What Are The Odds We Are Living In A Computer Simulation

Last week, Elon Musk, the billionaire founder of Tesla Motors, SpaceX, and other cutting-edge companies, took a surprising question at the Code Conference, a technology event in California. What, a man in the audience asked, did Musk make of the idea that we are living not in the real world, but in an elaborate computer simulation? Musk exhibited a surprising familiarity with this concept. “I’ve had so many simulation discussions it’s crazy,” Musk said. Citing the speed with which video games are improving, he suggested that the development of simulations “indistinguishable from reality” was inevitable. The likelihood that we are living in “base reality,” he concluded, was just “one in billions.”

Musk, it seems, has been persuaded by what philosophers call the “simulation argument,” an idea given its definitive form in a 2003 paper by the Oxford philosopher and futurologist Nick Bostrom. (Raffi Khatchadourian profiled Bostrom for this magazine last year.) The simulation argument begins by noticing several present-day trends in technology, such as the development of virtual reality and the mapping of the human brain. (One such mapping effort, the brain Initiative, has been funded by the Obama Administration.) The argument ends by proposing that we are, in fact, digital beings living in a vast computer simulation created by our far-future descendants. Many people have imagined this scenario over the years, of course, usually while high. But recently, a number of philosophers, futurists, science-fiction writers, and technologists—people who share a near-religious faith in technological progress—have come to believe that the simulation argument is not just plausible, but inescapable.

Read the rest of this article at The New Yorker

Body on the Moor

It was the position of the body which somehow seemed strange.

The cyclist who found the man thought he looked like he was having a rest, although it was bitterly cold and the rain was torrential.

The Chew Track, which runs between two reservoirs, is steep. The dead man was positioned on his back perfectly in line with the slope.

Stuart Crowther saw the body while out on one of his regular bike rides.

He was on a small patch of grass, beneath what is known as Rob’s Rocks. “It just seemed odd he was lying so parallel to the path,” Crowther says.

The area is by Saddleworth Moor, part of the Peak District National Park. Many walkers are attracted by the beautiful landscape, the views, the climbs and the colours.

But this man was not wearing anything approaching the right clothing for the walk or the weather – a jacket, shirt, sweater, corduroy trousers and slip-on shoes.

One of the Mountain Rescue volunteers wondered whether he had suffered a heart attack while coming back down the hill.

But when Detective Sergeant John Coleman saw the body, he immediately thought there was something more deliberate.

Coleman is from Greater Manchester Police and leading the investigation to find out who the man was.

More often than not, people are carrying something from which they can be identified – a mobile phone, credit cards, a travel card. But this man had nothing. No wallet, no keys. No clue to who he was. Coleman says it is not unheard of to find no forms of ID on a body. But on such occasions, the police usually find it is just a case of matching the body with someone who is reported missing. Not this time. Six months have now passed since the man on the moor lay down by the path and died, and still no one has even the vaguest notion of who he is. There is only a description — height 6ft 1in, white, slim build, receding grey hair, blue eyes, large nose which might have been broken . . .

Read the rest of this article at BBC

I do not remember my husband’s telephone number, or my best friend’s address. I have forgotten my cousin’s birthday, my seven times table, the date my grandfather died. When I write, I keep at least a dozen internet tabs open to look up names and facts I should easily be able to recall. There are so many things I no longer know, simple things that matter to me in practical and personal ways, yet I usually get by just fine. Apart from the few occasions when my phone has run out of battery at a crucial moment, or the day I accidentally plunged it into hot tea, or the evening my handbag was stolen, it hasn’t seemed to matter that I have downloaded most of my working memory on to electronic devices. It feels a small inconvenience, given that I can access information equivalent to tens of billions of books on a gadget that fits into my back pocket.

