If you’ve been enjoying these curated article summaries that dive into cultural, creative, and technological currents, you may find the discussions and analyses on our Substack page worthwhile as well. There, I explore themes and ideas that often intersect with the subjects covered in the articles I come across during my curation process.

While this curation simply aims to surface compelling pieces, our Substack writings delve deeper into topics that have piqued our curiosity over time. From examining the manifestation of language shaping our reality to unpacking philosophical undercurrents in society, our Substack serves as an outlet to unpack our perspectives on the notable trends and undercurrents reflected in these curated readings.

So if any of the articles here have stoked your intellectual interests, I invite you to carry that engagement over to our Substack, where we discuss related matters in more depth. Consider it an extension of the curation – a space to further engage with the fascinating ideas these pieces have surfaced.

While scrolling TikTok in 2022, Kaylen came across something unexpected: a video about relationships and anxiety, made by her therapist. She wasn’t sure how it found her, since they didn’t have each other’s numbers. But what was most remarkable about this experience was that it had happened before. She had come across her previous therapist online on YouTube in 2022 and had been uncomfortable then, too.

“That was actually part of the reason why I was like ‘I think I’m going to stop therapy for a while,’” the Los Angeles-based 29-year-old says.

The stars of TherapyTok, as it’s called, pull in numbers not dissimilar to the artists and influencers who found mainstream fame on the app. A video about suicide warning signs has more than 9 million views. So does another about whether or not you’re in “freeze mode.” Those posts are among the tens of thousands of contributions psychologists have made to the platform. However, despite their popularity, and the rise of things like “therapy speak,” users have conflicted feelings about seeing their own mental health professional in front of the camera.

“It’s like when you’re a kid and you see your teacher at the supermarket,” says Ashley, who is 30 years old and from Brooklyn. Ashley started getting served her own therapist’s content after sending her a TikTok that was relevant to their sessions. “You’re like, ‘You’re not allowed to be here,’” she jokes.

It would be a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) violation for a psychologist to discuss their private sessions with others. But with life now lived significantly online, a rising number of therapists are using social media tools to grow and promote their practice — and the normal boundaries are blurred.

“There isn’t a lot of information of how to navigate it,” says Ernesto Lira de la Rosa, Ph.D., clinical assistant professor at New York University’s Department of Applied Psychology. “[But] we do spend a lot of time in our introduction to the profession and ethics class talking about this.”

Broadly, students are advised to protect both themselves and the field’s reputation by disclosing their social media presence to their clients and to be mindful of the potential impact of the information they’re sharing online, knowing it might be received inaccurately.

“I see clients come in saying ‘I have ADHD or I have anxiety,’” he says. “And as I start asking more — ‘When were you diagnosed?’ — [they say] ‘Oh, well I saw on TikTok someone said these are the symptoms.’”

Some therapists are motivated to create content that counteracts what they feel is a widespread misunderstanding of mental health information. Bay Area psychotherapist Meg Josephson began posting online in hopes of doing just that, but her TikTok account, which now has 250,000 followers, ended up becoming a vital way to promote her practice. Now, she says, most of her clients say they came to her from her social media, and it recently landed her a book deal.

Read the rest of this article at: Bustle

In the weeks after Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte seized power and declared himself Napoleon III, Emperor of the French, Karl Marx sat down to write a history of the present. The purpose of this work was straightforward. Marx wanted to understand how the class struggle in France had ‘made it possible for a grotesque and mediocre personality to play a hero’s part.’ Much of The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (1852/69), as the work would be known, accordingly consisted of fine-grained political and economic analysis. But Marx opened in a more philosophical vein. After quipping that history repeats itself first as tragedy and then as farce, he reflected upon the role that historical parallelism played in shaping revolutionary action:

The tradition of all the dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brain of the living. And just when they seem engaged in revolutionising themselves and things, in creating something that has never yet existed, precisely in such periods of revolutionary crisis they anxiously conjure up the spirits of the past to their service and borrow from them names, battle-cries and costumes in order to present the new scene of world history in this time-honoured disguise and this borrowed language.

This tendency had pervaded European history, Marx thought, and occasionally served the ends of progress. The cloak of Roman republicanism, for instance, had helped French society lurch blindly forward during the revolution of 1789. In the present case, however, the appropriated symbolism of that earlier revolution served no higher purpose than to veil a grifter’s power grab in a more compelling guise.

Marx points toward one of the more paradoxical tendencies of modern political life: the more times feel unprecedented, the more we reach for past parallels. We do so, however, not only to legitimate new regimes. Just as often, historical analogies are invoked to explain, predict and condemn. The past decade alone offers a trove of examples. Among them, the use of ‘fascism’ to characterise Right-wing populist movements has generated the most heat, giving rise to a multifaceted debate about the legitimacy of historical analogy as a mode of political analysis. But there are others that have occasioned less self-reflection. In reckoning with the possibility of open conflict between the United States and China, for instance, foreign policy experts have routinely likened the escalating tension to the Cold War, the First World War, and even the Peloponnesian War. Similarly, in the early days of COVID-19, many dealt with the uncertainty of the pandemic by turning to the Spanish Flu, the Black Death, and the Great Plague of Athens for guidance. Something of the sort is also happening in real time with generative AI. How we interpret the risk that it poses hinges in large part on which analogy we favour: will it be most akin to the Industrial Revolution, the nuclear bomb, or – perhaps most horrifying of all – the consulting firm McKinsey?

