In July, 1918, Virginia Woolf spent a weekend at Garsington—a country home, outside Oxford, owned by Lady Ottoline Morrell, a celebrated hostess of the era, and her husband, Philip Morrell, a Member of Parliament. The house, a ramshackle Jacobean mansion that the Morrells had acquired five years earlier, had been vividly redecorated by Ottoline into what one guest called a “fluttering parrot-house of greens, reds and yellows.” One sitting room was painted with a translucent seafoam wash; another was covered in deep Venetian red, and early visitors were invited to apply thin lines of gold paint to the edges of wooden panels. The entrance hall was laid with Persian carpets and, as Morrell’s biographer Miranda Seymour has written, the pearly gray paint on the walls was streaked with pink, “to create the effect of a winter sunset.” Woolf, in her diary, noted that the Italianate garden fashioned by Morrell—with paved terraces, brilliantly colored flower beds, and a pond surrounded by yew-tree hedges clipped with niches for statuary—was “almost melodramatically perfect.”

Woolf characterized Morrell herself with a note of satire, observing that her conversational “drift is always almost bewilderingly meandering.” While on an afternoon walk, Morrell had leaned on a parasol and offered a discourse on love—“Isn’t it sad that no one really falls in love nowadays?”—before declaring her dedication to the natural world and to literature. “We asked the poor old ninny why, with this passion for literature, she didn’t write,” Woolf wrote. Morrell replied, “Ah, but I’ve no time—never any time. Besides, I have such wretched health—But the pleasure of creation, Virginia, must transcend all others.”

Morrell, who was born in 1873, just nine years before Woolf—hardly an old-ninny interval—may not have written novels, but she certainly took pleasure in creation. As if to accompany her lush décor, she cultivated an extravagant persona, especially through her clothing. Her contemporaries found the performance at once irresistible and risible. The poet and writer Siegfried Sassoon, visiting Garsington in 1916, remarked on Morrell’s “voluminous pale-pink Turkish trousers.” Desmond MacCarthy, the British critic, described one of Morrell’s hats as being “like a crimson tea cosy trimmed with hedgehogs.”

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

On the last morning of his life, Shinzo Abe arrived in the Japanese city of Nara, famous for its ancient pagodas and sacred deer. His destination was more prosaic: a broad urban intersection across from the city’s main train station, where he would be giving a speech to endorse a lawmaker running for reelection to the National Diet, Japan’s parliament. Abe had retired two years earlier, but because he was Japan’s longest-serving prime minister, his name carried enormous weight. The date was July 8, 2022.

