Earlier this year, two men launched a podcast made up of meandering conversations about their friendship and the state of the world. Nothing unusual there. Of the two million or so podcast series in existence (that’s 48m episodes and counting), a large proportion is made up of groups of men talking about themselves and laughing at their own jokes. The difference in this instance was that the friends were Barack Obama and Bruce Springsteen. In launching the Spotify series Renegades, they brought together two distinctive audio trends: the old-friends-chew-the-fat series, and the now-ubiquitous celebrity podcast.

The celebrity series has been a growth area for some time, but the last 12 months have brought a surge in projects from famouses who have found themselves at a loose end over lockdown. While much of the entertainment industry has been devastated by the pandemic, podcasting has proved largely virus-proof, making it an attractive proposition to those who, a year earlier, might not have given it a second look. As a result, the celebrity podcast has become the bindweed of the audio industry, hoovering up budgets, threatening to smother the competition and, in some cases, heralding a dispiriting drop in quality.

Read the rest of this article at: The Guardian

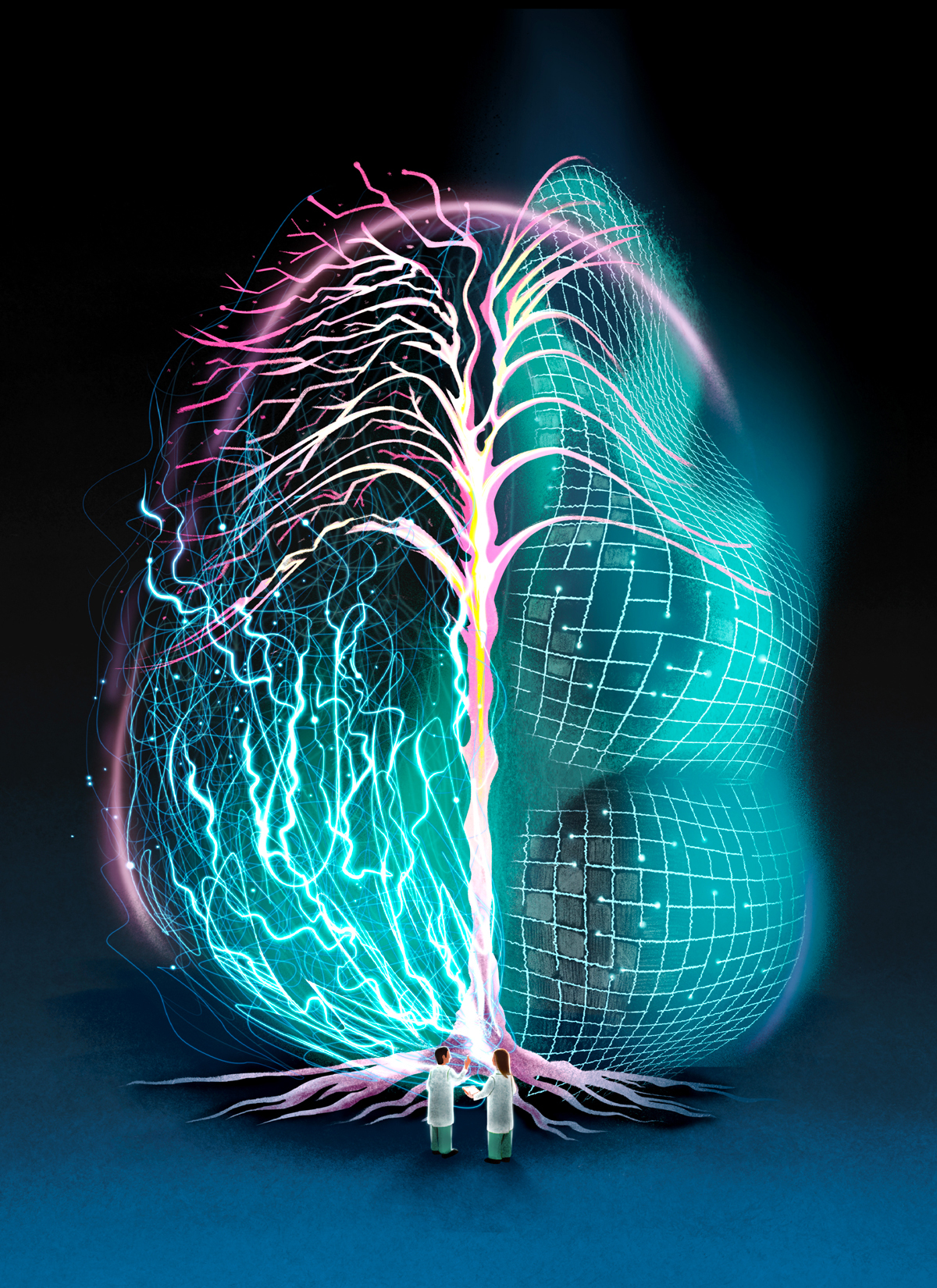

In the ’90s, when he was a doctoral student at the University of Lausanne, in Switzerland, neuroscientist Sean Hill spent five years studying how cat brains respond to noise. At the time, researchers knew that two regions—the cerebral cortex, which is the outer layer of the brain, and the thalamus, a nut-like structure near the centre—did most of the work. But, when an auditory signal entered the brain through the ear, what happened, specifically? Which parts of the cortex and thalamus did the signal travel to? And in what order? The answers to such questions could help doctors treat hearing loss in humans. So, to learn more, Hill, along with his supervisor and a group of lab techs, anaesthetized cats and inserted electrodes into their brains to monitor what happened when the animals were exposed to sounds, which were piped into their ears via miniature headphones. Hill’s probe then captured the brain signals the noises generated.

The last step was to euthanize the cats and dissect their brains, which was the only way for Hill to verify where he’d put his probes. It was not a part of the study he enjoyed. He’d grown up on a family farm in Maine and had developed a reverence for all sentient life. As an undergraduate student in New Hampshire, he’d experimented on pond snails, but only after ensuring that each was properly anaesthetized. “I particularly loved cats,” he says, “but I also deeply believed in the need for animal data.” (For obvious reasons, neuroscientists cannot euthanize and dissect human subjects.)

