The end of 2020 was drawing near, and Andrea Turley, a 36-year-old self-employed hairdresser, had to figure out how to afford gifts not only for her two daughters’ birthdays but also for Christmas. She came up with a solution: a job working on the floor of Tesla’s auto manufacturing facility in Fremont, California. It paid about $20 an hour.

Turley’s grandparents had worked at the same plant when it made cars for General Motors. She knew what working on an assembly line would entail and hoped to stay; her grandparents had worked there for decades. “I don’t have a problem with doing hard labor,” she told me.

“The problem was the sexual harassment. It was the racism,” she said. “It’s the constant disrespect.”

On her second day of training, Turley noticed the phrase “Black bitches need to go home” written on the bathroom walls. Once she started working on the line, she heard her white male lead—the person who supervised her on the floor—use the N-word and other racial slurs like “coon,” according to a legal complaint she filed later. He also frequently used the words “bitch” and “cunt.” He “used just about every awful and offensive word I can think of,” Turley said in the filing. It wasn’t just him; other white coworkers also often used the N-word around her and her fellow Black coworkers. She frequently saw the word “bitch” written on the bathroom walls alongside the N-word and “KKK.”

Turley likes to wear layers, dressing like a “tomboy,” she said. Her lead and another coworker started making comments about her being gay, harassing her for her appearance.

Turley had never experienced anything like it at a workplace before. “Never,” she said. In her filing, she wrote: “Every day that I had to show up to work was difficult for me; it was hard to walk into the factory knowing the treatment that I was going to face.” In late December 2020, she sent Tesla’s human resources department a complaint laying out her lead’s racial and sexual harassment. The company didn’t address the issue, she said.

Read the rest of this article at: The Nation

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez was in a car talking with her staffers about legislation and casually scrolling through her X mentions when she saw the photo. It was the end of February, and after spending most of the week in D.C., she was looking forward to flying down to Orlando to see her mom after a work event. But everything left her mind once she saw the picture: a digitally altered image of someone forcing her to put her mouth on their genitals. Adrenaline coursed through her, and her first thought was “I need to get this off my screen.” She closed out of it, shaken.

“There’s a shock to seeing images of yourself that someone could think are real,” the congresswoman tells me. It’s a few days after she saw the disturbing deepfake, and we’re waiting for our food in a corner booth of a retro-style diner in Queens, New York, near her neighborhood. She’s friendly and animated throughout our conversation, maintaining eye contact and passionately responding to my questions. When she tells me this story, though, she slows down, takes more pauses and plays with the delicate rings on her right hand. “As a survivor of physical sexual assault, it adds a level of dysregulation,” she says. “It resurfaces trauma, while I’m trying to — in the middle of a fucking meeting.”

The violent picture stayed in Ocasio-Cortez’s head all day.

“There are certain images that don’t leave a person, they can’t leave a person,” she says. “It’s not a question of mental strength or fortitude — this is about neuroscience and our biology.” She tells me about scientific reports she’s read about how it’s difficult for our brains to separate visceral images on a phone from reality, even if we know they are fake. “It’s not as imaginary as people want to make it seem. It has real, real effects not just on the people that are victimized by it, but on the people who see it and consume it.”

“And once you’ve seen it, you’ve seen it,” Ocasio-Cortez says. “It parallels the same exact intention of physical rape and sexual assault, [which] is about power, domination, and humiliation. Deepfakes are absolutely a way of digitizing violent humiliation against other people.”

She hadn’t publicly announced it yet, but she tells me about a new piece of legislation she’s working on to end nonconsensual, sexually explicit deepfakes. Throughout our lunch, she keeps coming back to it — something real and concrete she could do so this doesn’t happen to anyone else.

Deepfake porn is just one way artificial intelligence makes abuse easier, and the technology is getting better every day. From the moment AOC won her primary in 2018, she’s dealt with fake and manipulated images, whether through the use of Photoshop or generative AI. There are photos out there of her wearing swastikas; there are videos in which her voice has been cloned to say things she didn’t say. Someone created an image of a fake tweet to make it look like Ocasio-Cortez was complaining that all of her shoes had been stolen during the Jan. 6 insurrection. For months, people asked her about her lost shoes. These examples are in addition to countless fake nudes or sexually explicit images of her that can be found online, particularly on X.

Read the rest of this article at: Rolling Stone

My friend Guillaume is always telling me interesting things. Like: there’s a dance called the Madison that many French people think is a regular feature of parties in the United States. Guillaume recently alerted me that a man who was fired for not being fun enough at work got his job back, winning five hundred thousand euros in a landmark case. Last summer, I went to dinner at Guillaume’s, and he mentioned a restaurant, an all-you-can-eat buffet not far from his home town in the South of France. He had just celebrated his birthday there. There was talk of flaming duck and a chocolate fountain. Guillaume showed me a picture of the crystal-curtained lobster tower—seven layers of vermillion crustaceans, topped by an upright specimen thrusting its claws to the sky, as though it had just slayed a halftime show, amid a cloud of mist.

The restaurant is called Les Grands Buffets. A week or so later, I went to its Web site, and entered my e-mail address to receive a secure link to make a reservation online. It was late July. The next available table was for a Wednesday in December, at 8:45 p.m. “We remind you that this reservation is non-modifiable, you cannot change the number of guests, the date of the meal, the hour of the meal, or the name of the beneficiary,” the confirmation e-mail read. If I wanted to bring children under ten years of age, I needed to submit their names at least three days in advance. (They eat at discounted rates.) I would be refused entry if I showed up in sweatpants, an undershirt, a bathing suit, a sports jersey, flip-flops, a ball cap, or any of three kinds of shorts. The toughest reservation in France, it turns out, is not at a Michelin-starred destination like Mirazur or Septime. It’s at an all-you-can-eat buffet situated in a municipal rec center in the smallish city of Narbonne.

Read the rest of this article at: The New Yorker

In late August of 2018, Patriarch Kirill, the leader of the Russian Orthodox Church, flew from Moscow to Istanbul on an urgent mission. He brought with him an entourage—a dozen clerics, diplomats, and bodyguards—that made its way in a convoy to the Phanar, the Orthodox world’s equivalent of the Vatican, housed in a complex of buildings just off the Golden Horn waterway, on Istanbul’s European side.

Kirill was on his way to meet Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew, the archbishop of Constantinople and the most senior figure in the Orthodox Christian world. Kirill had heard that Bartholomew was preparing to cut Moscow’s ancient religious ties to Ukraine by recognizing a new and independent Orthodox Church in Kyiv. For Kirill and his de facto boss, Russian President Vladimir Putin, this posed an almost existential threat. Ukraine and its monasteries are the birthplace of the Russian Orthodox Church; both nations trace their spiritual and national origins to the Kyiv-based kingdom that was converted from paganism to Christianity about 1,000 years ago. If the Church in Ukraine succeeded in breaking away from the Russian Church, it would seriously weaken efforts to maintain what Putin has called a “Russian world” of influence in the old Soviet sphere. And the decision was in the hands of Bartholomew, the sole figure with the canonical authority to issue a “tomos of autocephaly” and thereby bless Ukraine’s declaration of religious independence.

When Kirill arrived outside the Phanar, a crowd of Ukrainian protesters had already gathered around the compound’s beige stone walls. Kirill’s support for Russia’s brutal behavior—the 2014 annexation of Crimea and the bloody proxy war in eastern Ukraine—had made him a hated figure, and had helped boost support in Kyiv for an independent Church.

Kirill and his men cleared a path and ascended the marble steps. Black-clad priests led them to Bartholomew, who was waiting in a wood-paneled throne room. The two white-bearded patriarchs both wore formal robes and headdresses, but they cut strikingly different figures. Bartholomew, then 78, was all in black, a round-shouldered man with a ruddy face and a humble demeanor; Kirill, 71, looked austere and reserved, his head draped regally in an embroidered white koukoulion with a small golden cross at the top.

The tone of the meeting was set just after the two sides sat down at a table laden with sweets and beverages. Kirill reached for a glass of mineral water, but before he could take a drink, one of his bodyguards snatched the glass from his hand, put it aside, and brought out a plastic bottle of water from his bag. “As if we would try to poison the patriarch of Moscow,” I was told by Archbishop Elpidophoros, one of the Phanar’s senior clerics. The two sides disagreed on a wide range of issues, but when they reached the meeting’s real subject—Ukraine—the mood shifted from chilly politeness to open hostility. Bartholomew recited a list of grievances, all but accusing Kirill of trying to displace him and become the new arbiter of the Orthodox faith.