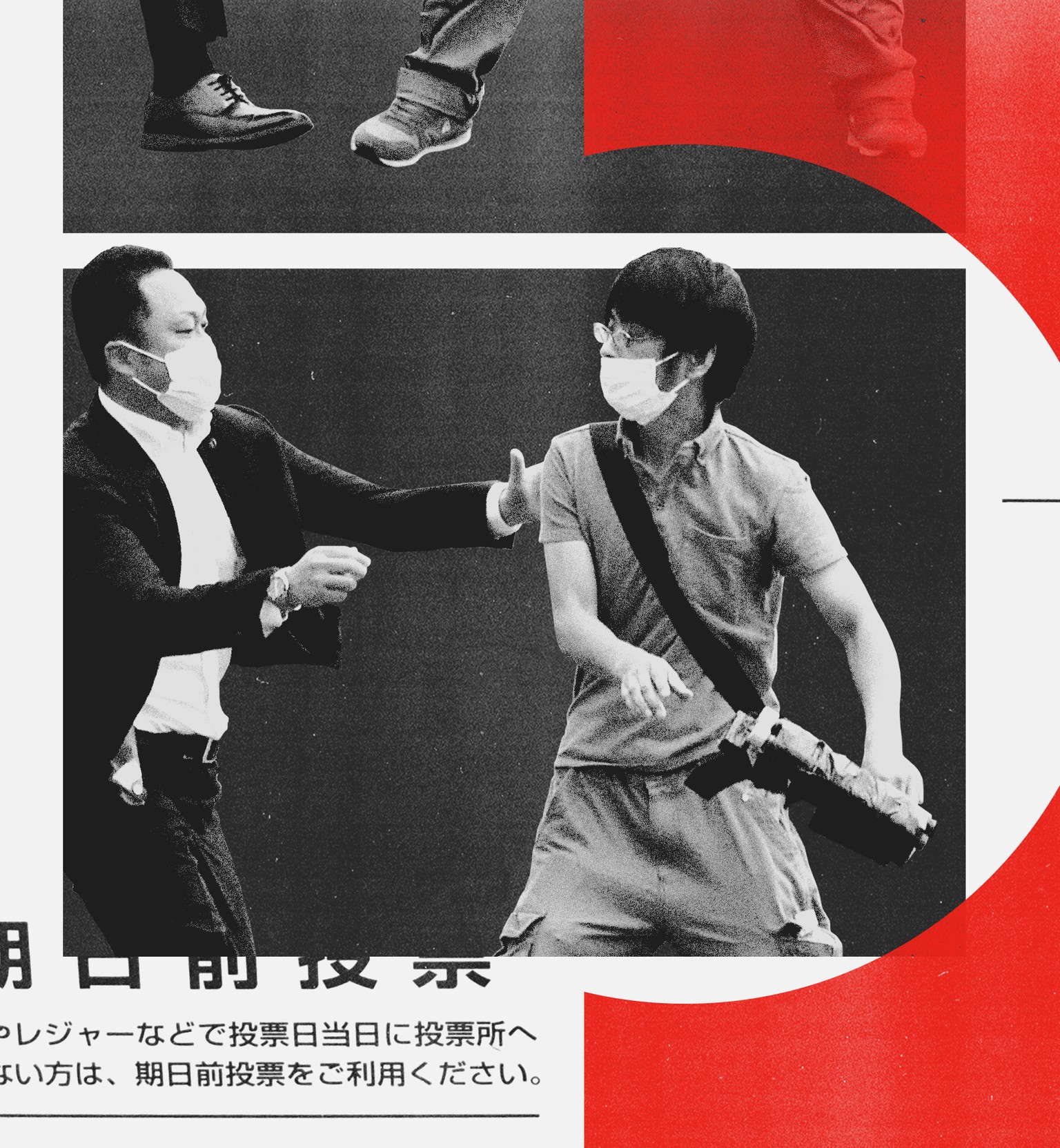

In photos taken from the crowd, Abe—instantly recognizable by his wavy, swept-back hair; charcoal eyebrows; and folksy grin—can be seen stepping onto a makeshift podium at about 11:30 a.m., one hand clutching a microphone. A claque of supporters surrounds him. No one in the photos seems to notice the youngish-looking man about 20 feet behind Abe, dressed in a gray polo shirt and cargo pants, a black strap across his shoulder. Unlike everyone else, the man is not clapping.

Abe started to speak. Moments later, his remarks were interrupted by two loud reports, followed by a burst of white smoke. He collapsed to the ground. His security guards ran toward the man in the gray polo shirt, who held a homemade gun—two 16-inch metal pipes strapped together with black duct tape. The man made no effort to flee. The guards tackled him, sending his gun skittering across the pavement. Abe, shot in the neck, would be dead within hours.

At a Nara police station, the suspect—a 41-year-old named Tetsuya Yamagami—admitted to the shooting barely 30 minutes after pulling the trigger. He then offered a motive that sounded too outlandish to be true: He saw Abe as an ally of the Unification Church, a group better known as the Moonies—the cult founded in the 1950s by the Korean evangelist Reverend Sun Myung Moon. Yamagami said his life had been ruined when his mother gave the church all of the family’s money, leaving him and his siblings so poor that they often didn’t have enough to eat. His brother had committed suicide, and he himself had tried to.

“My prime target was the Unification Church’s top official, Hak Ja Han, not Abe,” he told the police, according to an account published in January in a newspaper called The Asahi Shimbun. He could not get to Han—Moon’s widow—so he shot Abe, who was “deeply connected” to the church, Yamagami said, just as Abe’s grandfather, also a prime minister and renowned political figure in Japan, had been.

Read the rest of this article at: The Atlantic

Actress, style icon, wild-swimming enthusiast, fledgling producer and director in the making: Saoirse Ronan is nothing if not versatile. The protean performer, who has captivated viewers on both screen and stage, talks to Charlotte Brook about taking pride in her Irish roots, navigating life in the public eye and why she still has big ambitions to fulfil

Saoirse Ronan is trying to persuade me that making yourself cry in front of a camera is “a joy”. As ever with the actress, she’s very convincing. “Any pent-up sadness, anger and frustration that you inevitably carry around with you gets let out,” she continues in her still-strong Irish brogue, pushing her white-blonde bob into a scruffy side parting. “So, ironically, it’s the best thing ever.”