Read the rest of this article at: Aeon

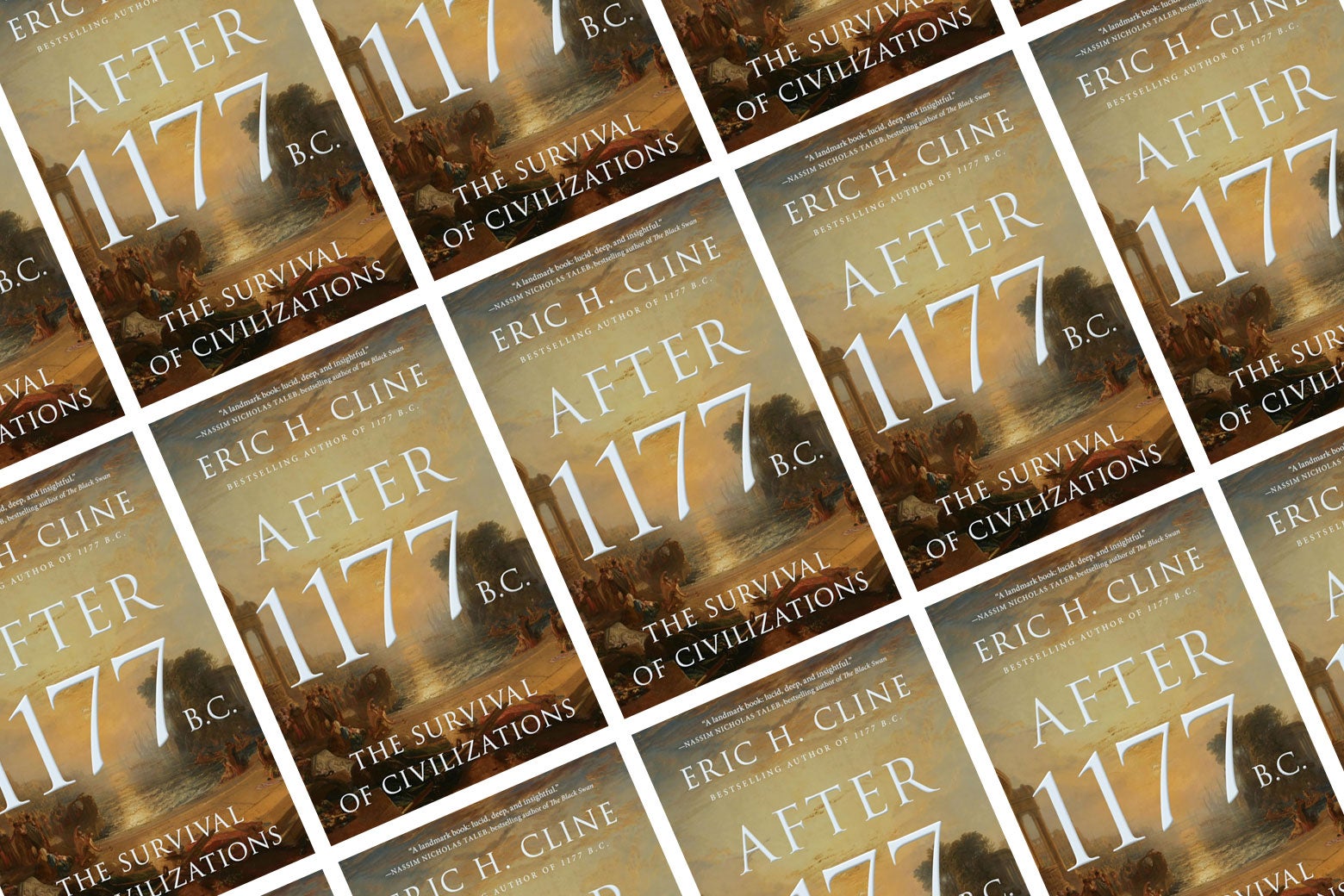

Ten years ago, archaeologist Eric Cline’s book 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed became a surprise critical and commercial hit and a nominee for the Pulitzer Prize.* It’s since been translated into 16 languages (and, recently, into a graphic-novel-like format) and keeps finding new readers. I read it in the summer of 2017 while honeymooning in Crete, a place whose Minoan civilization figures prominently in Cline’s narrative. My wife and I were struggling to think and plan hopefully for the future at a time when our own nation back home seemed to be tottering. There was something strangely grounding in reading about the more or less sudden evaporation of a handful of Late Bronze Age societies, likely caused by some combination of climate change, famine, political upheaval, and mass migration. The book was frightening in its contemporary implications—not least in showing how the deep interconnectedness of that lost world went, almost overnight, from being a strength to a vulnerability. Once things started going haywire, nations toppled like dominoes. But I also found Cline’s book somehow reassuring. Empires rise and fall, always have—so what? Life goes on. We had our first child the following year.

