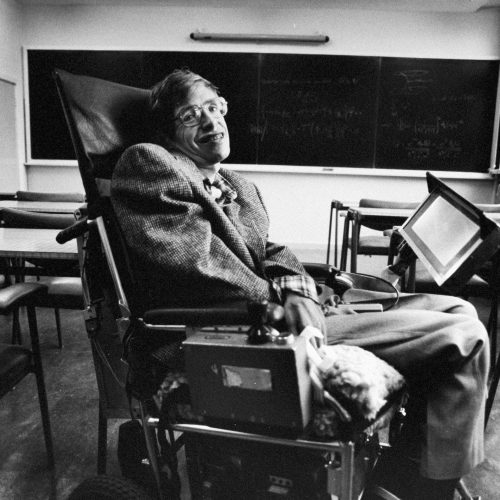

Stephen Hawking Dies at 76; His Mind Roamed the Cosmos

Stephen W. Hawking, the Cambridge University physicist and best-selling author who roamed the cosmos from a wheelchair, pondering the nature of gravity and the origin of the universe and becoming an emblem of human determination and curiosity, died early Wednesday at his home in Cambridge, England. He was 76.

A university spokesman confirmed the death.

“Not since Albert Einstein has a scientist so captured the public imagination and endeared himself to tens of millions of people around the world,” Michio Kaku, a professor of theoretical physics at the City University of New York, said in an interview.

Dr. Hawking did that largely through his book “A Brief History of Time: From the Big Bang to Black Holes,” published in 1988. It has sold more than 10 million copies and inspired a documentary film by Errol Morris. His own story was the basis of an award-winning 2014 feature film, “The Theory of Everything.” (Eddie Redmayne played Dr. Hawking and won an Academy Award.)

Read the rest of this article at: The New York Times

Does Recovery Kill Great Writing?

The first time I felt it — the buzz — I was almost 13. I didn’t vomit or black out or even embarrass myself. I just loved it. I loved the crackle of Champagne, its hot pine needles down my throat. We were celebrating my brother’s college graduation, and I wore a long muslin dress that made me feel like a child, until I felt something else: initiated, aglow. The whole world stood accused: You never told me it felt this good.

The first time I drank in secret, I was 15. My mom was out of town. My friends and I spread a blanket across the living-room hardwood and drank whatever we could find in the fridge, the chardonnay wedged between the orange juice and the mayonnaise. We were giddy from the sense of trespass.

The first time I got high, I was smoking pot on a stranger’s couch, dampening the joint between fingers dripping with pool water. A friend of a friend had invited me to a swimming party. My hair smelled like chlorine, and my body quivered against my damp bikini. Strange little animals blossomed through my elbows and shoulders, where the parts of me bent and connected. I thought: What is this? And how can it keep being this? With a good feeling, it was always: More. Again. Forever.

The first time I drank with a boy, I let him put his hands under my shirt on the wooden balcony of a lifeguard station. Dark waves shushed the sand below our dangling feet. My first boyfriend: He liked to get high. He liked to get his cat high. We used to make out in his mother’s minivan. He came to a family meal at my house fully wired on speed. “So talkative!” said my grandma, deeply smitten. At Disneyland, he broke open a baggie of withered mushroom caps and started breathing fast and shallow in line for Big Thunder Mountain Railroad, sweating through his shirt, pawing at the orange rocks of the fake frontier.

If I had to say where my drinking began — which first time began it — I might say it started with my first blackout, or maybe the first time I sought blackout: the first time I wanted nothing more than to be absent from my own life. Maybe it started the first time I threw up from drinking; the first time I dreamed about drinking; the first time I lied about drinking; the first time I dreamed about lying about drinking, when the craving had become so deep that there wasn’t much of me that wasn’t committed to either serving or fighting it.

I was afraid that loving the drunk story best meant some part of me still wanted to keep living it. And of course, some part of me did.