Read the rest of this article at: Harper’s Bazaar

One word has been popping up increasingly on earnings calls and in corporate filings of some of the world’s biggest companies. From Wall Street giants like BlackRock Inc. to consumer titans like Coca-Cola Co. and Tesla Inc. and industrial mainstays like 3M Co., S&P 500 chief executives and their lieutenants have used the word “geopolitics” almost 12,000 times in 2023, or almost three times as much as they did just two years ago.

It’s not just talk. Hard evidence is now emerging that all the discussions of strained international relations and more than a decade of warnings over the end of an era of globalization are finally spurring corporations to pick sides with their capital. Western multinationals that for years have avoided geopolitics in favor of pursuing profits in less mature markets are increasingly building the factories of the future in like-minded nations.

As the world’s leaders gather in New York this week for the annual United Nations General Assembly, a Bloomberg Economics analysis of UN foreign-direct investment data points to a world reorganizing into rival — though still linked — blocs that reflect UN votes on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Of the $1.2 trillion in greenfield FDI invested in 2022, close to $180 billion shifted across geopolitical blocs from countries that declined to condemn Russia’s invasion to those that did, the analysis found.

“This is a historic change,” said Yeo Han-koo, a former South Korean trade minister, who sees a world entering an era of upheaval. “A new economic order is being formulated and that will cause uncertainty and unpredictability.”

The accelerants for the shift are obvious. Pandemic-scarred governments are pressing companies to keep national interests in mind and providing subsidies and other incentives as a carrot to bring production home. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and a building US-China rivalry have hastened the end of a fragile post-Cold War model that saw trade and globalization boom.

So too are the potential costs and consequences that are worrying policymakers. In unusually direct language, European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde declared earlier this year that “we are witnessing a fragmentation of the global economy into competing blocs, with each bloc trying to pull as much of the rest of the world closer to its respective strategic interests and shared values.”

Read the rest of this article at: Bloomberg

She comes winging in from behind us, looming into our field of vision, seeming almost too massive to be airborne. She is a white-tailed eagle, one of a species of sea eagles. Haliaeetus albicilla is a close cousin of the North American bald eagle, with its same dour expression, outsized muppety beak, and slightly ramshackle habit of motion, landing like a winter coat falling off a hook. The wingspan of a big female can reach 2.5 meters. These are mythically big animals. Their size makes them bold. They lack the furtive elegance of so many other wild animals. They look casual, like they own the place.

The place owned by this particular eagle is the Isle of Mull, a rugged island off the west coast of Scotland. I am sitting in a truck, parked near a small copse of spruce. Next to me, with a scope mounted on his windowsill, is Dave Sexton from the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, who has studied and protected eagles on and off on Mull since the 1980s. As we watch the eagle approach her nest, we see that she carries a twig in her yellow dinosaur talons. Sexton explains that this pair lost their chick a few weeks ago when a spell of cold and wet weather happened to hit the island just after hatching. With their nestling dead, the couple seem lost. Although white-tailed eagles almost never lay a second clutch, the pair add sticks to their already built nest, perhaps compelled to do so by the stimulus of it being empty.

This pair of eagles have raised several chicks in years past. A local sheep farmer named Jamie Maclean had complained that they were raising their chicks on a steady diet of his newborn lambs, which are born in spring, just as chicks hatch. And so, with Sexton’s help, the Scottish government agreed to pay for some “diversionary feeding.” Maclean would buy fish from a local fishmonger—at retail prices—with government money, and then put them out for the eagles to eat. The idea was that with the free fish rolling in, they’d leave the lambs alone.

“So you can’t quite see it,” Sexton says, pointing out the window of the truck. “But just on the other side of that trailer, up on the hill, there’s a very prominent mound in the middle of a field.” It is here that the farmer offers up his fish.

“You realize this sounds like some sort of Iron Age ritual?” I ask.

“It does a bit,” he says, chuckling.

Sexton believes that eagles take far fewer lambs than other birds, such as hooded crows, ravens, and black-backed gulls. But he still thinks the diversionary feeding program is worth the expense—even if it is mostly a gesture of goodwill. “If I can do something like help with the diversionary feeding … the fact that the eagles are taking fish and not hanging around the lambs, that’s a good thing.”

I am planning to meet with Maclean. I am curious to know how he feels about this pair, after feeding them for years and watching them raise several generations of chicks. I wonder if their intimacy has made him feel any warmth toward them, despite their predatory interest in his lambs.

Read the rest of this article at: Hakai