Over time, Hill came to wonder if his data was being put to the best possible use. In his cat experiments, he generated reels of magnetic tape—printouts that resembled player piano scrolls. Once he had finished analyzing the tapes, he would pack them up and store them in a basement. “It was just so tangible,” he says. “You’d see all these data coming from the animals, but then what would happen with it? There were boxes and boxes that, in all likelihood, would never be looked at again.” Most researchers wouldn’t even know where to find them.

Read the rest of this article at: The Walrus

In 1991, with America gripped by a struggle between an increasingly liberal secular society that pushed for change and a conservative opposition that rooted its worldview in divine scripture, James Davison Hunter wrote a book and titled it with a phrase for what he saw playing out in America’s fights over abortion, gay rights, religion in public schools and the like: “Culture Wars.”

Hunter, a 30-something sociologist at the University of Virginia, didn’t invent the term, but his book vaulted it into the public conversation, and within a few years it was being used as shorthand for cultural flashpoints with political ramifications. He hoped that by calling attention to the dynamic, he’d help America “come to terms with the unfolding conflict” and, perhaps, defuse some of the tensions he saw bubbling.

Instead, 30 years later, Hunter sees America as having doubled down on the “war” part—with the culture wars expanding from issues of religion and family culture to take over politics almost totally, creating a dangerous sense of winner-take-all conflict over the future of the country.

“Democracy, in my view, is an agreement that we will not kill each other over our differences, but instead we’ll talk through those differences. And part of what’s troubling is that I’m beginning to see signs of the justification for violence,” says Hunter, noting the insurrection on January 6, when a mob of extremist supporters of Donald Trump stormed the U.S. Capitol in an attempt to overthrow the results of the 2020 election. “Culture wars always precede shooting wars. They don’t necessarily lead to a shooting war, but you never have a shooting war without a culture war prior to it, because culture provides the justifications for violence.”

What changed? In the latter half of the 20th century, the culture war was, on some level, a “cultural conflict that took place primarily within the white middle class,” says Hunter, who now leads the University of Virginia’s Institute for Advanced Studies in Culture. But, today, as that conflict has grown, “instead of just culture wars, there’s now a kind of class-culture conflict” that has moved beyond the simple boundaries of religiosity.

“The earlier culture war really was about secularization, and positions were tied to theologies and justified on the basis of theologies,” says Hunter. “That’s no longer the case. You rarely see people on the right rooting their positions within a biblical theology or ecclesiastical tradition. [Nowadays,] it is a position that is mainly rooted in fear of extinction.”

In 1991, politics still seemed like a vehicle through which we might resolve divisive cultural issues; now, politics is primarily fueled by division on those issues, with leaders gaining power by inflaming resentments on mask-wearing, or transgender students competing in athletics, or invocations of “cancel culture,” or whether it’s OK to teach that many of the Founding Fathers had racist beliefs. And this reality—that the culture war has colonized American politics—is troubling precisely because of an observation Hunter made in 1991 about the difference he saw between political issues and culture war fights: “On political matters, one can compromise; on matters of ultimate moral truth, one cannot.”

Where does that leave us? What does it portend for the decades to come? Is there a way to bridge these cultural impasses? And, amid all of this, is there a source for optimism?

Read the rest of this article at: Politico

Sky Lane scrolled through the pictures from an impromptu photo shoot she’d done with her friend and picked her favorite. It was cute — she was showing off her side profile in a black crop top, tight blue jeans, big silver hoops and smoky bronze eyeshadow. But the 21-year-old wouldn’t dare post it to Instagram for the world to see just yet. She opened Facetune, a photo-retouching app on her iPhone, and got to work.

Using the “Reshape” tool, she started pushing her tummy inward, little by little. She had to be careful not to noticeably warp the background in the process; the trick was to edit the photo without making it look like it had been edited. Skewed lines, blurry edges and inconsistencies in shadows and reflections were easy giveaways that Lane had learned how to avoid through years of practice — she’d been Facetuning since she was a teenager. She used the same tool to give herself a breast lift, slim her arm, cinch her waist and make her butt rounder, like the bodies flooding her Instagram feed.

Next she moved onto her face. Her friend had taken the photo using a Snapchat filter that had already plumped her lips, slimmed her nose and smoothed her skin so much her pores were no longer visible, but Lane applied Facetune’s complexion retouching effect for good measure. Her jawline was an easy fix with the jaw-slimming tool. Usually she’d whiten her teeth, but they were hardly showing. The more technical tweaks, like individually repositioning her eyebrows and narrowing the tip of her nose, required tools only available on the paid version of the app, which she’d upgraded to long ago.

She was done in under 20 minutes. The final product still looked like her, Lane decided, just a better, more acceptable version. She sent it to her mom, who didn’t seem to notice that anything had been altered, giving Lane the reassurance she needed that it was pretty and believable — polished but not overdone. She wouldn’t want her followers to accuse her of being a “catfish,” a term that has evolved in the Facetune era to describe someone who enhances their pictures beyond recognition.

Lane was finally ready to post the photo. It got 179 “likes,” which she thought was pretty good; without Facetune, she figured, she’d be lucky to get 40. Like the myriad other women who’ve been conditioned to pick apart their appearances, Lane has countless insecurities — including many that are invisible to everyone except her. The app makes them go away with a few simple finger strokes and ushers in the social validation she craves, which is at once addictively thrilling and utterly depressing.

Facetune makes it harder for her to love herself, but at least she can love her selfie.

“It can get super obsessive, because the second I take a photo I feel like I need to Facetune it,” Lane said. “Now I’ll be like, ‘Oh my God, I’m chubby, but I can fix that.’”

Photo-retouching technology has existed for decades, and concern about its toll on the self-esteem of women, and girls in particular, is nothing new. But with the meteoric rise of Facetune and a suite of similar apps that put ever-advancing versions of these tools into the pocket of anyone with a smartphone, digitally perfected faces and bodies are no longer restricted to magazine covers or pictures posted by celebrities who can afford cosmetic surgeries and professional photo editors.They’re everywhere in our social media world: all over the profiles of influencers and, quite possibly, your own friends. As a result, the pressure facing today’s young women to look flawless can feel inescapable.

We’ve been sinking deeper into this reality for a while now, but it has accelerated during the pandemic, when we’ve spent more time than ever on social media, and when our digital selves have for so long been the only version anyone has seen of us. The result is a body dysmorphia epidemic with increasingly unattainable beauty standards that — at the extremes — defy basic human physiology.

Read the rest of this article at: Huffpost