Read the rest of this article at NewStatesman

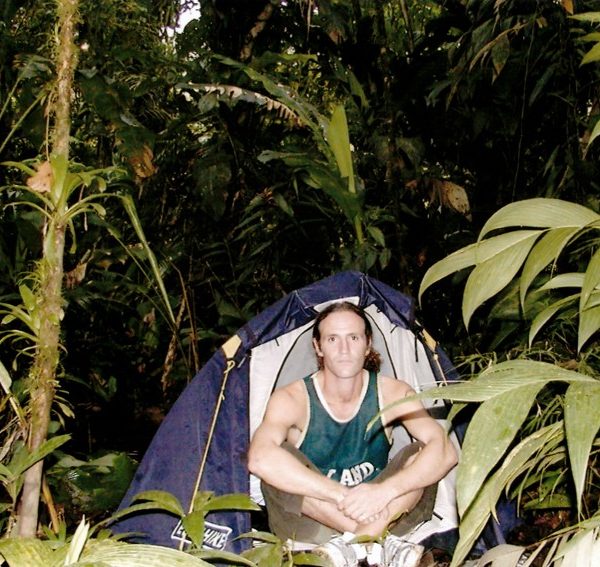

Explorer Lost

These words, typed by Chris Velten, would ultimately lead to his disappearance. Gone without trace — April 2003, somewhere outside the Malian capital of Bamako. But not quite. Over 13 years later, a number of individuals are today coming forward claiming to have seen the would-be 40-year-old alive and well and in Kenya, some 6900km and seven countries away from his vanishing point. But if such sightings are true, how did this bright and charismatic former zoology graduate come to find himself on the other side of the African continent?

More importantly, what happened to him in the hot, wild climes of Mali that led to the bright-eyed 27-year-old remaining far-distant from his family and friends to this day? In an investigation for Love Nature, Jamie Maddison examines the life and ambitions of Chris, and also of his sister Hannah, who continues the search for her brother in Nairobi — her world inextricably linked to that of her sibling, the lost explorer.

Read the rest of this article at Medium

Brain-training games won’t boost your IQ, but a host of strategies can improve your cognitive abilities one piece at a time

Is it just me, or is everybody out there looking for a quick fix? There is something highly compelling about the idea that there is a secret switch we can flip to become suddenly smarter, to reveal cognitive abilities hidden inside each of us. It is a notion that certainly has commercial appeal. Over just seven years, the games-maker Lumosity rocketed from zero to 50 million users, promising rapid improvements in general intelligence by playing brain-training video games for just a few weeks. (Lumosity recently settled with the United States Federal Trade Commission for making unsupported claims that its product was scientifically validated.) ‘Memory health’ nutritional supplements have sales of more than $1.5 billion, and ‘smart drugs’ – pills to enhance cognitive performance – have become prevalent on college campuses. Purveyors of products based on subliminal messages promise to teach us foreign languages and cure our addictions while we sleep. And makers of headgear that attaches electrodes to our scalps promise to rev up our brains to improve gaming performance and other cognitive activities.

These are global trends but, living in the US, it seems to me that there is something particularly American to them. We have a long tradition of positivism, progressivism and self-improvement. Some of this is great. Thomas Edison was convinced that human existence could be dramatically improved with rapid technological innovation, and it is hard to dispute the transformative value of electric light and recorded sound. Henry Wallace looked at the variable and unpredictable yields of Iowa corn farmers and was convinced that scientific breeding and hybridisation could do better than allowing judges to select the most attractive ears at corn shows. His hybrid corn transformed grain farming and launched him on a political career that landed him as Franklin D Roosevelt’s vice president. (However, Wallace’s self-improvement enthusiasm also extended to investigations of psychical communication with the dead, which probably contributed to his getting booted off Roosevelt’s third re-election campaign in favour of Harry S Truman.)

Some of this progressive self-improvement tradition is essential, and some is charming in a kooky way. But part of the drive to engineer a quick fix for what ails us is alarming and dangerous. Americans have endured generations of rapid weight-loss schemes that don’t work and are often dangerous to health – especially diet pills from amphetamines to fen-phen.

Read the rest of this article at aeon