Read the rest of this article at: The New Tork Times Magazine

Shia LaBeouf Is Ready To Talk About It

Shia LaBeouf is nervous about this story—“I have so much fear about this thing,” he confesses to me when we first meet—and it drives him to do what he’s always done when faced with something he cannot fully control: Prepare. Obsessively. For the past two months, he’s conducted practice interviews over the phone with his therapist, anticipating all of the possible scenarios, workshopping his responses to my questions. It’s been a long time since Vanity Fair put him on the cover of its August 2007 issue, wearing a spacesuit over a suit-suit (it looks as awkward as it sounds), and heralded him at age twenty-one as “the Next Tom Hanks.” More than a decade on, LaBeouf’s arc is less a stratospheric ascent than a misguided rocket wobbling across the sky, strewing wreckage.

Yes, LaBeouf is the guy who was handed a golden ticket and promptly lit it on fire. But too often we forget that everyone screws up on their path toward becoming an adult; and that few do so under the gaze of the public eye; and that by embracing the kind of capital-A Acting LaBeouf aims to do, we nourish the same spark from which his bad behavior stems. Tom Hardy, who worked with LaBeouf on 2012’s Lawless, points to the paradox central to their work. “A performer is asked to do two things,” he tells me. “To be disciplined and accountable, communicative and a pleasure to work with. And then, within a split second, they’re asked to be a psychopath. Authentically. It takes a very strong human being to sustain a genuine sense of well-being through that baptism of fire.” Then: “Drama is not known to attract stable types.”

Read the rest of this article at: Esquire

Thus spake Albert

In late 2017, a sheet of paper bearing a 13-word sentence in German in the original handwriting of Albert Einstein went on sale at an auction house in Jerusalem. The city is home to the archives of Einstein, which he willed before his death in 1955 to the Hebrew University, the institution that he helped to found in the 1920s. The Albert Einstein Archives now contain some 30,000 documents. Several times the size of Galileo Galilei’s and Isaac Newton’s archives, they rival the archives of Napoleon Bonaparte. However, the provenance of this particular paper had nothing to do with the Archives, despite a copy of it being held in the collection. It was decidedly more intriguing.

The paper was inscribed and autographed in Japan on the stationery of the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo and dated November 1922, the month in which Einstein was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics. He stayed at this hotel during his massively popular lecture tour of Japan, when he attracted even more attention than the Japanese imperial family. Apparently somewhat embarrassed by such frenetic publicity, Einstein decided to record some of his thoughts and feelings about life in writing. He gave this particular sentence (and another shorter one) to a Japanese delivery courier, either because the courier refused to accept a tip, in keeping with local practice, or because Einstein had no small change. ‘Maybe if you’re lucky those notes will become much more valuable than just a regular tip,’ Einstein apparently told the unnamed Japanese courier, according to the document’s seller, reported by the BBC to be the courier’s nephew.

The Jerusalem auction house estimated that the note would sell for between $5,000 and $8,000. Bidding started at $2,000. For about 20 minutes, a flurry of offers pushed up the price rapidly, until the final two bidders vied for the trophy by telephone. By the end, the price had risen to a scarcely believable $1.56 million.

Translated into English, Einstein’s sentence reads: ‘A calm and modest life brings more happiness than the pursuit of success combined with constant restlessness.’

The absurdity of this auction would not have been lost on Einstein, were he still with us. During the second half of his life, following the British-led astronomical confirmation of his theory of general relativity in 1919, he was unfailingly puzzled by his celebrity and uninterested in amassing money for its own sake. He was happiest when left alone with his mathematical calculations or with a select handful of fellow physicists and mathematicians – in Zurich, Berlin, Oxford, Pasadena and Princeton. On the long sea journey from Europe to Japan and back, he loved to retreat into his cabin and scribble mathematical equations

