UPDATE: It has been sadly reported that Karl Lagerfeld passed away in Paris this morning, on Tuesday February 19, 2019. He was 85. Lagerfeld, who was the creative director of French fashion brand Chanel since 1983, was unable to attend his label’s Paris Fashion Week show in January. He was admitted to the American Hospital in Paris on Monday, and passed away there the following morning according to local reports.

“Going to museums and looking at great art can help you write better songs. Reading great novels… Seeing a great movie… reading poetry… The more you can do to get out of the mode of competition, where you get out of what other people are doing and wanting to be better than them or be inspired by them. The only way to use the inspiration of other artists is if you submerge yourself in the greatest works of all time, which is a great thing to do. If you listen to the greatest songs ever made, that would be a better way to work through to find your own voice to matter today then listening to what’s on the radio now and thinking, ‘I want to compete with this.'” —Rick Rubin

In this new series we will be looking at what books, music and films have influenced successful artists, musicians, actors, directors and authors.

If you are, perhaps, searching for creative inspiration or looking to explore new ideas, we hope this series will act as a jumping off point for some new discoveries. —P.F.M.

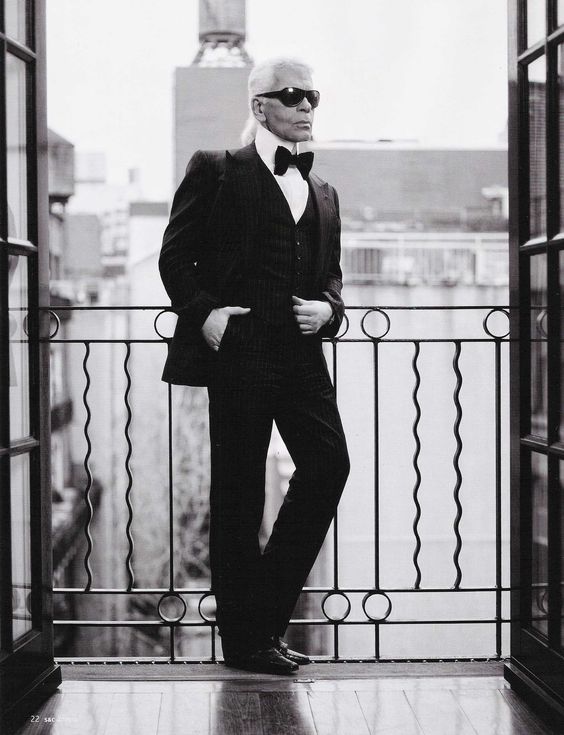

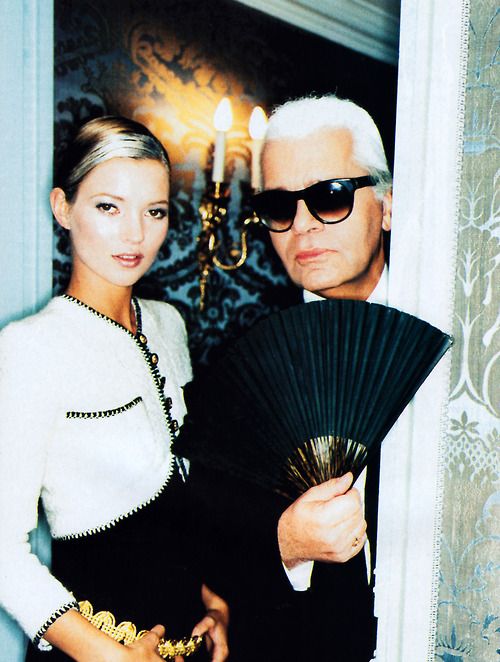

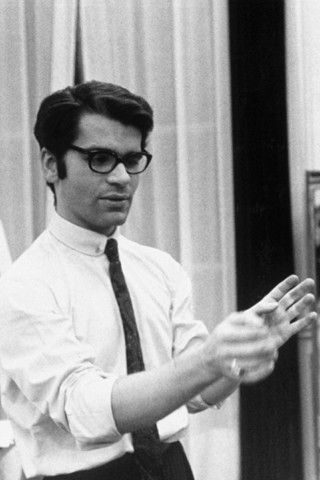

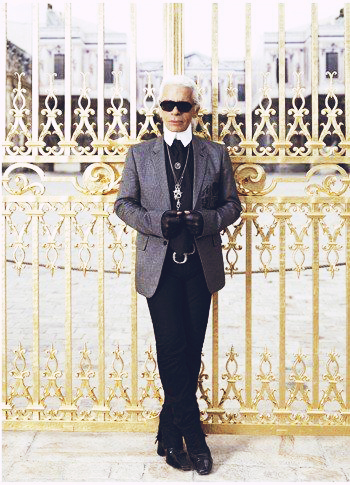

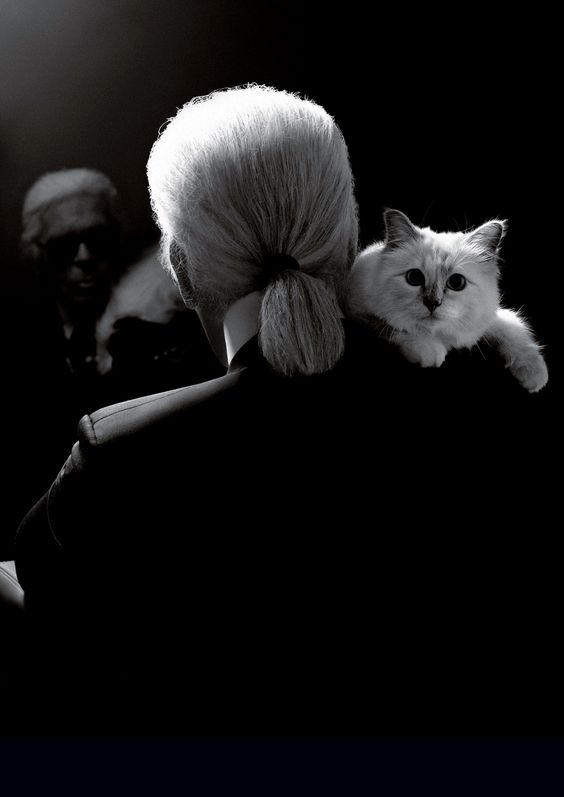

Last in the series we looked at David Bowie’s inspirations and influences. This week we will be looking at the fashion designer and icon Karl Lagerfeld. Lagerfeld’s illustrious career began in the 1950’s but he is perhaps best known for taking the helm of Chanel in the 1980’s and redefining the brand. Like Bowie, Lagerfeld is avid collector of art, music and books.

Favourite Books

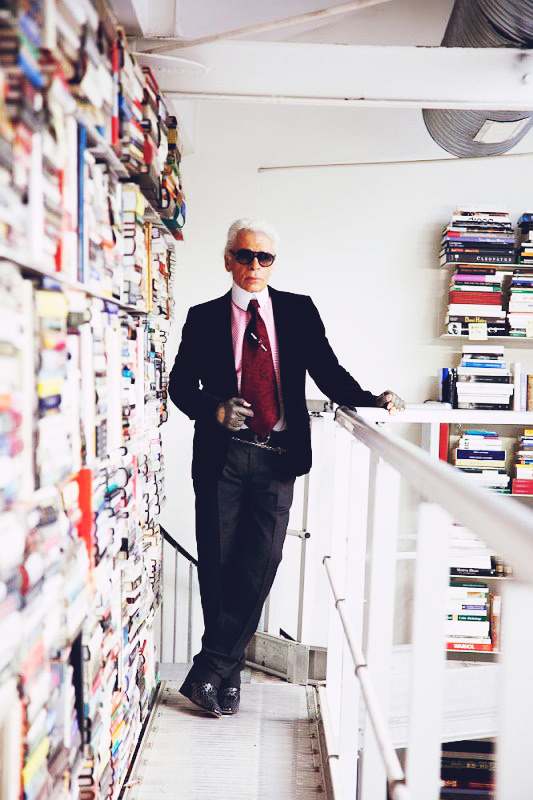

‘I first discovered books when I was five years old in my parents’ library, and I’ve been buying books my whole life. Emotional order doesn’t exist and I read in three languages, following no rules just my instinct.’ —Karl Lagerfeld

Karl Lagerfeld has a massive home library with a wide range of books from design to poetry and philosophy.