Read the rest of this article at: Slate

On a subway train not long ago, I had the familiar, unsettling experience of standing behind a fellow-passenger and watching everything that she was doing on her phone. It was a crowded car, rush hour, with the dim but unwarm lighting of the oldest New York City trains. The stranger’s phone was bright, and as I looked on she scrolled through a waterfall of videos that other people had filmed in their homes. She watched one for four or five seconds, then dispatched it by twitching her thumb. She flicked to a text message, did nothing with it, and flipped back. The figures on her screen, dressed carefully and mugging at the camera like mimes, seemed desperate for something that she could not provide: her sustained attention. I felt mortified, not least because I saw on both sides of the screen symptoms I recognized too clearly in myself.

For years, we have heard a litany of reasons why our capacity to pay attention is disturbingly on the wane. Technology—the buzzing, blinking pageant on our screens and in our pockets—hounds us. Modern life, forever quicker and more scattered, drives concentration away. For just as long, concerns of this variety could be put aside. Television was described as a force against attention even in the nineteen-forties. A lot of focussed, worthwhile work has taken place since then.

But alarms of late have grown more urgent. Last year, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development reported a huge ten-year decline in reading, math, and science performance among fifteen-year-olds globally, a third of whom cited digital distraction as an issue. Clinical presentations of attention problems have climbed (a recent study of data from the medical-software company Epic found an over-all tripling of A.D.H.D. diagnoses between 2010 and 2022, with the steepest uptick among elementary-school-age children), and college students increasingly struggle to get through books, according to their teachers, many of whom confess to feeling the same way. Film pacing has accelerated, with the average length of a shot decreasing; in music, the mean length of top-performing pop songs declined by more than a minute between 1990 and 2020. A study conducted in 2004 by the psychologist Gloria Mark found that participants kept their attention on a single screen for an average of two and a half minutes before turning it elsewhere. These days, she writes, people can pay attention to one screen for an average of only forty-seven seconds.

“Attention as a category isn’t that salient for younger folks,” Jac Mullen, a writer and a high-school teacher in New Haven, told me recently. “It takes a lot to show that how you pay attention affects the outcome—that if you focus your attention on one thing, rather than dispersing it across many things, the one thing you think is hard will become easier—but that’s a level of instruction I often find myself giving.” It’s not the students’ fault, he thinks; multitasking and its euphemism, “time management,” have become goals across the pedagogic field. The SAT was redesigned this spring to be forty-five minutes shorter, with many reading-comprehension passages trimmed to two or three sentences. Some Ivy League professors report being counselled to switch up what they’re doing every ten minutes or so to avoid falling behind their students’ churn. What appears at first to be a crisis of attention may be a narrowing of the way we interpret its value: an emergency about where—and with what goal—we look.

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

The cartoon of Jerry Seinfeld is that he is the comedian who goes on “about nothing.” The nihilist of the Upper West Side. And yet Seinfeld is, like Chris Rock and few others in comedy, as serious and self-conscious about his craft as the best musicians. We were once having a conversation in front of an audience at the Society for Ethical Culture, on West Sixty-fourth Street, and, after a few minutes, he stopped to take note of the echo in the hall. The way the echo affected how the audience took in his jokes. And the subsequent effect on the quality of the laughs.

Seinfeld made a fortune with “Seinfeld.” He could easily have lived out the rest of his life going to Mets games and eating cereal. Instead, he writes jokes for hours each day, as disciplined as a concert pianist. Larry David, of course, was his partner in creating “Seinfeld,” and Seinfeld appeared from time to time in David’s long-running HBO series, “Curb Your Enthusiasm.”

Seinfeld’s series “Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee” indulged his passion for cars, sure, but it was really about his comedian friends, their common craft, and their joy in talking––freely and without inhibition. In 2020, he published “Is This Anything?,” which contains some of his best standup work but also delves into his craft and his devotion to it.

And now, for the first time, he has directed a movie. It is about a Russian Orthodox monk in the sixteenth century who starves himself to death rather than give in to the depredations of tsarist society. No, it isn’t. It’s about the race in the early sixties between Kellogg and Post to invent the Pop-Tart. Yes, really. It is called “Unfrosted” and will air on Netflix on May 3rd. It is extremely silly, in a good way.

Seinfeld came to our studio at One World Trade Center for The New Yorker Radio Hour. He was very well dressed and in good spirits. He immediately started ripping me to shreds. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity and sometimes to preserve my ego and dignity—though no editing could manage that entirely.

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker