The Class Pay Gap: Why It Pays To Be Privileged

Mark has one of the most coveted jobs in television. As a senior commissioner at one of Britain’s biggest broadcasters, he controls a budget extending to the millions. And every day, a steady stream of independent television producers arrive at his desk desperate to land a pitch. At just 39, Mark is young to wield such power. After making his name as a programmemaker, he initially became a commissioner at a rival broadcaster before being headhunted five years ago. A string of hits later, he is now one of the industry’s biggest players.

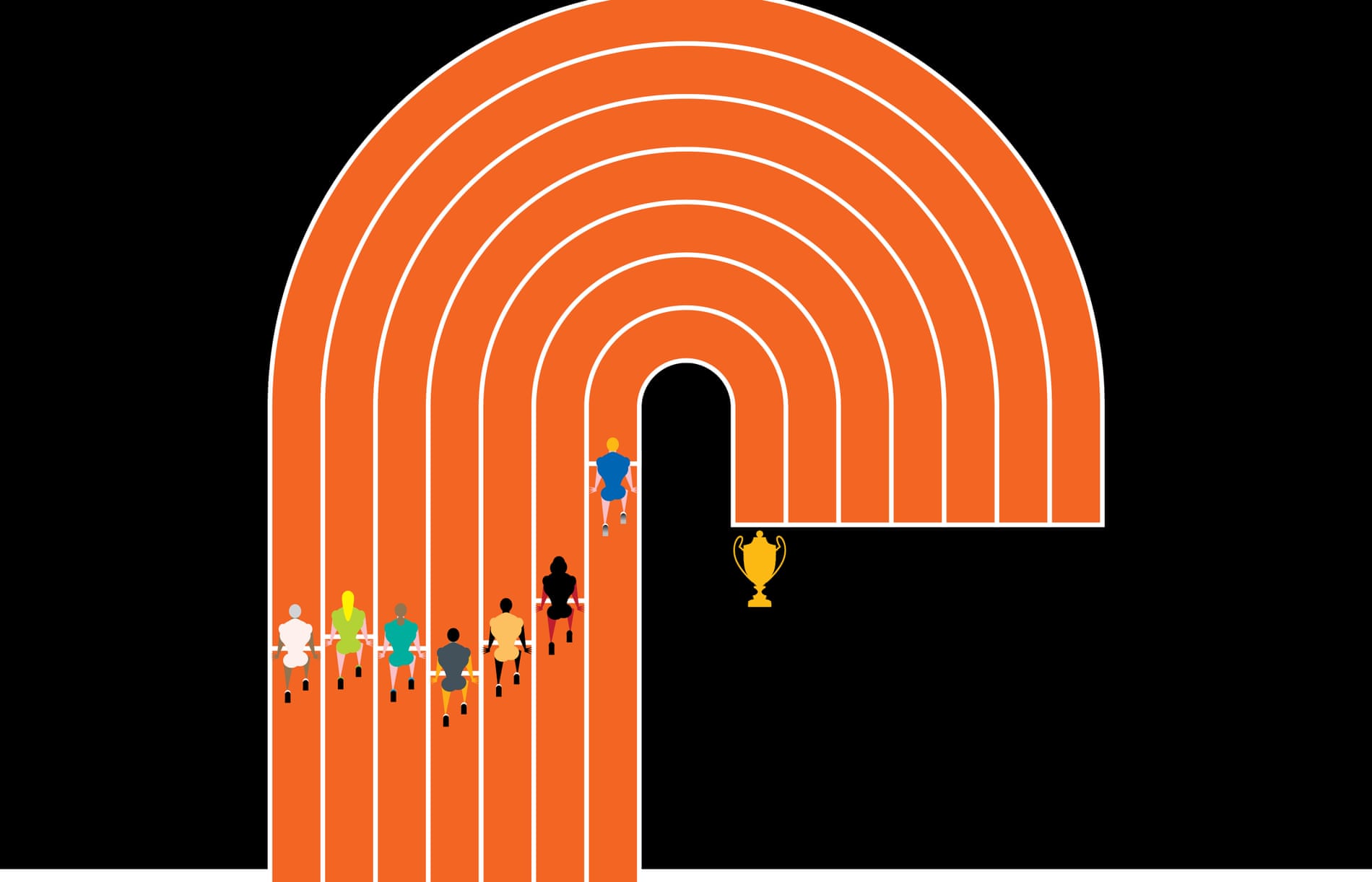

Yet when we met Mark, and invited him to narrate his career in his own words, a very different account emerged. It is not that he disavowed his success; he is clearly proud of what he has achieved. But what is striking is Mark’s acknowledgment that his upward trajectory, particularly its rapid speed and relative smoothness, has been contingent on “starting the race” with a series of profound advantages. He is certainly from a privileged background. His parents were both successful professionals and he was educated at one of London’s top private schools before going on to Oxford.

“It is not like I think I am rubbish,” he said towards the end of our interview. “I’ve seen lots of peers with greater networks and privilege screw up because they just weren’t good enough. But at the same time, it is mad to pretend there’s not been an incredibly strong following wind throughout my career.”

Read the rest of this article at: The Guardian

The Desperado

Edward Averill finished off the last slices of Genoa salami and sopressata from the deli packages in his mini-fridge, rolling them into tubes and eating them with his fingers. Between bites he drank a Modelo Especial. It was his favorite beer, and that night, April 5, 2018, he savored every sip. He didn’t expect to have another one anytime soon.

