On December 15, 1811, the London Statesman issued a warning about the state of the stocking industry in Nottingham. Twenty thousand textile workers had lost their jobs because of the incursion of automated machinery. Knitting machines known as lace frames allowed one employee to do the work of many without the skill set usually required. In protest, the beleaguered workers had begun breaking into factories to smash the machines. “Nine Hundred Lace Frames have been broken,” the newspaper reported. In response, the government had garrisoned six regiments of soldiers in the town, in a domestic invasion that became a kind of slow-burning civil war of factory owners, supported by the state, against workers. The article was apocalyptic: “God only knows what will be the end of it; nothing but ruin.”

The workers destroying the lace frames were the group who called themselves Luddites, after Ned Ludd, a (likely fictional) knitting-frame apprentice near Leicester who was said to have rebelled against his boss by destroying a frame with a hammer. Today, the word “Luddite” is used as an insult to anyone resistant to technological innovation; it suggests ignoramuses, sticks in the mud, obstacles to progress. But a new book by the journalist and author Brian Merchant, titled “Blood in the Machine,” argues that Luddism stood not against technology per se but for the rights of workers above the inequitable profitability of machines. The book is a historical reconsideration of the movement and a gripping narrative of political resistance told in short vignettes.

The hero of the story is George Mellor, a young laborer from Huddersfield who worked as a so-called cropper, smoothing the raised surface of rough cloth with shears. He observed the increasing automation of the industry, concluded that it was unjust, and decided to join the insurgent Luddite movement. A physically towering figure, he organized his fellow-workers and led attacks on factories. One factory owner who was targeted was William Horsfall, a local cloth entrepreneur. Horsfall threatened to ride his horse through “Luddite blood” in order to keep his profitable factories going, hiring mercenaries and installing cannons to defend his machines. In the background of the story, figures such as the ineffectual Prince George, a sybaritic regent for his infirm father, George III, and Lord Byron, the poet, who voiced his sympathy for the Luddites in Parliament, debate which side to support: owners or workers. Byron exhorted the workers in his poem “Song for the Luddites” to “die fighting, or live free.”

Merchant ably demonstrates the dire stakes of the Luddites’ plight. The trades that had sustained livelihoods for generations were disappearing, and their families were starving. A Lancashire weaver’s weekly pay dropped from twenty-five shillings in 1800 to fourteen in 1811. The market was being flooded with cheaper, inferior goods such as “cut-ups,” stockings made from two pieces of cloth joined together, rather than knit as one continuous whole. The government repeatedly failed to intervene on behalf of the workers. What option remained was attacking the boss’s capital by disabling the factories. The secretive captains of the Luddite forces took on the pseudonym General Ludd or King Ludd, which they used to write public letters and to sign threats of attacks. The spectre of violence led some factory owners to abandon their plans for automation. They reverted to manual labor or closed up shop completely. For a time, it seemed that the Luddites were making headway in empowering themselves over the machines.

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

On a brisk day in February, 2004, Dante Lauretta, an assistant professor of planetary science at the University of Arizona, got a call from Michael Drake, the head of the school’s Lunar and Planetary Laboratory. “I have Lockheed Martin in my office,” Drake said. “They want to fly a spacecraft to an asteroid and bring back a sample. Are you in?”

The two men met that evening with Steve Price, then a director of business development for Lockheed Martin Space, on the patio of a hotel bar in Tucson. Over drinks, they scribbled ideas on cocktail napkins. Price explained that the company’s engineers had developed technology that would allow a spacecraft about the size of a mail truck to rendezvous with a near-Earth asteroid, then enter a hummingbird-like mode and “kiss” its surface. The craft’s “beak” would be an unfolding eleven-foot-long mechanism with a cannister on its end, which would kick up material with a little blast of nitrogen. The spacecraft would stow this bounty in a protective capsule, fly back home, and then parachute it to Earth.

Asteroids interest researchers for many reasons. Because most predate the existence of the Earth, they harbor clues about the solar system’s long history. They often contain valuable industrial elements, such as cobalt and platinum, which are getting harder to find terrestrially. In the future, they might provide astronauts with fuel, oxygen, water, and construction material. And they can also pose a threat: in 2004, astronomers discovered that an asteroid named Apophis had an almost three-per-cent chance of striking Earth in 2029, conceivably killing millions. (It’s now projected to miss us by around twenty thousand miles—the equivalent of a round-trip flight from New York to Sydney.)

Although there is no life on asteroids that we know of, biochemists are interested in them, too. At some point in the Earth’s history, chemistry became biology: simpler molecules reacted with prebiotic molecules, and these in turn combined to create DNA, RNA, proteins, and other components of life. The precise conditions that caused this are impossible to determine, because eons of upheaval, including plate tectonics, have left the geologic record of Earth’s distant past incomplete. But asteroids—the building blocks of planets, frozen in time billions of years ago—offer chemical snapshots of what our planet was like before life existed. By crashing to Earth as meteors, they have also added to the planet’s chemical complexity. Many scientists now think that important chemical components of life weren’t cooked up on Earth but delivered, by asteroids, from the larger cauldron of the early solar system. Analyzing a sample retrieved from an asteroid could shed light on where biochemistry came from.

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

The Morrissey had the right melodrama in his limbs, and his voice was strong and pained. I was at Gramercy Theatre in Manhattan to see a Smiths tribute band. I tried to get Morrissey’s acid yodel in my throat, to sing along. I am human and I need to be loved / just like everybody else does. But it didn’t feel right to copy a copy.

Most tribute bands don’t practice outright impersonation, so the way this fake-Smiths singer captured everything about Morrissey was messing with my mind. I’d hoped to be able to savor the music’s maudlin glory without the headache of the flesh-and-blood Morrissey, who seems to have aligned himself with white supremacists. The contempt in Morrissey’s lyrics and politics was presumably not native to Seanissey, as the tribute singer called himself. Seanissey’s performance probably didn’t, as they say, “come from a bad place”—or a misanthropic place, or a far-right place, or even a vegan one.

Read the rest of this article at: Wired

The half-bearded behavioral economist Dan Ariely tends to preface discussions of his work—which has inquired into the mechanisms of pain, manipulation, and lies—with a reminder that he comes by both his eccentric facial hair and his academic interests honestly. He tells a version of the story in the introduction to his breezy first book, “Predictably Irrational,” a patchwork of marketing advice and cerebral self-help. One afternoon in Israel, Ariely—an “18-year-old military trainee,” according to the Times—was nearly incinerated. “An explosion of a large magnesium flare, the kind used to illuminate battlefields at night, left 70 percent of my body covered with third-degree burns,” he writes. He spent three years in the hospital, a period that estranged him from the routine practices of everyday life. The nurses, for example, stripped his bandages all at once, as per the cliché. Ariely suspected that he might prefer a gradual removal, even if the result was a greater sum of agony. In an early psychological experiment he later conducted, he submitted this instinct to empirical review. He subsequently found that certain manipulations of an unpleasant experience might make it seem milder in hindsight. In onstage patter, he referred to a famous study in which researchers gave colonoscopy patients either a painful half-hour procedure or a painful half-hour procedure that concluded with a few additional minutes of lesser misery. The patients preferred the latter, and this provided a reliable punch line for Ariely, who liked to say that the secret was to “leave the probe in.” This was not, strictly speaking, optimal—why should we prefer the scenario with bonus pain? But all around Ariely people seemed trapped by a narrow understanding of human behavior. “If the nurses, with all their experience, misunderstood what constituted reality for the patients they cared so much about, perhaps other people similarly misunderstand the consequences of their behaviors,” he writes. “Predictably Irrational,” which was published in 2008, was an instant airport-book classic, and augured an extraordinarily successful career for Ariely as an enigmatic swami of the but-actually circuit.

Ariely was born in New York City in 1967 and grew up north of Tel Aviv; his father ran an import-export business. He studied psychology at Tel Aviv University, then returned to the United States for doctoral degrees in cognitive psychology at the University of North Carolina and in business administration at Duke. He liked to say that Daniel Kahneman, the Nobel Prize-winning Israeli American psychologist, had pointed him in this direction. In the previous twenty years, Kahneman and his partner, Amos Tversky, had pioneered the field of “judgment and decision-making,” which revealed the rational-actor model of neoclassical economics to be a convenient fiction. (The colonoscopy study that Ariely loved, for example, was Kahneman’s.) Ariely, a wily character with a vivid origin story, presented himself as the natural heir to this new science of human folly. In 1998, with his pick of choice appointments, he accepted a position at M.I.T. Despite having little training in economics, he seemed poised to help renovate the profession. “In Dan’s early days, he was the most celebrated young intellectual academic,” a senior figure in the discipline told me. “I wouldn’t say he was known for being super careful, but he had a reputation as a serious scientist, and was considered the future of the field.”

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

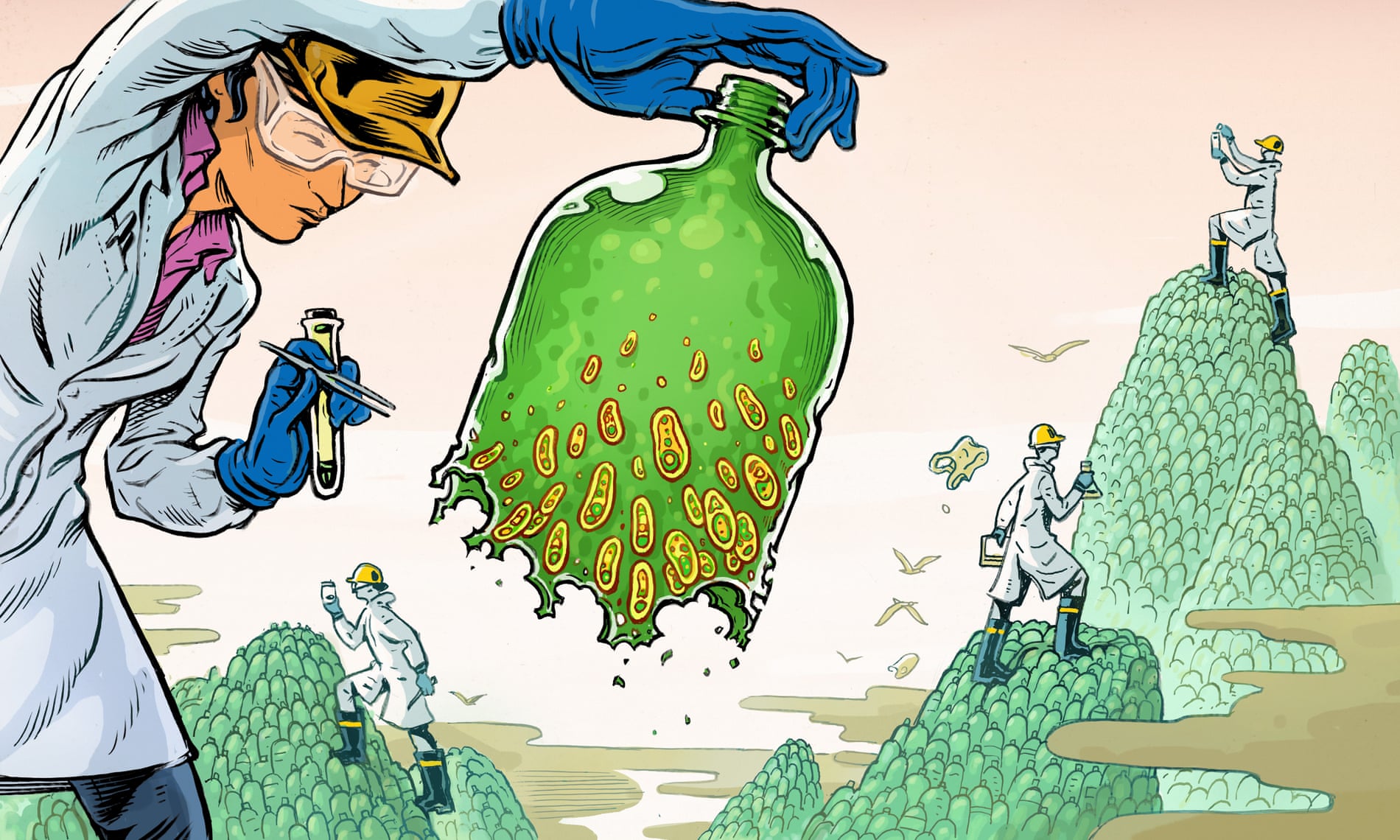

In 2001, a group of Japanese scientists made a startling discovery at a rubbish dump. In trenches packed with dirt and waste, they found a slimy film of bacteria that had been happily chewing through plastic bottles, toys and other bric-a-brac. As they broke down the trash, the bacteria harvested the carbon in the plastic for energy, which they used to grow, move and divide into even more plastic-hungry bacteria. Even if not in quite the hand-to-mouth-to-stomach way we normally understand it, the bacteria were eating the plastic.

The scientists were led by Kohei Oda, a professor at the Kyoto Institute of Technology. His team was looking for substances that could soften synthetic fabrics, such as polyester, which is made from the same kind of plastic used in most beverage bottles. Oda is a microbiologist, and he believes that whatever scientific problem one faces, microbes have probably already worked out a solution. “I say to people, watch this part of nature very carefully. It often has very good ideas,” Oda told me recently.

