On a warm afternoon last fall, Steven Caron, a technical artist at the video-game company Quixel, stood at the edge of a redwood grove in the Oakland Hills. “Cross your eyes, kind of blur your eyes, and get a sense for what’s here,” he instructed. There was a circle of trees, some logs, and a wooden fence; two tepee-like structures, made of sticks, slumped invitingly. Quixel creates and sells digital assets—the objects, textures, and landscapes that compose the scenery and sensuous elements of video games, movies, and TV shows. It has the immodest mission to “scan the world.” In the past few years, Caron and his co-workers have travelled widely, creating something like a digital archive of natural and built environments as they exist in the early twenty-first century: ice cliffs in Sweden; sandstone boulders from the shrublands of Pakistan; wooden temple doors in Japan; ceiling trim from the Bożków Palace, in Poland. That afternoon, he just wanted to scan a redwood tree. The ideal assets are iconic, but not distinctive: in theory, any one of them can be repeated, like a rubber stamp, such that a single redwood could compose an entire forest. “Think about more generic trees,” he said, looking around. We squinted the grove into lower resolution.

Quixel is a subsidiary of the behemoth Epic Games, which is perhaps best known for its blockbuster multiplayer game Fortnite. But another of Epic’s core products is its “game engine”—the software framework used to make games—called Unreal Engine. Video games have long bent toward realism, and in the past thirty years engines have become more sophisticated: they can now render near-photorealistic graphics and mimic real-world physics. Animals move a lot like animals, clouds cast shadows, and snow falls more or less to expectations. Sound bounces, and moves more slowly than light. Most game developers rely on third-party engines like Unreal and its competitors, including Unity. Increasingly, they are also used to build other types of imaginary worlds, becoming a kind of invisible infrastructure. Recent movies like “Barbie,” “The Batman,” “Top Gun: Maverick,” and “The Fabelmans” all used Unreal Engine to create virtual sets. In 2022, Epic gave the Sesame Workshop a grant to scan the sets for “Sesame Street.” Architects now make models of buildings in Unreal. NASA uses it to visualize the terrain of the moon. Some Amazon warehouse workers are trained in part in gamelike simulations; most virtual-reality applications rely on engines. “It’s really coming of age now,” Tim Sweeney, the founder and C.E.O. of Epic Games, told me. “These little ‘game engines,’ as we called them at the time, are becoming simulation engines for reality.”

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

A physician motions for me to enter the institutional labyrinth of Impfzentrum booths. Once inside, my hands press flat and sticky against my US passport, German residency title and COVID-19 vaccine card. The doctor’s cobalt eyes squint beneath her mask, forming deep frown lines as she peers in suspended bewilderment, muttering at my documents. I ask her to clarify.

‘You’re a Buchleitner and not a native German speaker?!’ Her astonishment and disgust flood me with shame.

What does it mean to return to a land you are supposed to belong to as a descendant but in which you are functionally a foreigner?

Misspelled on my birth certificate with a visible strikethrough, my German family name always proved difficult for Americans, making me an easy target for school-playground bullying and assumptions about my nationality that left me feeling alien. Absent any accompanying grandparents’ memories, recipes, customs or folklore, it remained a phantom identifier with a disembodied lineage.

By divine miracle or sheer coincidence, two months after my first trip to Germany in 2009, where I had a premonition while perched on Heidelberg’s arch bridge that I would return, a distant relative contacted my father with news that felt almost like a premonition: she had painstakingly documented the Buchleitner genealogy from 1520 onward, chronicling the emigration of four sets of ancestors from Saarbrücken to Pennsylvania in the mid-1800s, offering answers to our missing lineage. Craving religious and political freedom, avoiding compulsory military service, and overcoming economic hardship were reasons enough to make a hellish months-long journey to a departure port and then dodge outbreaks of cholera, typhus and smallpox in steerage-class ship accommodations.

When I was leaving Germany, it had seemed as if my ancestors were beckoning me to return. But that wouldn’t happen for another decade, after I became a finalist for the Robert Bosch Foundation Fellowship and fell in love with a German man I’d met in the Temple of the Reclining Buddha in Bangkok. In 2019, I stuffed my keepsakes into three zip-tied suitcases and, though I had no grasp of the German language at all, decided I was migrating to Munich indefinitely.

With a perception of Germany as a methodical, organised utopia to emulate, I assumed my integration would come naturally due to my lineage and new relationship, sooner rather than later granting me an identity to match my name. Within months, however, the assimilation challenges boiled me down to a flicker. Everyday moments of pretending I understood a store clerk’s questions while flanked by impatient customers proved daunting. When strangers barked orders at crosswalks, I awkwardly smiled and nodded. A deep purgatory of straddling an ancestral place that labelled me Ausländerin (foreigner) amassed. ‘Buchleitner’ became something to justify everywhere names matter: from my Frauenärtzin’s (gynecologist’s) office to the Bürgerbüro (citizen’s office) to airport passport control, producing confusion. Everyone wanted to know how an American, sans German husband, sans emigrated German parents, Oma or Opa, could possess such a name.

Read the rest of this article at: Aeon

It’s common to meet the idea of intuition with an eye roll. We tend to value reason over everything else, using expressions like “think before you act,” “think twice,” and “look before you leap.” We don’t trust intuition. In fact, we believe it’s flawed and magical thinking, either vaguely crazy or downright stupid. After all, good decisions should always be reasoned.

What we don’t realize, however, is that intuition is a form of cognition that can actually improve our decision-making.

What is intuition?

You can think of it as an instinct or gut feeling. A knowing or inner wisdom. The internal compass that guides you. Our instincts are meant to keep us away from danger and near safety in a complex world—and even save your life.

It’s an elegant, fine-tuned, and incredibly rapid form of perception. Intuition is a form of cognition meant to guide us and alert us to things we might not otherwise be able to see.

When we speak about our intuition, we often talk of it as a feeling. Something “feels” off, though we can’t necessarily explain why.

We’ve all had gut feelings that we can’t explain. Sometimes, a decision you’re making seems reasonable but doesn’t feel right. Conversely, you may be compelled to do something that seems unreasonable but feels right. The brain is always receiving, perceiving, and processing information that leads you to gain knowledge our logical mind doesn’t always understand or have access to.

Read the rest of this article at: Time

In the fall of 2020, bored and restless in Covid-restricted Spain, Ángel Guerra doodled a dream car. The automotive designer, then 38, wanted to make a tribute to his first four-wheeled love: the time-traveling DeLorean DMC-12 that rolled out of a cloud of steam in Back to the Future. The sketch that took shape on Guerra’s computer had all the iconic elements of the 1980s original—gull-wing doors, stainless-steel cladding, louver blades over the rear window, a rakish black side stripe—plus a few modern touches. Guerra smoothed out the folded-paper angles, widened the body, stretched the wheel arches to accommodate bigger rims and tires. After two weeks, he decided he liked this new DeLorean enough to stick it on Instagram.

The post blew up. Gearheads raved about the design. The music producer Swizz Beatz DM’d Guerra to ask how much it would cost to build. Guerra started to think that maybe his sketch should become a real car. He reached out to a Texas firm called DeLorean Motor Company, which years earlier had acquired the original DeLorean trademarks, but was gently rebuffed. The design seemed destined to live in cyberspace forever. Then, by some algorithmic magic, a different kind of DeLorean showed up on Guerra’s Instagram feed in the spring of 2022—a human DeLorean by the name of Kat. Her posts showcased her love for her puppy, hair dye, and above all her late father, John Z. DeLorean. Although the general public often remembers him as a high-flying CEO with fabulous hair and a surgically augmented chin who went down in a federal sting operation, Guerra chiefly thought of him as a brilliant engineer. He sent Kat a message with some kind words about her dad and a link to the design. Kat saw it and got stoked.

Kat DeLorean is a frequently stoked type of person. At the time, she had recently dyed her long hair in rainbow colors to, in her words, “create the rainbows in my heart on my head.” Yet for much of her life, her relationship to the DeLorean name had been an unhappy one. When people asked why she didn’t own a DMC-12, she would reply: “If there was an iconic representation of your entire life falling apart, would you park it in your driveway?” She would say, only half-jokingly, that the initials stood for “Destroy My Childhood.” A fortysomething cybersecurity professional, Kat lived in a ramshackle farmhouse in New Hampshire with her husband and a few kids. But when Guerra’s note arrived, she was undergoing a pandemic- and work-stress-induced reevaluation of her life’s purpose. She was dreaming up ways to reclaim her father’s legacy. She wanted to launch an engineering education program in his name.

One thing she insisted she didn’t want was to start a car company. It was a car company, after all, that had ruined her father. But then something happened that changed her mind. In April 2022, the Texas company that had given Guerra the cold shoulder announced it would soon reveal a new DeLorean. Kat kept her feelings about this to herself only briefly. First she drew attention to Guerra’s design, posting it on Instagram. (“A timeless classic given the treatment it deserves!”) Two days later, she made her feelings explicit: “@deloreanmotorcompany Is not John DeLorean’s Company,” she wrote. “He despised you.” Details about the new Texas DeLorean emerged a few days after that: Called the Alpha5, it would have four seats instead of two, would reportedly be built mostly from aluminum rather than stainless steel, and would be available in red. Like many DeLorean purists, Kat hated it.

Read the rest of this article at: Wired

The most nauseating, addictive thing about writing is the uncertainty—and I don’t mean the is-anyone-reading? or will-I-make-rent? kind. The uncertainty I’m talking about dogs the very act. This business of writing an essay, for instance: Which of ten thousand possible openings to choose—and how to ignore the sweaty sense that the unseen, unconceptualized ten thousand and first is the real keeper? Which threads to tug at, without knowing where they lead, and which to leave alone? Which ideas to pick up along the way, to fondle and polish and present to an unknown reader? How to know what sentence best comes next, or even what word? A shrewd observer will note that I am complaining about the very essence of writing itself, but that has been the long-held privilege of writers—and they enjoyed it in the secure comfort of their uniqueness. Who else was going to do the writing, if not the writers who grouse about writing?