Below are a few selections of his favourites. See the full list at Vogue Paris

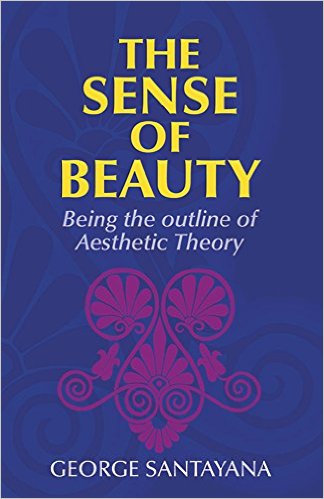

The Sense of Beauty: Being the Outline of Aesthetic Theory

This unabridged reproduction of the 1896 edition of lectures delivered at Harvard College is a study of “why, when, and how beauty appears, what conditions an object must fulfill to be beautiful, what elements of our nature make us sensible of beauty, and what the relation is between the constitution of the object and the excitement of our susceptibility.”

Spinoza: Complete Works

The only complete edition in English of Baruch Spinoza’s works, this volume features Samuel Shirley’s preeminent translations, distinguished at once by the lucidity and fluency with which they convey the flavor and meaning of Spinoza’s original texts.

Duino Elegies: Rainer Maria Rilke

Written in a period of spiritual crisis between 1912 and 1922, the poems that compose the Duino Elegies are the ones most frequently identified with the Rilkean sensibility. With their symbolic landscapes, prophetic proclamations, and unsettling intensity, these complex and haunting poems rank among the outstanding visionary works of the century.

The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson: Emily Dickinson

Though generally overlooked during her lifetime, Emily Dickinson’s poetry has achieved acclaim due to her experiments in prosody, her tragic vision and the range of her emotional and intellectual explorations.

The Iliad: Homer

Dating to the ninth century B.C., Homer’s timeless poem still vividly conveys the horror and heroism of men and gods wrestling with towering emotions and battling amidst devastation and destruction, as it moves inexorably to the wrenching, tragic conclusion of the Trojan War. Renowned classicist Bernard Knox observes in his superb introduction that although the violence of the Iliad is grim and relentless, it coexists with both images of civilized life and a poignant yearning for peace.

Elective Affinities: Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe

Condemned as immoral when it was first published, this novel reflects the conflict Goethe felt between his respect for the conventions of marriage and the possibility of spontaneous passion.

Karl Lagerfeld is a cinephile with an affinity for European art house cinema. Below are a few of our favourite selections. For a full listing of his favourite films, see Vogue Paris

Children of Paradise (1945)

Director: Marcel Carné

Writer: Jacques Prévert (scenario and dialogue)

Stars: Arletty, Jean-Louis Barrault, Pierre Brasseur

All discussions of Marcel Carne’s Children of Paradise begin with the miracle of its making. Named at Cannes as the greatest French film of all time, costing more than any French film before it, Les Enfants du Paradis was shot in Paris and Nice during the Nazi occupation and released in 1945. Its sets sometimes had to be moved between the two cities. Its designer and composer, Jews sought by the Nazis, worked from hiding. Carne was forced to hire pro-Nazi collaborators as extras; they did not suspect they were working next to resistance fighters. The Nazis banned all films over about 90 minutes in length, so Carne simply made two films, confident he could show them together after the war was over. The film opened in Paris right after the liberation, and ran for 54 weeks. It is said to play somewhere in Paris every day.