What Oda and his colleagues found in that rubbish dump had never been seen before. They had hoped to discover some micro-organism that had evolved a simple way to attack the surface of plastic. But these bacteria were doing much more than that – they appeared to be breaking down plastic fully and processing it into basic nutrients. From our vantage point, hyperaware of the scale of plastic pollution, the potential of this discovery seems obvious. But back in 2001 – still three years before the term “microplastic” even came into use – it was “not considered a topic of great interest”, Oda said. The preliminary papers on the bacteria his team put together were never published.I

In the years since the group’s discovery, plastic pollution has become impossible to ignore. Within that roughly 20-year span, we have generated 2.5bn tonnes of plastic waste and each year we produce about 380 million tonnes more, with that amount projected to triple again by 2060. A patch of plastic rubbish seven times the size of Great Britain sits in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, and plastic waste chokes beaches and overspills landfills across the world. At the miniature scale, microplastic and nanoplastic particles have been found in fruits and vegetables, having passed into them through the plants’ roots. And they have been found lodged in nearly every human organ – they can even pass from mother to child through breast milk.

Current methods of breaking down or recycling plastics are woefully inadequate. The vast majority of plastic recycling involvesa crushing and grinding stage, which frays and snaps the fibres that make up plastic, leaving them in a lower-quality state. While a glass or aluminium container can be melted down and reformed an unlimited number of times, the smooth plastic of a water bottle, say, degrades every time it is recycled. A recycled plastic bottle becomes a mottled bag, which becomes fibrous jacket insulation, which then becomes road filler, never to be recycled again. And that is the best case scenario. In reality, hardly any plastic – just 9% – ever enters a recycling plant. The sole permanent way we’ve found to dispose of plastic is incineration, which is the fate of nearly 70 million tonnes of plastic every year – but incineration drives the climate crisis by releasing the carbon in the plastic into the air, as well as any noxious chemicals it might be mixed with.

Read the rest of this article at: The Guardian