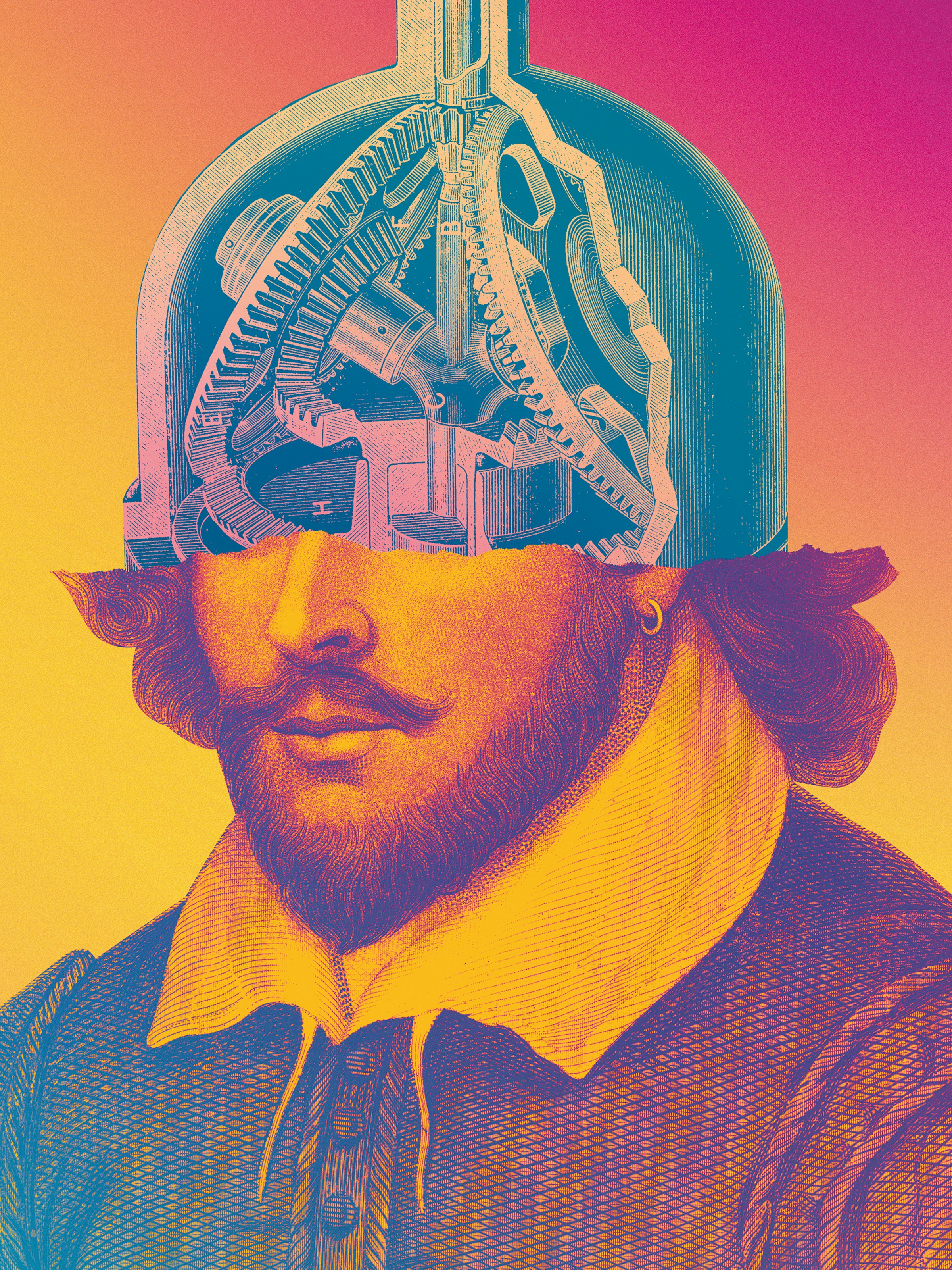

Now along come these language engines, with suspiciously casual or mythopoeic names like ChatGPT or Bard, that suffer not an iota of writerly uncertainty. In what can only be called acts of emesis, they can pour out user manuals, short stories, college essays, sonnets, screenplays, propaganda, or op-eds within seconds of being requested for them. Already, as Naomi S. Baron points out in her book Who Wrote This?, readers aren’t always able to tell if a slab of text came out of a human torturing herself over syntax or a machine’s frictionless innards. (William Blake, it turns out, sounds human, but Gertrude Stein does not.) This unsettles Baron, a linguist who has been writing about the fate of reading for decades now. And it appears to be no lasting consolation that, in some tests, people still correctly recognize an author as artificial. Inexorably, version after version, the AIs will improve. At some point, we must presume, they will so thoroughly master Blakean scansion and a chorus of other voices that their output—the mechanistic term is only appropriate—will feel indistinguishable from ours.

Naturally, this perplexes us. If a computer can write like a person, what does that say about the nature of our own creativity? What, if anything, sets us apart? And if AI does indeed supplant human writing, what will humans—both readers and writers—lose? The stakes feel tremendous, dwarfing any previous wave of automation. Written expression changed us as a civilization; we recognize that so well that we use the invention of writing to demarcate the past into prehistory and history. The erosion of writing promises to be equally momentous.

In an abysmally simplified way, leaving out all mentions of vector spaces and transformer architecture, here’s how a modern large language model, or LLM, works. Since the LLM hasn’t been out on the streets to see cars halting at traffic signals, it cannot latch on to any experiential truth in the sentence, “The BMW stopped at the traffic light.” But it has been fed reams and reams of written material—300 billion words, in the case of ChatGPT 3.5—and trained to notice patterns. It has also been programmed to play a silent mathematical game, trying to predict the next word in a sentence of a source text, and either correcting or reinforcing its guesses as it progresses through the text. If the LLM plays the game long enough, over 300 billion or so words, it simulates something like understanding for itself: enough to determine that a BMW is a kind of car, that “traffic light” is a synonym for “traffic signal,” and that the sentence is more correct, as far the real world goes, than “The BMW danced at the traffic light.” Using the same prediction algorithms, the LLM spits out plausible sentences of its own—the words or phrases or ideas chosen based on how frequently they occur near one another in its corpus. Everything is pattern-matching. Everything—even poetry—is mathematics.

Read the rest of this article at: The New Republic