Read the rest of this article at: aeon

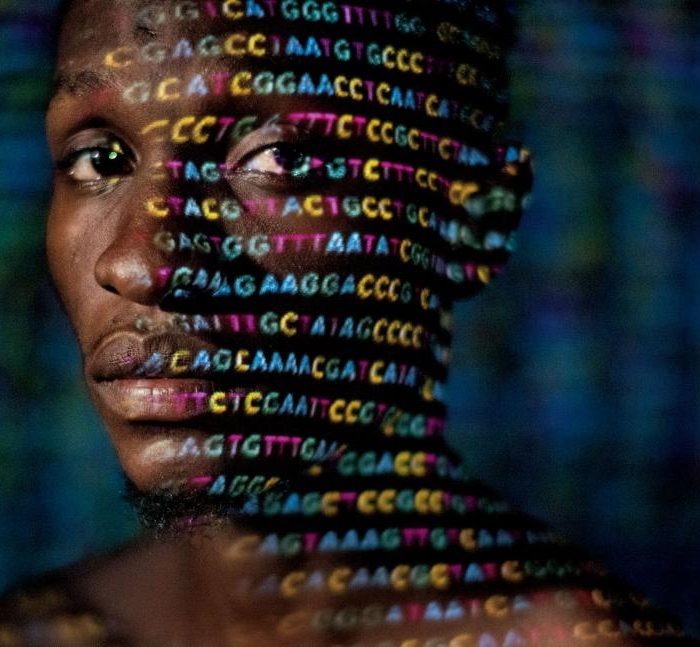

There’s No Scientific Basis for Race—It’s a Made-Up Label

In the first half of the 19th century, one of America’s most prominent scientists was a doctor named Samuel Morton. Morton lived in Philadelphia, and he collected skulls.

He wasn’t choosy about his suppliers. He accepted skulls scavenged from battlefields and snatched from catacombs. One of his most famous craniums belonged to an Irishman who’d been sent as a convict to Tasmania (and ultimately hanged for killing and eating other convicts). With each skull Morton performed the same procedure: He stuffed it with pepper seeds—later he switched to lead shot—which he then decanted to ascertain the volume of the braincase.

Morton believed that people could be divided into five races and that these represented separate acts of creation. The races had distinct characters, which corresponded to their place in a divinely determined hierarchy. Morton’s “craniometry” showed, he claimed, that whites, or “Caucasians,” were the most intelligent of the races. East Asians—Morton used the term “Mongolian”—though “ingenious” and “susceptible of cultivation,” were one step down. Next came Southeast Asians, followed by Native Americans. Blacks, or “Ethiopians,” were at the bottom. In the decades before the Civil War, Morton’s ideas were quickly taken up by the defenders of slavery.

This story helps launch a series about racial, ethnic, and religious groups and their changing roles in 21st-century life. The series runs through 2018 and will include coverage of Muslims, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Native Americans.

“He had a lot of influence, particularly in the South,” says Paul Wolff Mitchell, an anthropologist at the University of Pennsylvania who is showing me the skull collection, now housed at the Penn Museum. We’re standing over the braincase of a particularly large-headed Dutchman who helped inflate Morton’s estimate of Caucasian capacities. When Morton died, in 1851, the Charleston Medical Journal in South Carolina praised him for “giving to the negro his true position as an inferior race.”

Today Morton is known as the father of scientific racism. So many of the horrors of the past few centuries can be traced to the idea that one race is inferior to another that a tour of his collection is a haunting experience. To an uncomfortable degree we still live with Morton’s legacy: Racial distinctions continue to shape our politics, our neighborhoods, and our sense of self.

This is the case even though what science actually has to tell us about race is just the opposite of what Morton contended.

Morton thought he’d identified immutable and inherited differences among people, but at the time he was working—shortly before Charles Darwin put forth his theory of evolution and long before the discovery of DNA—scientists had no idea how traits were passed on. Researchers who have since looked at people at the genetic level now say that the whole category of race is misconceived. Indeed, when scientists set out to assemble the first complete human genome, which was a composite of several individuals, they deliberately gathered samples from people who self-identified as members of different races. In June 2000, when the results were announced at a White House ceremony, Craig Venter, a pioneer of DNA sequencing, observed, “The concept of race has no genetic or scientific basis.”

Over the past few decades, genetic research has revealed two deep truths about people. The first is that all humans are closely related—more closely related than all chimps, even though there are many more humans around today. Everyone has the same collection of genes, but with the exception of identical twins, everyone has slightly different versions of some of them. Studies of this genetic diversity have allowed scientists to reconstruct a kind of family tree of human populations. That has revealed the second deep truth: In a very real sense, all people alive today are Africans.

Read the rest of this article at: National Geographic

Follow us on Instagram @thisisglamorous

[instagram-feed]