buffalo Trace. It is home to some of the most-sought-after bourbons on the market, including the famed Pappy Van Winkle, but the reason the company’s silence stood out — not even a solid black square on Instagram or hashtag Black Lives Matter on an innocuous landscape image — is because it is the only bourbon brand with a Black person serving as a public face. Freddie Johnson is a third-generation employee at Buffalo Trace and a distillery tour guide of some renown. His name and face are on Buffalo Trace’s soda brand. But the company wouldn’t even say publicly that it thinks racism is bad.

Read the rest of this article at: The Cut