Read the full review at: Roger Ebert

Metrópolis (1927)

Director: Fritz Lang

Writers: Thea von Harbou (screenplay), Thea von Harbou (novel)

Stars: Brigitte Helm, Alfred Abel, Gustav Fröhlich

On Jan. 10, 1927, Fritz Lang’s ”Metropolis,” a wildly ambitious, hugely expensive science fiction allegory of filial revolt, romantic love, alienated labor and dehumanizing technology opened at the Ufa Palast theater in Berlin. Lang’s film, of course, went on to become one of the touchstones of 20th-century cinema, exhaustively studied and endlessly imitated, but apart from its brief theatrical run in Berlin and Nuremberg 75 years ago, the movie as Lang made it has never really been seen.

What happened to ”Metropolis” is, in some ways, a familiar movie-industry story of a studio’s interference with an artist’s work. (Or, if you prefer to side with the studios, of a filmmaker’s profligate indifference to economic necessity and audience response.) A few weeks after the premiere, Ufa, the studio that had produced the film, pulled it from theaters and cut out 7 of the original 12 reels.

Read the rest of this review at: The New York Times

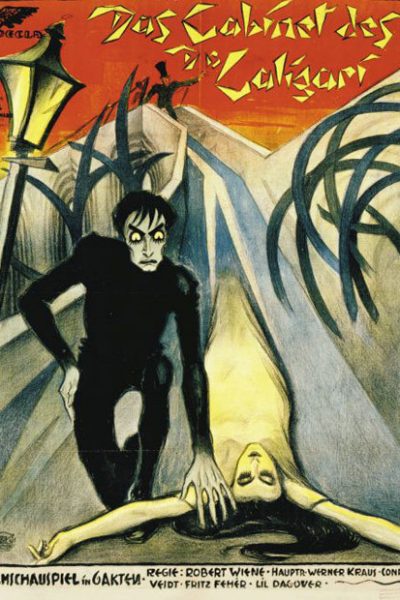

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

Director: Robert Wiene

Writers: Carl Mayer (story and screen play by), Hans Janowitz (story and screen play by)

Stars:Werner Krauss, Conrad Veidt, Friedrich Feher

The first thing everyone notices and best remembers about “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari” (1920) is the film’s bizarre look. The actors inhabit a jagged landscape of sharp angles and tilted walls and windows, staircases climbing crazy diagonals, trees with spiky leaves, grass that looks like knives. These radical distortions immediately set the film apart from all earlier ones, which were based on the camera’s innate tendency to record reality.

The stylized sets, obviously two-dimensional, must have been a lot less expensive than realistic sets and locations, but I doubt that’s why the director, Robert Wiene, wanted them. He is making a film of delusions and deceptive appearances, about madmen and murder, and his characters exist at right angles to reality. None of them can quite be believed, nor can they believe one another.

Read the rest of this review at: Roger Ebert

Las damas del bosque de Bolonia (1945)

Director: Robert Bresson

Writers: Robert Bresson (scenario & adaptation), Denis Diderot (novel)

Stars: Paul Bernard, María Casares, Elina Labourdette

The series of French film revivals that has been running at the Normandie for the last five weeks was topped off yesterday with the showing of two historically important films, each from a prominent director, that have never been shown theatrically in this country. They are “The Crime of Monsieur Lange,” which Jean Renoir made in 1935, and “Les Dames du Bois de Boulougne,” which Robert Bresson made in 1944.

Neither will stand comparison with the technically more expert films of today; and, indeed, it is not difficult to fathom why they probably were not released here previously. For both manifest shortcomings that were no less critical at the time they were made, and time has only served to date them further, so that now they appear complete antiques.

But the student should find them interesting, especially the one of Renoir, which offers some fascinating glints of his developing thoughts and style.

It spins a loose and nondescript story, which ranges uncertainly between romantic comedy and solemn melodrama, about a publishing enterprise in which an author of cheap French Western fiction is the pivotal element.

Read the rest of this review at: The New York Times

Images via Pinterest; Popsugar; AD Magazine FR; @karllagerfeld