The 58-year-old computer engineer climbed into bed around 10 p.m. and lay staring at the ceiling for hours before drifting off to sleep. He jerked awake without an alarm at 8:30 the next morning. After turning on his laptop and scrubbing it clean of files and software, he wiped his external hard drive and reformatted it—twice. Satisfied, he powered down the computer and began tidying his room.

There wasn’t much there. He rented it from a woman named Anne Toney, who owned the house it was in. The rest of Toney’s home was cluttered—chairs, gnome figurines, even an old, empty candy machine. Averill liked to joke that people had vanished there amid all the bric-a-brac. But he took pride in his space, which was big enough for a double bed, the magnet-covered fridge, and a media cabinet he used as a pantry. He set drinks on coasters so they wouldn’t leave rings on his computer desk, which is where he ate most of his meals.

Over the previous week, he’d thrown away many of his belongings, including five USB sticks, a Swiffer, and an extra computer monitor. On the morning of April 6, he tossed the magnets and coasters, too. All that was left, aside from the furniture, were some clothes in the closet, a couple of cold beers, and a blue expandable plastic folder where he stored sensitive paperwork like his birth certificate and Social Security card. Old tax forms were in one sleeve; his diploma from Oakton High School in Vienna, Virginia, was in another.

Read the rest of this article at: the Atavist Magazine

A New Americanism

In 1986, the Pulitzer Prize–winning, bowtie-wearing Stanford historian Carl Degler delivered something other than the usual pipe-smoking, scotch-on-the-rocks, after-dinner disquisition that had plagued the evening program of the annual meeting of the American Historical Association for nearly all of its centurylong history. Instead, Degler, a gentle and quietly heroic man, accused his colleagues of nothing short of dereliction of duty: appalled by nationalism, they had abandoned the study of the nation.

“We can write history that implicitly denies or ignores the nation-state, but it would be a history that flew in the face of what people who live in a nation-state require and demand,” Degler said that night in Chicago. He issued a warning: “If we historians fail to provide a nationally defined history, others less critical and less informed will take over the job for us.”

Read the rest of this article at: Foreign Affairs

In Defense Of Schadenfreude

Tiffany Watt Smith is a historian of emotions. How’s that for a profession? In The Book of Human Emotions, which came out in 2016, Smith profiles 154 emotions in sharp, concise bursts. Torschlusspanik, she writes, “describes the agitated, fretful feeling we get when we notice time is running out.” (The German term translates as “gate-closing panic.”) The Japanese word amae refers to the “sensation of temporary surrender in perfect safety.” And there is a two page–long entry on schadenfreude—“from the German Schaden (harm) and Freude (pleasure)”—that often-shameful feeling of pleasure at another’s pain.

In her new book, Schadenfreude: The Joy of Another’s Misfortune, Smith—who is a Wellcome Trust research fellow at the Centre for the History of the Emotions at Queen Mary University of London—takes a close look at the various flavors of this feeling. There is the schadenfreude we feel witnessing someone else’s accident, the burst of joy when our rival falters, the satisfaction when justice is served, the pleasure of watching the morally superior get their comeuppance. There is sibling rivalry (and sibling-esqure rivalry in the workplace). There is the guilty pleasure when a friend we envy suffers a disappointment.

Smith makes reading about schadenfreude fun. She also convincingly levies the broad argument that, although there are circumstances in which it can be dangerous, schadenfreude is a vital part of the way we relate to one another and doesn’t deserve to be held in such poor esteem. I spoke with Smith by phone about the nuances of schadenfreude and her experience writing about this much-judged emotion.

Read the rest of this article at: Longreads

How SoftBank Ate The World

On the morning of July 20, 2017, at the luxurious Prince Park Tower hotel in Tokyo, Masayoshi Son emerged on stage in front of a packed conference hall, his diminutive silhouette backlit by bright white lights. Son, the CEO of Japanese internet, energy and financial conglomerate SoftBank Group, was dressed simply, as is his habit, in a grey suit and a striped shirt. He smiled and introduced himself in Japanese.

Son is known for his fanciful analogies and long speeches. In 2010, his talk about his “300-year plan for the future” opened with a reflection on the nature of sorrow, with Son asking rhetorically, “What is the saddest thing in life? What gives you utmost happiness?” In 2016, he equated the Internet of Things (IoT) to the Cambrian era’s explosion of life, comparing the evolutionary advantage conferred to the first species with eyes to the combination of sensors and AI enabled by the IoT.

Addressing hundreds of technologists and entrepreneurs, he compared SoftBank to the gentry of the Industrial Revolution, a privileged class that invested in technology and science for the common good. Two months earlier, SoftBank had launched a $100 billion investment arm, the Vision Fund – the biggest tech fund in history. In Son’s metaphor, the Vision Fund was the gentry of the information revolution. “I really don’t want to go to sleep,” he said. “I don’t want to waste time. These are very exciting times.”

Many of the CEOs in the audience that day were recipients of the fund’s investment. Without exception, they had all met Son privately, either in his office in Shiodome, Tokyo, or in his $117.5 million mansion in Woodside, California. Most describe the legendary investor – known as Masa – as soft-spoken, a man with a modest bearing and a prescient vision of the future: a reputation substantiated by his achievements.

In the 1970s, Son emigrated to America to study. At the time, he had only a rudimentary knowledge of English, and made his first million by importing Japanese arcade games such as Space Invaders. It was Son who, in 1996, offered budding entrepreneur Jerry Yang, then CEO of a struggling startup called Yahoo!, $100m in investment. His insight paid off. By 2000, Yahoo! had become the dominant web search engine in the pre-crash era of the internet.

Read the rest of this article at: Wired