Read the rest of this article at: The Atlantic

In the early aughts, Frank Warren ran a medical document delivery business in Germantown, Maryland. It was a monotonous job, involving daily trips to government offices to copy thousands of pages of journal articles for pharmaceutical companies, law firms, and non-profits. By his early forties, he had a house in a nice subdivision, a wife, a young daughter, and a dog. His family fostered children for a few weeks or months, and he felt a sense of purpose in helping kids who were suffering acute crises in their own homes. From the outside, things appeared to be going better than well. But inside, something was missing: A sense of adventure, or at least a little fun. An outlet to explore the weirder, darker, and more imaginative parts of his interior world. He’d never been one for small talk, preferring instead to launch into deep discussions, even with people he barely knew. He wondered if he could create a place like that outside of everyday conversation, a place full of awe, anguish, and urgency.

In the fall of 2004, Frank came up with an idea for a project. After he finished delivering documents for the day, he’d drive through the darkened streets of Washington, D.C., with stacks of self-addressed postcards—three thousand in total. At metro stops, he’d approach strangers. “Hi,” he’d say. “I’m Frank. And I collect secrets.” Some people shrugged him off, or told him they didn’t have any secrets. Surely, Frank thought, those people had the best ones. Others were amused, or intrigued. They took cards and, following instructions he’d left next to the address, decorated them, wrote down secrets they’d never told anyone before, and mailed them back to Frank. All the secrets were anonymous.

Initially, Frank received about one hundred postcards back. They told stories of infidelity, longing, abuse. Some were erotic. Some were funny. He displayed them at a local art exhibition and included an anonymous secret of his own. After the exhibition ended, though, the postcards kept coming. By 2024, Frank would have more than a million.

*

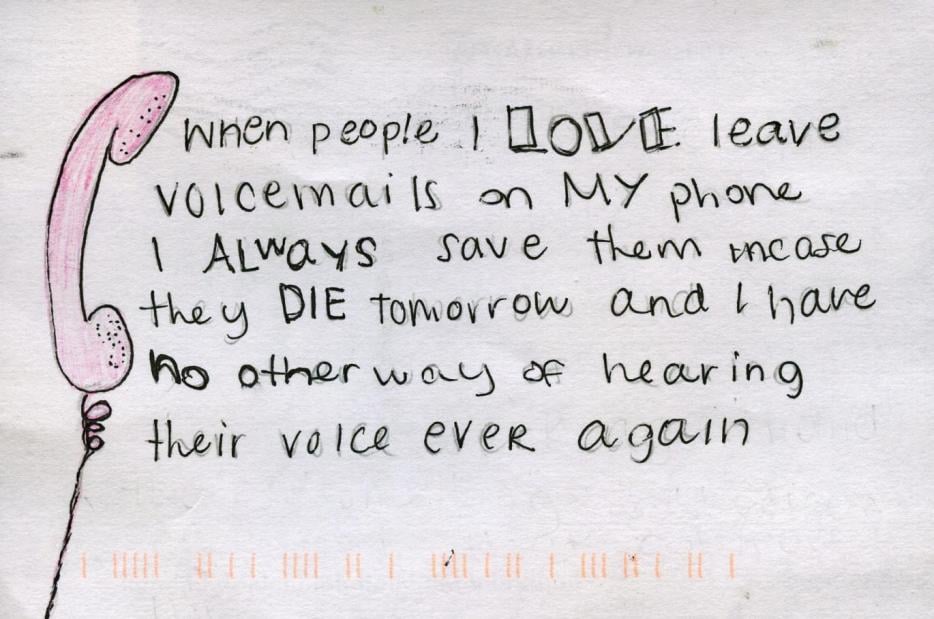

After his exhibit closed, the postcards took over Frank’s life. Hundreds poured into his mailbox, week after week. He decided to create a website, PostSecret, where every Sunday he uploaded images of postcards he’d received in the mail.

The website is a simple, ad-free blog with a black background, the 4×6 rectangular confessions emerging from the darkness like faces illuminated around a campfire. Frank is careful to keep himself out of the project—he thinks of the anonymous postcard writers as the project’s authors—so there’s no commentary. Yet curation is what makes PostSecret art. There’s a dream logic to the postcards’ sequence, like walking through a surrealist painting, from light to dark to absurd to profound.

I’m afraid that one day, we’ll find out TOMS are made by a bunch of slave kids!

I am a man. After an injury my hormones got screwed up and my breasts started to grow. I can’t tell anyone this but: I really like having tits.

I’m in love with a murderer… but I’ve never felt safer in anyone else’s arms.

I cannot relax in my bathtub because I have an irrational fear that it’s going to fall through the floor.

Read the rest of this article at: Hazlitt